Eve and the Apple

How artists have interpreted the forbidden fruit

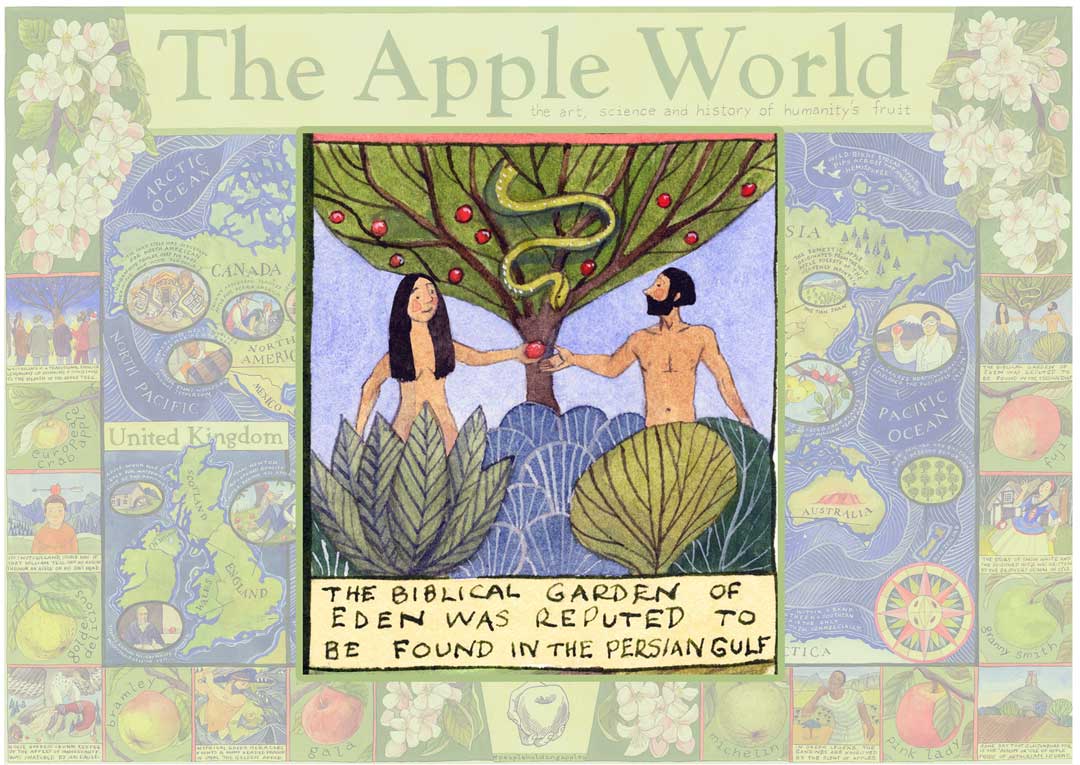

The association of Eve and the apple seems familiar enough, although the variations which artists choose to portray are more varied and nuanced than you might expect. Perhaps this is not surprising as variation is at the root of the original fruit tree, one which carries the dual knowledge of both good and evil.

Many artists are faithful to the original biblical narrative where God states that Adam and Eve are forbidden to eat fruit from the tree of knowledge. Rubens and Brueghel’s Eden is a wooded menagerie where a fleshy spot-lit Adam and Eve are exchanging fruit passed down by a coiling serpent above. This coil of temptation begins with the serpent in the bible who says to Eve:

“Ye shall not surely die: For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”

Genesis 3:4–5

This painting depicts the moment just before Adam bites into the apple as the animals are still in harmony within the landscape. A precursor to the sin about to unfold is symbolically depicted in the form of the Capuchin monkey to the left of Adam, who bites into an apple.

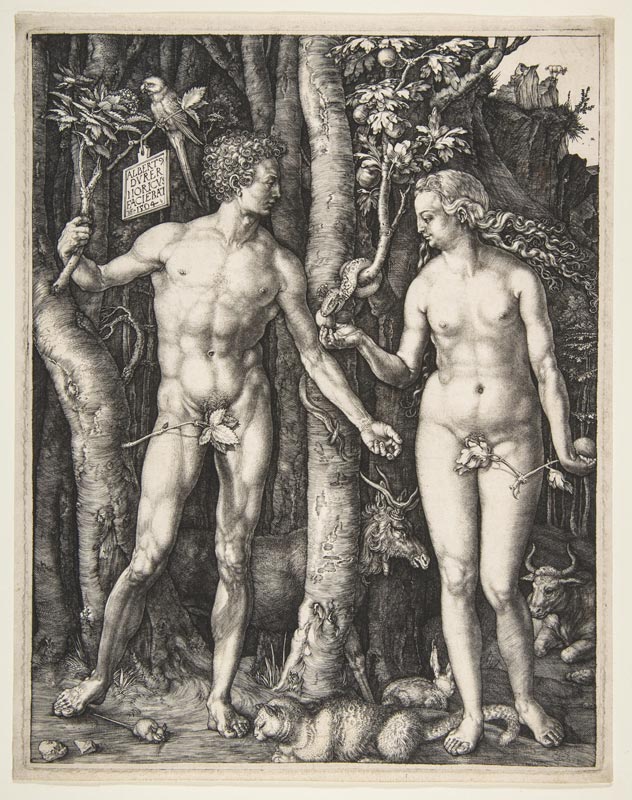

As for the apple, the status of the forbidden fruit in the Bible is often a matter for debate. The fruit has been associated with pomegranates and figs amongst others. In Albrecht Dürer’s 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve, it is thought to be a fig branch which Eve is grasping though it is an apple which she takes from the serpent. The forbidden fruit seems to have widely settled on the domestic sweet apple in European art perhaps owing to a linguistic confusion between two unrelated words mălum, a native Latin noun which means evil (from the adjective malus), and mālum, another Latin noun, borrowed from Greek μῆλον, which means apple. So ‘evil’ and ‘apple’ seem to have been entwined in a symbolic duality which has secured the fruit’s totemic status.

So, what of Eve and her relationship to the apple and how she has been depicted by artists? There is certainly a paradox at work as varying interpretations of the Genesis story centre around Eve and her culpability or innocence. Eve’s mutability flexes between mother earth, temptress, innocent go-between, transgressor and more recently, feminist.

In G.F. Watt’s ‘Eve Tempted’ she has become overwhelmed, intoxicated even, by apple blossom and fruit. So much so, she appears to be almost consumed by the foliage which engulfs her. This work formed part of a trilogy by Watts which depicted the birth of Eve, her temptation, and later, repentance. The idea of a staged trilogy and one ending with Eve’s redemption moved her traditional depiction and characterisation into a new, more considered direction, albeit one which still suggests guilt and the need for repentance.

Yet it is when female artists begin to take on Eve that things really start to be shaken up, or off the apple tree, as established and entrenched Eden narratives are overthrown to give us alternative perspectives.

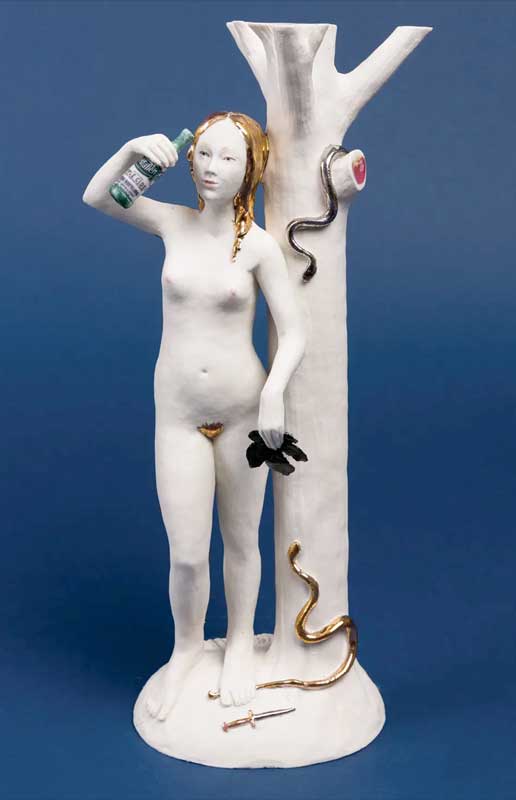

Claire Partington has created a porcelain ‘Drunk Eve’ who stands defiant with a discarded fig leaf, swigging cider instead of eating apples. The serpent has been silenced at her feet.

In Siobhán Hapaska’s playful series of sculptures ‘Snake and Apples’ Eve has been removed altogether. Instead we are left with a snakeskin-clad framework through which oversized apples are balanced and squeezed. There is a ‘snakes and ladders’ feel to the work which suggests a precarious, constrained game – as if the form and narrative of the apple is being continually fed and processed. Here we read the apple as representing humanity’s downfall in a never-ending game of chance with limited outcomes. Equally, as a series of sculptures with both green and red apples the idea of good and evil being at the heart of the fruit (and the tree of knowledge), reinforces the limited binary choice at the fruit’s core. Yet perhaps with no Eve or Adam present we can interpret ‘the fall’ moving away from human nature to that of the snake – the ultimate controller in the game of apples.

Purgatory Plucked

An Apples & People commission by Hilary Norris

A three-minute musical composition by Hilary Norris combining fifteenth and sixteenth century texts about Adam and Eve

Hilary Norris is a musician (organist, harpsichordist, composer, and choral director) and Director of Music at Leominster Priory in Herefordshire. She was commissioned to compose and recorded a musical composition about Adam and Eve that includes setting the fifteenth century rhyming poem ‘Adam lay ybounden’ to music, balancing this with Eve’s perspective.

Hilary explains her creative process:

‘Adam lay ybounden’, which describes the ‘fall’ of man, has been set to music by several composers. Ord’s famous choral setting is sung by choirs all over the world as part of Christmas celebrations. The optimistic text is short, but packed full of meaning and provides an explanation of why the taking of the apple led to the birth of Jesus, the son of Mary (“heaven’s queen”).

“Adam lay ybounden,

Bounden in a bond;

Four thousand winter

Thought he not too long.”

“And all was for an apple,

An apple that he took.

As clerkës finden written

In their book.”

“Ne had the apple taken been,

The apple taken been,

Ne had never Our Lady,

A-been heaven’s queen

Blessed be the time

That apple taken was!

Therefore we may singen

Deo gratias!”

I found a wide range of texts that included Eve’s perspective, including poems and narratives from various centuries. We decided upon the following passage from Tyndale’s 1534 Bible:

“Then sayd the serpent vnto the woman: tush ye shall not dye:

But God doth knowe that whensoever ye shulde eate of it youre eyes shuld be

opened and ye shulde be as God and knowe both good and evell.

And the woman sawe that it was a good tree to eate of and lustie vnto the eyes and a pleasant tre for to make wyse. And toke of the frute of it and ate and gaue vnto hir husband also with her and he ate.”

The two texts are entirely different. ‘ Adam lay ybounden ‘ is a snappy, alliterative, rhyming poem which expresses the celebrations of ordinary people at Christmas, combining many important religious ideas. The Tyndale extract is a wonderfully evocative, sensual and profound prose describing temptation and the fall of mankind from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience.

It was clear that the two texts needed entirely different musical treatment but that one had to lead to the other. The Tyndale extract is therefore set in a way that creates a tension that is released in a folk-like, joyful setting of ‘Adam lay ybounden’.

For the Tyndale verses:

It is hard to describe the process of composition, because you find yourself experimenting with the text and musical ideas in all sorts of ways. After considering the text a great deal, this describes, to some extent, what I did:

Said and sang the words many, many times, and jotted down the speech rhythms several times, until I agreed with myself!

Adapted the speech rhythms so that emphasis and silence, a sense of push and pull/tension and release, would express the words and meaning as clearly as possible.

Spent time improvising on the piano while singing the words to allow the melodies and harmonies to suggest themselves. Worked at a harmonic scheme that would tell the story in waves of increasing tension, each wave leading to the crucial statement in the text (describing the fall) set on unison notes – the truth laid bare.

Recorded the voice part first, so that the natural flow and clarity of the words was paramount.

Experimented with sounds of the accompaniment to create an other-worldly, timeless atmosphere that was simple enough not to obscure the text.

For the Adam lay ybounden poem:

Spent time saying the poem out loud while moving (and sometimes drumming) to find the rhythms intrinsic in the poem, experimenting with different time signatures for different parts of the poem.

Thought long and hard about the poem, and which bits of the text should be repeated (eg four thousand winters).

Worked at the melody and harmony so that the three time sections could be combined together to create the atmosphere of a party and celebration.

Experimented with the two text settings together and how one could lead to/balance the other.

Taught some of the junior members of Leominster Priory Choir the music ready to record. I wanted children’s voices to be part of it because of the particular tone, but also because it symbolises the universality of the meaning of the poem which continues to be relevant through the ages.

Recorded the different elements of music, including adding extra parts in to the repeated sections to give the impression of people joining in as the celebration continued.

Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) - King Arthur at Avalon (study) detail © Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales

Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) - King Arthur at Avalon (study) detail © Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales Apple Records’ Granny Smith

Apple Records’ Granny Smith