Kashmiri Apples

A Weapon of Resistance

In the fourth century BC, Alexander the Great trained his navy for war with a mock battle on the Euphrates outside Babylon where crews on ships of the royal fleet pelted each other with apples.

Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, who assumed command of the British fleet on Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, is reported, in a perhaps choreographed signal of nonchalance, to have stood on the poop deck with his back to a mast “munching an apple as the Royal Sovereign bore down majestically upon the enemy line.”

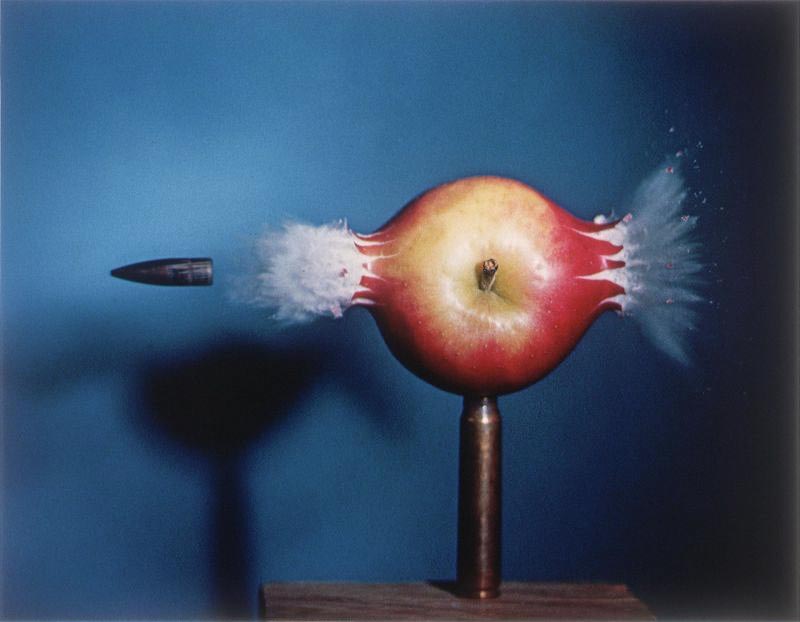

Occasionally, through human history, the benign apple has found itself used as a weapon or a symbol of resistance. This article, which has been written for Apples & People by two Kashmiri academics, considers the weaponization of apple production today in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.

Kashmiri Apples: A Weapon of Resistance

Haris Zargar and Mehroosh Tak

What makes the cultivation of a certain type of crop, tree, or fruit integral of a nation’s political and cultural consciousness – beyond its economic significance – is a million-dollar question. In many regions of the world, certain trees are seen as the symbol of their national identity – be it ceiba tree in the Americas, olive trees in occupied Palestinian territories, or kauri trees in Titirangi (New Zealand).

In Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir, saffron has long been recognised as a high-value crop and crucial marker of the region’s cultural heritage. However, over the past few decades, apples have seemingly become the main embodiment of this restive territory’s economic and political identity. The centrality of apple farming in the Kashmir valley has effectively been interwoven into all aspects of the society, contributing significantly to livelihoods and economic sustenance for the population. Apple cultivation in this fiercely disputed Himalayan territory, therefore, has emerged into an active site of conflict, as well as resistance, against the Indian occupation – akin to olive farming in occupied Palestinian territories.

As Irus Braverman emphasises in her book ‘Planted Flags’, there is a deep connection between trees and land, that are as much cultural as they are physical – implying that the innate relationship between identity and territory cannot be explained merely by material forms such as economy or land but also through the metaphoric constituents to that relation such as trees. Thus, for an occupying state, (re)shaping the physical landscape – ecological as well as agricultural – becomes an intrinsic part of the political project, while for those resisting the occupation, preserving the landscape become a vital component of resistance.

It is in this context that the imagination of an apple tree and economy in Kashmir has taken a pivotal role in the resistance of Kashmiri people as has been the state’s strong intervention to reconfigure this economy. ‘

Horticulture, principally apple farming, is regarded as the backbone of the Jammu & Kashmir’s economy. According to official data, the sector contributes over eight percent to the Gross State Domestic Product of the region. The apple sector – which contributes over £500 million to the local economy annually – alone generates livelihood for over 3.3 million people. The natural topography and cold climate of Kashmir – where almost 75% of apples produced in India are grown – makes it an ideal place for cultivating the fruit, with over 2.6 million tonnes exported annually to the markets in India and abroad.

The area under cultivation of fruits in Jammu & Kashmir increased from 2.21 lakh hectares in 2001 to 3.33 lakh hectares in 2020-21 – registering an increase of 1.22 lakh (122,000) hectares in two decades. This increase in apple cultivation is remarkable given that historically Kashmiri famers were heavily invested in paddy farming. By the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, the Kashmir valley experienced a considerable shift from paddy farming (subsistence) to apple cultivation (cash-crops), as more land – although of small size – became available to marginal farmers because of land redistribution policies implemented in the mid-1970s. The redistribution of land arguably allowed the small and marginal farmers to engage in cash crops such as apple, which in turn increased disposable incomes of households. At the same time, however, the food consumption increasingly relies on importing of food from outside Jammu & Kashmir – a shift also pushed by the state to increase reliance of Jammu & Kashmir on India.

The Indian state is restructuring the apple supply chain by restricting market access, destabilizing pricing, and replacing the traditional cultivation practices including more resilient native apple varieties such as ‘Ambri’ varieties (including Dodhi Ambri, Chari Ambri, Walayati Amberi, Mah Ambri) and crossbreed varieties of ‘Delicious’ varieties (Red Delicious, Golden Delicious), with internationally imported rootstock from Italy. While local Kashmiri farmers and traders occupy the production stage of the supply chain, the Indian contractors and middlemen mostly control the commercial and market end of the sector’s value chain.

In September 2022, a dozen fruit mandis in Kashmir went on strike against the “unnecessary” delay in the movement of trucks on the Srinagar-Jammu highway, which connects the region to India. Fruit growers claimed more than 8,000 trucks were stuck on the highway, quietly rotting the fruit. The army regularly prevents movement of trucks on Kashmir’s main national highway carrying millions of dollars’ worth of apples, leading to devaluation of produce in the market. A small farmer from South Kashmir stressed that the Indian government’s intention was not in favour of the local growers but that the authorities often seem to create impediments for the apple farmers, to dissuade them from continuing apple cultivation.

A key disruption to the apple economy has been the introduction of a high-density rootstock. Currently imported from Italy, the high-density rootstock is from the Malling-Merton series, that originated in NIAB’s East Malling Research Station in the UK. The market for rootstock is unregulated and often not quarantined before being distributed in the region, increasing the risk of disease spread. Farming of high-density apples – which uses dwarf bushes with tight spacing – is capital and labour-intensive, unlike the cross-breed or traditional varieties of apple present in the region. Smallholders thus face income depletion by moving to high investment, high yielding commercialised and intensive farming mechanisms that push them out of the value chain.

In addition, the Indian state’s insistence on higher density farming, as it aims to bring over 5,500 hectares of land under apple farming by 2025, would arguably also necessitate more labour – mostly from outside the region – and utilization of contract farming by leasing out to contractors. This would immensely disrupt the existing relationship between labour and land, as it would transfer this critical mode of production to non-locals, particularly to large agro firms, and deprive locals of their means to livelihood. A Dubai-based Indian corporation for instance has leased over 350 hectares of orchards in Central and South Kashmir areas.

Farmers have been reluctant to embrace new varieties, pointing to disappointing results from pilot projects, and complained that shifting to high-density varieties incurred huge input costs and were very vulnerable to weather and climate changes. Climate crisis has meant early snowfalls in the region have affected farmers because they lose their crops. Critically, the push towards high density rootstock is having ecological impact due to intensification including biodiversity loss of indigenous breeds.

Forced market introduction of high-density rootstock in the region will also arguably lead to further ecological crisis in the region given the high-density varieties require more water for irrigation, more pesticide and fertilisers impacting soil fertility and ground water, and would reshape the valley’s horticulture landscape in which tall green apple trees will be replaced by small apple bushes attached to plastic wires.

It is for these specific reasons that apple farmers and traders have been the only segment of the valley population that have expressed their open resentment to the disruptive changes in the region, where dissent otherwise has been silenced.

Regular disruption to the apple value chain is seen as oppressive and against local farmers’ human right to earn a livelihood. Safeguarding the apple is now arguably synonymous with preserving the Kashmir (cultural, economic, and political) identity – even if not yet explicitly.

This article is based upon long term research conducted in Kashmir in 2021 and 2022 by Mehroosh and Haris. The research is supported by the Independent Social Research Foundation.

Sources:

- Braverman (2009) Planted Flags

- Juniper and Mabberley (2019) The Extraordinary Story of the Apple

- Lane Fox (1973) Alexander the Great

- Murray (1936) The Life of Admiral Collingwood

Contemporary Herbarium of the Orchard and Fruits of the Press By Roselyne Corblin and Pascal Levaillant

Contemporary Herbarium of the Orchard and Fruits of the Press By Roselyne Corblin and Pascal Levaillant Inspiring apples By Students at Central St Martins

Inspiring apples By Students at Central St Martins