Apples & India

From temperate to tropical, exotic to everyday

by Priya Mani

For centuries apples have played a part in Indian cuisine. This journal article was written for Apples & People by Copenhagen-based designer and cultural researcher Priya Mani, who explains the fascinating history of the apple in Indian cookery.

We are delighted to bring you ‘Sēb’, a short book (PDF) of Indian Recipes to cook using apples that Priya Mani has written specially for Apples & People.

(If you are already a subscriber, you have already been sent an email with the link.)

Apples have an unusual virtue in India – they are one of the most expensive fruits to buy, available everywhere through the year, yet exclusive. Ironically, despite India being ranked fifth in global apple production in 2020, producing 2.7 million tonnes, most Indians have never seen an apple tree. To them, its floral notes and characteristic crunch are unknown and the crisp pulp, burst of sweet flavours, and dewy juiciness is elusive. Many generations of Indians, who never grew up near apple trees, just ate old – really old – apples. They were beautiful, red, and shiny with wax but this priciest of fruits were mealy, soft, and simply flavourless. At their high retail price, apples have come to mean hospitality and are perceived as a generous gift.

In most parts of North India, the apple is called seb, from Persian sēb. They are called safarjan in Gujarati, safarchand in Marathi and seema regu in Telugu (safar, seema for travel), as they keep well for travel. Elsewhere in India, they are simply called apple, with a thick local accent. From a culinary perspective, apples boldly flavour curries, are fermented and distilled to make unique beverages and the sweet mealiness of old apples is embraced in classic Indian sweets.

In the foothills of the Himalayas, the temperate valleys of Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh are rich in native apple varieties like kashur farash, maharaji, shireen dahan and ambri. “Ambri seb is our pride! Just try keeping one freshly plucked Ambri at home. You will mark the fragrance, an intense floral aroma fills the air in the cool September weeks.”, remarked a Jammu native I spoke to. Ambri has a high sugar content and a flowery aroma, but poor shelf life keeps its commercial value low. Although indigenous apples are in high demand locally between September and December, markets are saturated with imported commercial varieties like Golden Delicious and Red Delicious.

Much of India’s apple crop is grown in this region and the Kashmiri town of Sopore becomes the epicentre for the region’s apple trade in autumn. Apples are harvested and preserved for winter as harsh weather often cuts off the region from India’s arterial highways.

Clockwise: In Ladakh, seb shirchay, crumbled apple flour on warm barley tea, wild apple extract as a yogurt starter among the pastoral tribes, khushi phey kholak, roasted barley flour gathered with yak butter and apple flour, garlands of dried apple slices sold as tchoonth hache in Jammu & Kashmir, stewed apple stuffed parathas. Apples are batter-fried to make crispy tchoonth pakora, while the mildly sour Maharaji apple is ideal for chutneys and pickles.

Sun drying is an essential culinary technique in the region, locally known as hokh syun. Apples, sliced or diced, spread in the lingering autumnal sun, shrivel, and curl delicately on wicker trays to make tchoont hache, a type of hokh syun. They are sold as long garlands in the local markets. They are tossed into stir-fries and gravies during winter, lending body, and fruity sweetness. Slow-cooked apples and deep-fried aubergines are sprinkled with ver, the region’s spice blend, to make tchoonth wangan. Kashmiri Hindus believe quince and apples are rare things unavailable in heaven, hence an ancestral offering of tchoonth wangan is essential at funerals and memorial services. Parathas are a staple bread and are stuffed with grated and cooked apples. Apples are batter-fried to make crispy tchoonth pakora, while the mildly sour Maharaji is ideal for chutneys and pickles.

Although cooked as a fruit, it is interesting to note that apples don’t feature in the Jammu and Kashmir region’s rich baking tradition. Much of the harvest is sold as fresh fruit and the region has historically had little fruit processing capacity. In Ladakh, where apples are called khushu, there are many native varieties like kerkechoo, bong, khara, mar, mangol, phamer, squirmo and tha. A simple dish from here is khushi phey kholak, where apple flour and roasted barley flour are kneaded and shaped by pressing in the fist to make small balls. It is served at festivals, particularly to mark a child’s first birthday.

India’s early apples

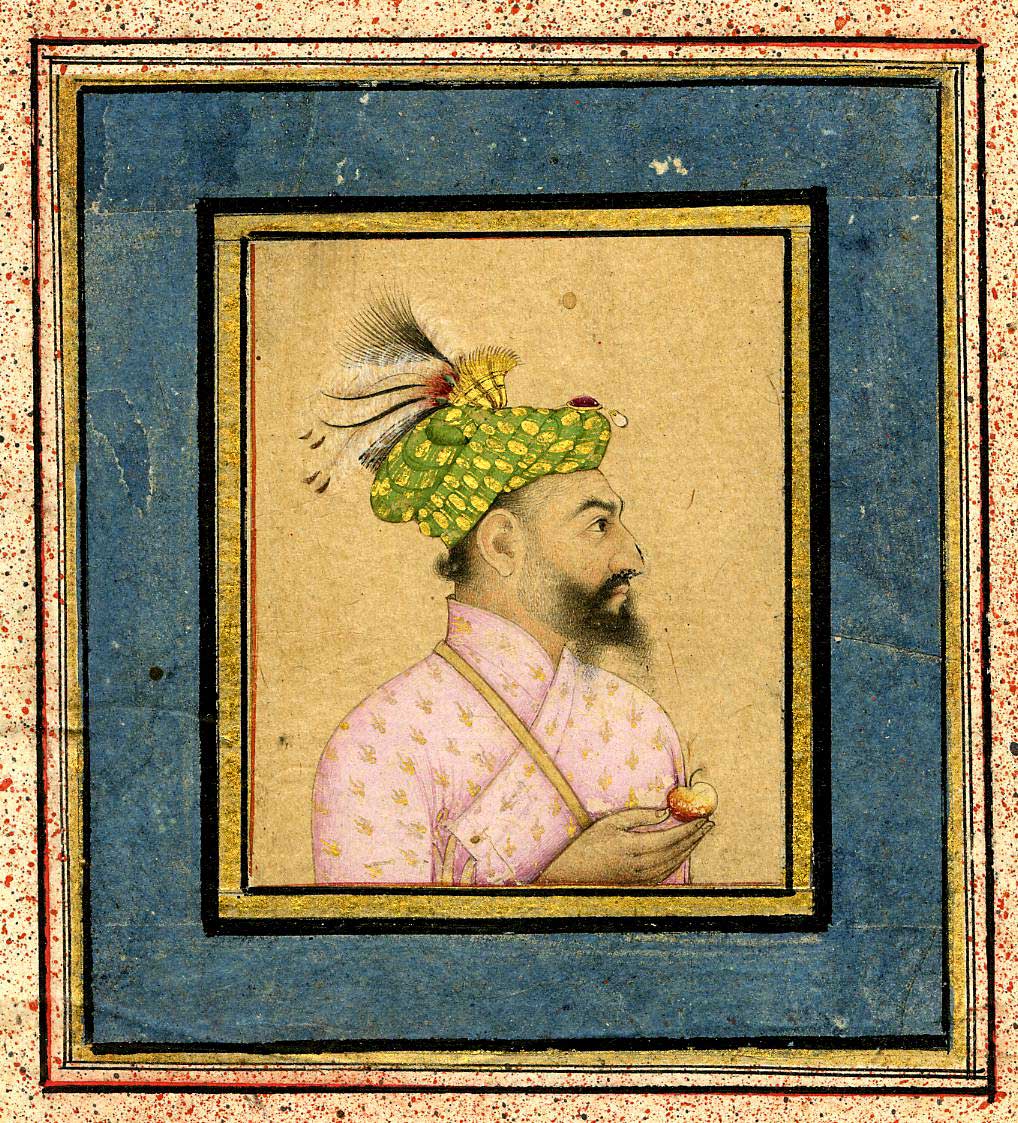

Many varieties of apples have been introduced in India over the last 900 years. Records of early propagation in orchards come from Muslim rulers in the 1300s, then later the Mughals patronized horticulture and grafted apples with many local and Central Asian rosaceous varieties. Ẕiyāʾ al-Dīn Baranī, in his edific Tārīkh-e Fīrūz Shāhī, described the gardens of the Delhi Sultanate under Firoz Shah Tughlaq, who encouraged apple orchards throughout Delhi neighbourhoods from 1309 to 1388, working hard on improving sources of water supply and irrigation facilities in Delhi and surrounding areas.

Apples feature in rather unusual recipes in the Persian manuscript Nuskha-e-Shahjahani, [1628-1658], a collection of recipes from the royal kitchens of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. Two dishes, shisranga seb chashnidar and shisranga seb namky, feature local apples as a prominent ingredient, stewed and served with cracked eggs.

Apple production in the State of Himachal Pradesh, just to the south of the Kashmir region, is India’s most efficient and fruits are sold in domestic and international markets. With the abundance of produce, the fruit has been assimilated into local culinary traditions. In Spiti, where there is a rich tradition of fruit-based fermented and alcoholic beverages, apples are used with barley and sometimes wild apricots to brew ara or ark, a light honey-coloured tipple.

In Kinnaur, apple and apricot must is fermented and distilled to make ghanti, a clear, smooth spirit, enjoyed neat. Festivals, weddings and carnivals bring the village together and rak is the occasion’s top tipple. Dried apples, apricots and pear are mixed with barley and jaggery to make this fruity, fermented beverage. Rak, called phasur or raakt in Kinnaur area, uses phab, a traditional inoculum of lactic acid bacteria and moulds. These and other fermentation starters like kheem or dehli are made of dozens of medicinal plants and herbs, foraged, crushed, rolled into tight balls and sun dried. To use, they are crushed and evenly rubbed over cooked grain like barley and chopped fruits and allowed to ferment. The horticulture industry today has large post processing facilities to make jams, jellies, apple cider, vinegar and juice.

Apples have been crucial to the transformation of Himachal’s hillscape and her people. In her book, “Blossoms in the Dust: The human factor in Indian development” (1961), Kusum Nair writes, “In one instance where I came across a transformation in the economy and way of life of a people, the primary cause (if any single factor can ever bring about a socio-economic revolution of any substance) was not education – but apples. Education has followed apples. It did not precede them.” She poignantly notes that 94% of this State’s population is dependent on the 3000 acres of apple horticulture at the time. This transformation was possible by the efforts of Samuel Evans Stokes, a young American, who arrived in Kotgarh as an American missionary in 1904.

Before long, he was deeply engaged with the local people and their social progress. He established the Harmony Hall orchard at Barobagh, converted to Hinduism calling himself Satyanand Stokes and married a local Christian tribal girl called Agnes. Stokes’ humanistic approach in establishing commercial orchards has had a lasting effect on Kotgarh and Himachal at large, spurring the formation of a well-supported horticultural and fruit processing industry today. He is widely regarded as the man who catapulted the apple orchard to a meaningful commercial path. At Stokes’ Harmony Hill orchard, his grandson Vijay Stokes has introduced resilient horticultural practices partnering with global institutions to seed their knowledge in the region’s orchards. Vijay acknowledges tradition, but his empirical approach to horticulture is imperative for responsible farming with a priority on community development.

Apples in India’s wider culinary landscape

Apple cultivation has been rarer in the rest of India until now, with only a few ideal microclimates like the higher altitudes of the Deccan plateau and montane slopes in Nilgiris in the south. Indigenous Himachal and Kashmir produce make a rare appearance in the markets of far-flung southern cities.

“Maharashtrian Lady with Fruit”, Raja Ravi Verma, undated. [estimated, 1870-1900]. Image courtesy: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation, Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kowdiar Palace. A noble lady from Maharashtra region holds a platter of fruits typical of an Indian winter – oranges and grapes, native to the region; and apples, perhaps brought from Deccan or Kashmir, an exotic fruit, nonetheless.

Most of the apples sold locally remain apples from New Zealand and Australia. This well-established trade of imported apples, first established by British colonial officers and a flourishing activity since, has ensured a year-long availability, making them familiar, ubiquitous, yet expensive.

Apples, sorely missed by colonial expats in the British Indian Presidencies, were imported from New Zealand, while canned apples arrived from America. In 1878, Colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert “Wyvern”, noted in his Culinary Jottings for Madras “…apples make delicious fritters; … For these we must look to the tin; those that come to us from America are specially to be recommended.”

Wyvern, stationed at the Madras Presidency, followed up his book’s success with another, “Sweet Dishes“, with mostly recipes tailored for British expats and local elites. He uses both fresh and canned apples to make apple chartreuse, apple cheesecake, apple tart, timbale de brioche aux fruits, apple dumplings and apple snow, noting that they taste particularly good with canned apples. Wyvern notes a recipe for the immensely popular Madras Club Pudding, a boiled bread pudding with canned apples served with Sauce Royale. The Madras Club serves a version of this as Bread Pudding even today. Among other notable writers, R Riddell in his Indian domestic economy and receipt book (1860) and Daniel Santiago in The Curry Cook’s Assistant or, Curries, How to Make Them in England in Their Original Style, (1887) include recipes for apple sauce, mincemeat and mulligatawny soups using apples. The yearning for apples and its limited availability also led writers to offer recipes like mock apple sauce with pawpaw.

From left: Some recipes from Wyvern’s Sweet Dishes: Apple fritters, apple snow, whipped cream folded with stewed apples, Madras Club Pudding served with Sauce Royale, apple sauce and mock apple sauce with pawpaw. Mulligatawny soup recipes from the period feature apples prominently, apple dumplings and canned apples imported from America. © Priya Mani

Colonial horticultural efforts were clearly in their early days, for even thirty years after Wyvern, in 1909, Flora Annie Steel had different advice, guiding the readers of her The Complete Indian housekeeper & Cook to bring apple rings from home (England), and noting “the Californian-dried fruits are extremely useful, and infinitely preferable to those in tins”.

Apples, both imported and local, have taken on local flavours in India’s diverse Muslim kitchens. In the Hyderabad region, grated apples are made into seb ka meetha, where they are cooked in a simple syrup and spiced with cardamom, saffron and, sometimes, a dab of screw pine essence. Apples, pounded into fine bits, are cooked and blended with ghee and sugar to make Seb ka zarda and topped with fried cashews and almond slivers. Whole apples are stewed and stored in sugar syrup to make Seb ka murrabba. Chopped apples and bananas blend seamlessly into the soft velvety folds of a fruit custard made the Indian way.

Clockwise: Seb aur badam ka shorba, seb ka halwa, apples in a fruit custard, fruit leather, fruit chaat, seb ka kheer, apple pickle, seb ka meetha, seb cirki or apple cider vinegar and seb ka murrabba © Priya Mani

In the northern states, apples take on a savoury flair, too. They are cooked with almond paste to make seb aur badam ka shorba, India’s version of ajo blanco. The soup is seasoned with ginger, white pepper, caraway seeds and honey. It is served warm with a dollop of whipped cream. Apple is the star of fruit chaat, now a pan-India preparation, where together with pomegranate, bananas, guava, it is tossed with chaat masala – a blend of dried mango powder {amchur}, black rock salt {kala namak}and a hint of cumin and coriander and a generous squeeze of lime juice. Diced apples are pickled in mustard oil with turmeric, chillies, nigella and fennel seeds to make seb ka achaar.

They are also cooked into a classic halwa, scented with saffron and ghee or set into a barfi, a lozenge-shaped fudge of apple pulp. Safarchand papad is a popular fruit leather of pureed and cooked apples. Cooked apples are blended with a reduction of milk in a take on the classic Indian kheer.

Tropical apples are taking India by storm

In 1998, Hariman Sharma, a farmer from Bilaspur in the warmer plains of Himachal Pradesh, threw an eaten apple in his backyard. A few months later, he realized there were apple saplings, and in 2001, they bore fruit. Grafting on a local plum, the yield improved and together with the National Innovation Foundation, Hariman has developed low chilling apples, patented as HRMN-99.

HRMN-99 tropical apples grown in Manipur, a hilly state in North-eastern India with tropical and subtropical weather zones. Summer temperatures can be as high as 40 degrees Celsius. Courtesy of Harman Singh.

He distributes hundreds of saplings throughout India from his orchard in Bilaspur, which has now spurred a wave of tropical apple orchards, meaning more Indians are now seeing apples growing on trees and experiencing the taste of fresh apples.

Tropical apples are bringing a new era in India’s consumption of apples. Convection ovens are becoming more commonplace in Indian homes today, and the tsunami of online food content influences how people are beginning to use apples. Upmarket bakeries have put Western-style apple pies, cheesecakes, strudels, jams and jellies on their menu. Will local varieties drive prices down, and will a nation in the grip of Noma-inspired hyperlocal food ideologies shun imported apples? Well, with tropical apples cultivated across India, at least, a new generation of Indians will learn the taste of a freshly plucked apple – crunchy, sweet and unforgettably juicy.

Further notes:

1. Apple cultivation and processing in the Kashmir region: Horticulture and post processing facilities have become the focus of the present Government in the Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh region for social development. However, terrain and climate change issues remain challenging. Ramneek Kaur, a social activist working with pastoral tribes like Gujjar- Bakharwals notes that many of them lease land to grow apples but their lack of understanding horticultural nuances together with climatic catastrophes yields lower-grade apples or often loss of the entire crop. George Watts in his magnum opus The Economic Products of India (1890) notes, “.. some years ago, the Maharaja of Kashmir made an attempt to start the manufacture of cider in his territory. He obtained the services of a European for the purpose, but the experiment appears to have been unsuccessful.” However, in recent years, Kashmiri apple cider has gained momentum among home grown brands.

2. A brief history of the apple industry in Himachal: On 12th March 1838, a box of four apples arrived at the Secretariat of the Horticultural Society of India. The Secretary noted, “all those who saw and tasted the fruit thought them to be equal in beauty and flavor to any they had tasted in England.” Grown from English grafts, they were planted in 1824 in the garden of Mr Jeffery Finch in Tirhoot, bearing the first fruits in 1836. A decade later, the Treaty of Lahore brought Kullu under British control, frequented by British officers escaping the hot plains. Meanwhile, Rev.Beutel, a German missionary developed the first Kotgarh Mission Orchard. In 1870, Captain R C Lee, a retired British official, set up an apple orchard in Banderole with plants obtained from England and soon many others established orchards in the region, setting an apple industry in motion. In Shimla, the first orchard was planted in 1887 in Mashobra, now owned by the Government and primarily functions as a research center. In 1921, Samuel Evans Stokes obtained a sapling of Golden Delicious from the Stark Brothers Nursery in Louisiana and propagated it at his orchard, Harmony Hall. By 1929, he could market the apples under the “HH Brand” with resounding success. Stokes’ humanistic approach in establishing commercial orchards had a lasting effect on Kotgarh. His approach was sustainable and socially responsible long before these words became a corporate staple.

3. History of Apple cultivation in the Deccan region: The Khazan wa-Babur, a gardening manual from Deccan during the reign of Nizam Ali from 1790 outlines advice on landscaping and growing fruit trees. For bright red apples, the author recommends pegging down the lower branches with an iron bar. By 1860, R Flower Riddell, Surgeon General to the Nizam of Hyderabad wrote in the Indian domestic economy and receipt book, “In the Deccan, I have met with two sorts, like the brown russet, and a yellow striped pippin. These trees only bear but once a year and require the same treatment as the Persian apple.”

Apples grown on the higher altitudes of the Deccan plateau remained available locally – they were small, sour-sweet and certainly lacked the famed charm of Kashmir’s temperate fruit.

4. Apple Cultivation in the Colonial Era: Horticulture became a priority in the colonial agenda and apple cultivation has been written about widely during this period. In 1938, The Punjab Fruit Journal offered recommendations for apple cultivation in commercial orchards in Simla Hills. The author, S. Blake suggests varieties such as Cox’s Orange Pippin, and Peck’s Pleasant for apples that keep a long shelf life from harvest in fall until Christmas and even unto March noting “Varieties such as Lady Sudeley and Red Astrachan are fine table apples but keep for about 6 weeks and should be sold before they lose their crispness and flavour.”

Another chapter in the Journal suggests, “Cleft grafting is used in order to improve or renovate old trees. The tree is headed back to a few limbs in which clefts are made and graft wood from desirable trees inserted into them. The union is covered with grafting wax and the cleft is bandaged.”

Priya Mani is a Copenhagen-based designer and cultural researcher working to create gastronomical experiences. Having studied at the National Institute of Design, and over the past 20 years, she has pursued the craft of culture, through textiles, technology and food. Her particular interest is in the human factor, and has worked for over a decade in the area of design and innovation across industries. She is currently working on a Visual Encyclopaedia of Indian Foods, which won the Guild of Food Writers Award for Food Writing 2022 and nominated by the IACP Award for Food Writing 2022. She is a Trustee of the Oxford Symposium on Food & Cooking.

Sources:

- Angchok, Dorjey (2009) On Foods of Ladakh: Traditional foods and beverages of Ladakh. Indian journal of traditional knowledge. 8. 551-558.

- Delhi Development Authority (2017-2019) Bagh-e-bahaar: Tracing a sense of place for the last surviving Tughlaq Garden in an urban context. District Park, Delhi, India.

- Tsetan Dolker, Deepak Kumar, Joginder S. Chandel, Spalzin Angmo, O.P. Chaurasia and Tsering Stobdan (2021) Phenological and Pomological Characteristics of Native Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) Cultivars of Trans-Himalayan Ladakh, India. Defence Life Science Journal, Vol. 6, No. 1, January 2021, pp. 63-68

- Syed Muhammed Fazlulla (1628-1658) Nuskha-e-shah Jahani. Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras

- Gouri, Sushil Mudgal, Elaine Morrison and James Mayers (2004) Policy influences on forest-based livelihoods in Himachal Pradesh, India.

- Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert (1879) A Treatise … on Reformed Cookery for Anglo-Indian Exiles, Based Upon Modern English, and Continental Principles, with Thirty Menus for Little Dinners Worked Out in Detail, and an Essay on Our Kitchens in India. Higginbotham and Company.

- Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert (1884) Sweet Dishes: A Little Treatise on Confectionery and Entremets Sucrés. Higginbotham and Company.

- Priya Mani A/ Apples, in A Visual Encyclopaedia of Indian Foods

- T S Rana, Bhaskar Datt, R R Rao (2004) Soor: A traditional alcoholic beverage in Tons Valley, Garhwal Himalaya, Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 3(1), January 2004, pp. 59-65

- Ajay Singh Rawat (ed) (1993). Indian Forestry, a Perspective, Indus Publishing, 1993, p. 354

Thanks to:

Patrizia Boglione, who inspired me to collect all these apple recipes into a cookbook, and David & Ann Marshall for patiently editing and testing the recipes.

Many experts have helped me decipher the method to recreate recipes from Nuskha-e-Shahjahani. I reached out to Professor Daniel Newham, Durham University, an expert in translating Persian manuscripts. Newham noted, “a rather odd recipe .. namky refers to salt in the recipe while chashnidar is ‘tasty’, ‘heavily seasoned’ and both recipes are simply entitled ‘pukhtan’ or cooking. In a quest to find a detailed cooking process I reached out to Dr. Simi Rezai, a fellow Symposiast from the Oxford Food Symposium. Dr. Rezai together with Dr. Rahimlou and Ms. Sarvenaz Paknia in Iran has translated the recipe for recreation.

I am also grateful for personal interviews and conversations with Raja Ravi Verma Foundation, Vijay Stokes, Hariman Sharma, Ramneek Kaur of Shepherd Crafts, Burhan ud din Khateeb of Kashmir Innovation Lab, Sapna Bhat, Shobha Paryani, Durga & K S Mani, Bagyalakshmi Subramanian and Mehroosh Tak.

![“Maharashtrian Lady with Fruit”, Raja Ravi Verma, undated. [estimated, 1870-1900]. Image courtesy: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation, Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kowdiar Palace. A noble lady from Maharashtra region holds a platter of fruits typical of an Indian winter – oranges and grapes, native to the region; and apples, perhaps brought from Deccan or Kashmir, an exotic fruit, nonetheless. “Maharashtrian Lady with Fruit”, Raja Ravi Verma, undated. [estimated, 1870-1900]. Image courtesy: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation, Collection: Travancore Royal Family, Kowdiar Palace. A noble lady from Maharashtra region holds a platter of fruits typical of an Indian winter – oranges and grapes, native to the region; and apples, perhaps brought from Deccan or Kashmir, an exotic fruit, nonetheless.](https://applesandpeople.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/07-Raja_Ravi_Varma2.jpg)

M.Legrand – Incubator and Creator of the Michelin

M.Legrand – Incubator and Creator of the Michelin Photograph by Irving Penn - Red Apples, New York (1985) © The Irving Penn Foundation. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles USA, Gift of Nancy and Bruce Berman

Photograph by Irving Penn - Red Apples, New York (1985) © The Irving Penn Foundation. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles USA, Gift of Nancy and Bruce Berman