Apple Good, Apple Bad

The poisoned apple is a paradox, both alluring and potentially deadly.

“What fruit”, asks Edward Bunyard in his 1929 book ‘The Anatomy of Dessert’, “can compare with the apple for its extended season, lasting from August to June, keeping alive for us in winter, in its sun-stained flush and rustic russet, the memory of golden autumnal days?” The apple’s simple form, juicy taste and satisfying crunch has awarded it status as a symbol of goodness, even projected onto humanity. The idiom ‘the apple of thine eye’ appears in various forms throughout the English translation of the Bible, to mean something or someone cherished above others. Yet under the apple’s skin occasionally lurks rotten flesh – a ‘bad apple’ about to contaminate its neighbours – or, indeed, poison.

From earliest times, the apple’s wholesomeness has provided temptation. The apple is portrayed in Biblical imagery as the fruit of forbidden knowledge in the Garden of Eden, enticing Adam and Eve. The fruit dangling invitingly from the apple tree lures youthful scrumping in orchards. It appeals to a basic human tendency to covet something that we know we should not have.

As such, the apple has become a symbol of ambiguity, good and bad – Shakespeare’s “goodly apple rotten at the heart”.

Snow White is the 53rd story in the first edition of folk tales compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in 1812. It features the infamous poisoned apple:

The queen stepped before her mirror:

Mirror, mirror, on the wall,

Who in this land is fairest of all?

The mirror answered:

You, my queen, are fair; it is true.

But Little Snow-White with the seven dwarfs

Is a thousand times fairer than you.

When the queen heard this, she shook and trembled with anger, “Snow-White will die, if it costs me my life!” Then she went into her most secret room — no one else was allowed inside — and she made a poisoned apple.

From the outside it was red and beautiful, and anyone who saw it would want it.

Then she disguised herself as a peasant woman, went to the dwarfs’ house and knocked on the door.

Snow-White peeped out and said, “I’m not allowed to let anyone in. The dwarfs have forbidden it most severely.”

“If you don’t want to, I can’t force you,” said the peasant woman. “I am selling these apples, and I will give you one to taste.”

“No, I can’t accept anything. The dwarfs don’t want me to.”

“If you are afraid, then I will cut the apple in two and eat half of it. Here, you eat the half with the beautiful red cheek!”

Now the apple had been so artfully made that only the red half was poisoned. When Snow-White saw that the peasant woman was eating part of the apple, her desire for it grew stronger, so she finally let the woman hand her the other half through the window. She bit into it, but she barely had the bite in her mouth when she fell to the ground dead.

Walt Disney‘s first full-length colour and sound animation film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released in 1938. In this interpretation of the folk story, a dark sequence in the film begins with the Evil Queen poisoning an apple in a bubbling cauldron.

“Dip the apple in the brew, let the sleeping death seep through…

Now turn red to tempt Snow White, to make her hunger for a bite”

Disguised as an old witch, the Evil Queen seeks out Snow White in the Dwarfs’ cottage, offering her the bright red apple from a basket of green apples.

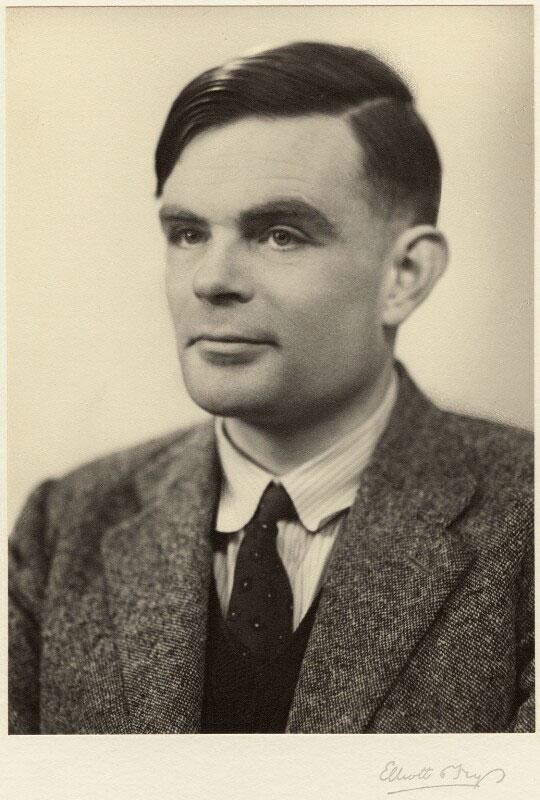

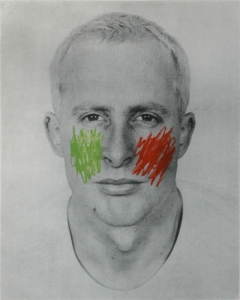

The brilliant mathematician and father of computing Alan Turing watched the film when it was first shown in Cambridge. Alan Garner, the well known writer of fantasy novels, met Turing in 1951 as a fellow amateur runner. He remembers Turing being fascinated by the scene featuring the poisoned apple, the complication in the binary decision when apple good is apple bad.

“He used to go over the scene in detail, dwelling on the ambiguity of the red and green apples, one of which gave death.”

Alan Garner

Sadly, a chain of events led to Alan Turing’s untimely death on 7th June 1954. He was found lying dead on his bed, cause of death recorded as asphyxia due to cyanide poisoning. Police Sergeant Leonard Cottrell of Cheshire Constabulary reported:

“On the small table at the side of the bed, on the right hand side, I noticed a half slice of apple. Several bites had been taken from the side of this piece of apple.”

Historically, the idea of a poisoned apple may have come about because pips within an apple’s core contain small amounts of amygdalin, a compound of cyanide and sugar. Whatever the origin, the implication of something as natural and good as an apple being poisoned is profound. Alan Turing and Alan Garner were both deeply affected by the Walt Disney film, its Evil Queen, and the poisoned apple. At seventeen, Alan Garner had already developed an interest in folk tales, including the Grimms’ Fairy Tales, when he met Alan Turing seventy years ago. They spoke at length about the deception and contradictions in the story of Snow White. Alan Garner, who was studying classics at school, recalls Alan Turing being amused to learn that the latin word malum means both ‘apple’ (noun) and ‘evil’ (adjective), and was excited by the implications of this punning coincidence: Apple good; apple bad.

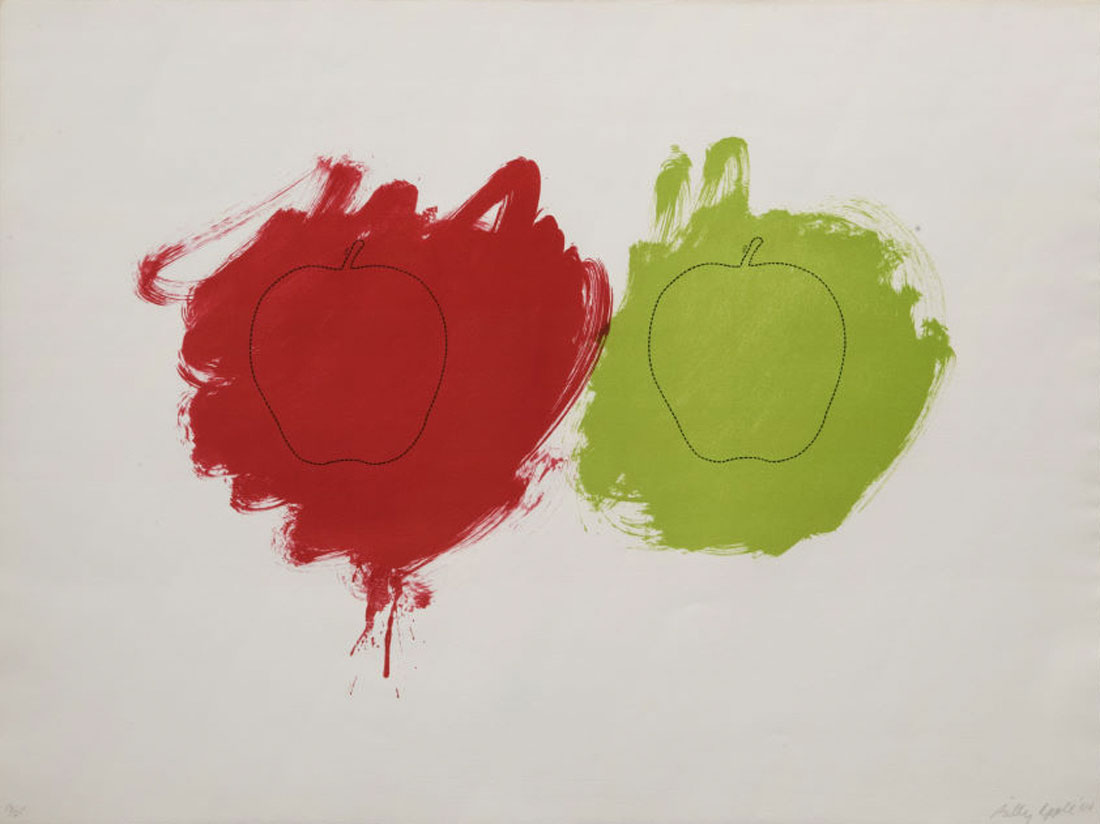

Billy Apple® – Cut 1964

Pop art trumps abstract expressionism

A pop multiple that invites the viewer to cut up the artwork thus removing it even further from the lofty realms of high art.

This is an offset lithography on T.H. Saunders paper 580 x 775 mm, printed in an edition of 25 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

“The artist invites you to cut along the dotted line that runs across the gestural blocks of colour. This will destroy the abstract artwork but you will be left with two pop apples in red and green, a mnemonic for Apple’s new brand identity created by his name change in London on Thanksgiving Day, 1962.”

Billy Apple® is one of the pop art generation. In 1962 he established his art brand in London with a name change and adopted red and green as his brand colours. He made art works with apples as visual aids to support his new identity. This self-branding exercise gave him the freedom to reinvent himself unencumbered by art history. Today Apple has worked with horticulture scientists, intellectual property lawyers and cidermakers to make contemporary art. He has used red and green branding throughout his career to denote the different types of apple, their state of ripeness, and port & starboard sides.

Read a later ‘Journal of Apples’ article about Billy Apple® published on 24th November 2022

Sources:

- Bunyard (1929) The Anatomy of Dessert

- Grimm Brothers (1812) Sneewittchen in Kinder und Hausmärchen [translated Professor Ashliman, University of Pittsburgh]

- Hodges (1983) Alan Turing: The enigma and 2014 update www.turing.org.uk

- Hodges (2016) Alan Garner and Alan Turing: On the Road

In Wagner ed (2016) First Light: A celebration of Alan Garner - Kings College Cambridge Online Exhibitions: Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954)

- Leavitt (2006) The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer

Thanks to:

- Billy Apple® www.billyapple.com

- Professor D L Ashliman, University of Pittsburgh USA www.pitt.edu

- Alan Garner OBE, novelist www.alangarner.atspace.org

- Professor Andrew Hodges, University of Oxford UK www.synth.co.uk

- Christine Hourdé, Gallery Director, Mayor Gallery, London www.mayorgallery.com

Fruit Label © Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center

Fruit Label © Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center Emily Gravett - Bear Apple © the artist

Emily Gravett - Bear Apple © the artist