American Apples and Latino Grit

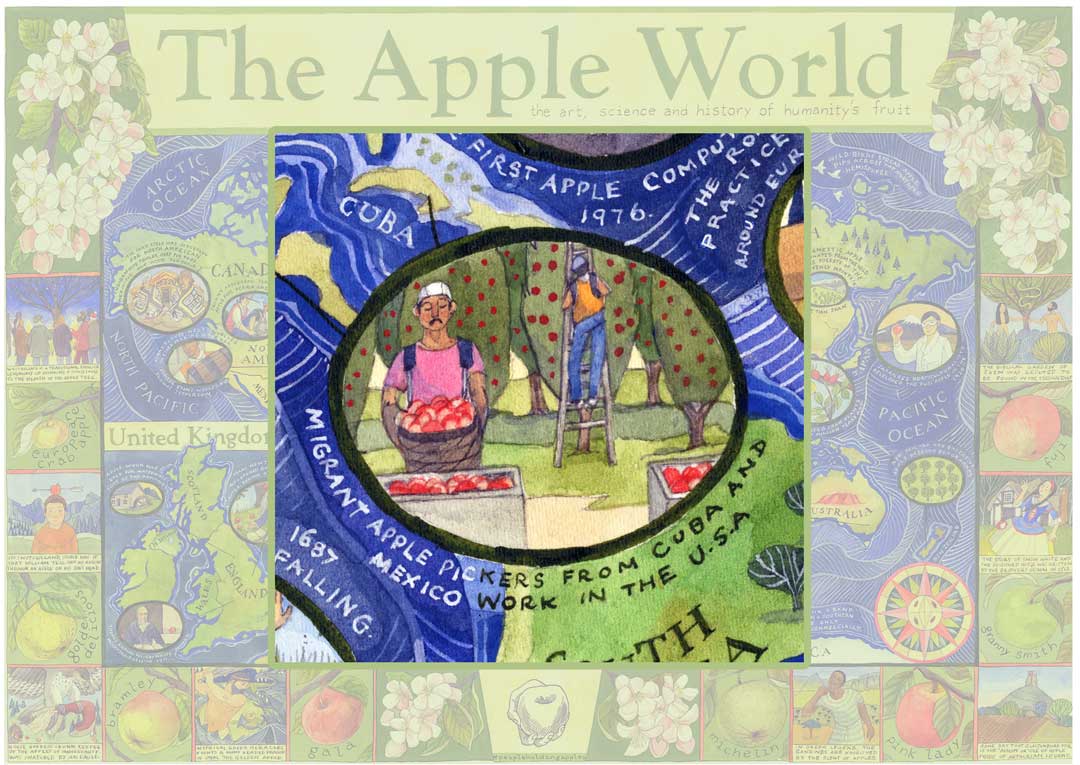

Latin American migrants work in orchards and packhouses in Washington state

More apples are grown in the United States of America than anywhere else in the world, after China. Few growing regions can compare with Washington state, in the northwest corner of the U.S. – which grows two-thirds of America’s apples. East of the Cascade Mountains, in the middle of the state, conditions are nearly perfect for healthy orchards and fruits: well-drained volcanic soils, plenty of water, and a climate featuring warm, sunny summers and cool autumn nights. (Seattle, Washington’s best-known city, is west of the Cascades and receives too much rainfall to produce good tree fruit). North Central Washington orchards produce around 100 million boxes of apples each year, equivalent to about 12 billion apples which, if laid side-by-side, could circle the planet 29 times!

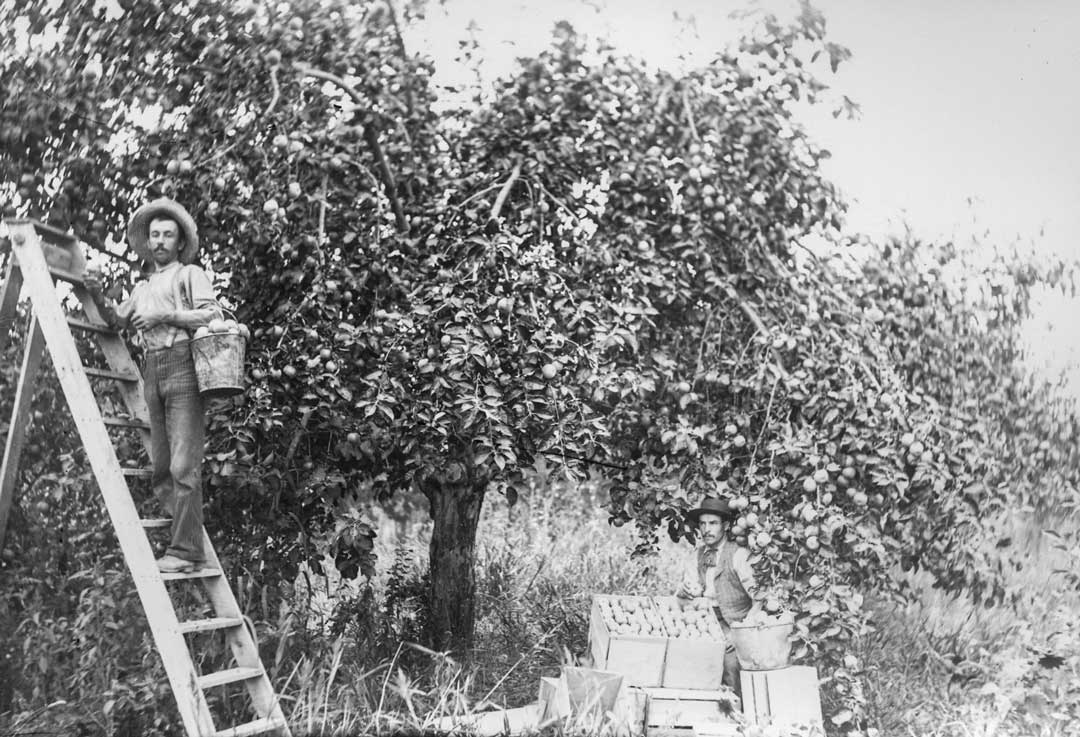

Apples have been the backbone of the economy of North Central Washington since 1900. A century ago, teenagers were excused from school in the fall to help bring in the apple harvest. Some Native Americans became orchard workers in the early 1900s. During the Great Depression, when many farmers in the south-central U.S. lost their farms because of drought (the “Dust Bowl”) or poverty, these farm families migrated to California, Oregon and Washington to find work.

They made up the majority of the labor force for pruning, thinning and harvesting apples until the U.S. entered World War II in 1941.

At this point, with many men joining the military to fight in Europe or the Pacific, orchard owners faced a crisis. Who would pick the apples when they came ripe? Throughout fertile California, who would tend the tomatoes and lettuce and citrus trees?

This emergency demand for labor caused the U.S. government to establish the Bracero Program. The U.S. contracted with Mexico to send millions of male farm workers to come north for short-term employment. They were guaranteed decent living conditions (sanitation, adequate shelter and food) and a minimum wage of 30 cents an hour, as well as protections from forced military service.

The bracero, meaning “one who works with his arms,” was crucial to the tree fruit industry of the Pacific Northwest into the 1950s. The Mexican men generally arrived in June for thinning and stayed through October harvest before returning home. Growers were grateful that these laborers were able to save the cherry, pear and apple crops as well as working in fruit-packing warehouses after harvest.

The braceros were valued as strong, dependable and energetic workers. After the guest program officially ended in 1964, some Mexicans stayed in the U.S. without permission to continue orchard work. Others crossed the border without documentation – including women and children. Tree fruit growers welcomed the Latino labor and tended not to worry about their immigration status.

Immigration laws were not strictly enforced until the U.S. enacted the Immigration and Control Act in 1986. Under this act, legal residence was granted to all undocumented migrants living in the United States as of January 1, 1982, as well as those who had engaged in seasonal agricultural work for at least 90 days during the previous years. About 32,000 immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries signed up for legal status (sometimes called “amnesty”) under the 1986 Act. New migrants, however, were strictly limited.

A civil rights movement emerged in the U.S. in the 1960s in support of Mexican-Americans, or Chicanos (also called Hispanics). It reverberated throughout Washington state, resulting in federal programs to provide farmworker housing and migrant health clinics. Meanwhile, more Latin Americans crossed the border (legally or illegally) seeking work in orchards and on farms.

By the mid-1980s, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans comprised the majority of the work force in North Central Washington’s tree fruit industry. This is still the case today. Many of them work year-round in the orchards and in packing warehouses. They are excellent employees, hard-working and dependable. Their children attend local schools and extended family networks have grown, along with the percentage of Latino residents in this region.

In Wenatchee, the population is now about 35 percent Latino. Most are of Mexican origin, but in recent years people from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and other Latin American countries have migrated to this area. Orchard and fruit warehouse work is most popular but they work in other sectors as well, including education, law and medicine.

“A great deal of labor is needed to grow, harvest, and pack apples. Without the experience and dedication of this workforce we could not continue to produce these crops, and certainly not at the high standard for which Washington apples are known around the world.”

Jon DeVaney, President, Washington State Tree Fruit Association

Traveling through North Central Washington, from Yakima and Wenatchee north along the Columbia River to Canada, one sees orchards in every direction. And working hard in these orchards are Latinos – mostly men, but some women as well. Many growers provide housing for their workers – but migrant camps have been set up here and there as well, with spacious tents and running water and refrigeration. Mariachi, banda, salsa and other Latin music plays from radios in the orchard while crews prune (in winter), thin (in early summer) and harvest apples.

Latinos also make up the bulk of employees who process the fruit after harvest. Growers usually sign on with large warehouses to sort, pack and ship their apples, pears and cherries.

Some of these firms, such as Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, offer programs to benefit the Latino community: a free health care clinic, on-site English and Spanish classes, support of the annual Fiestas Mexicanas event, and sponsorship of a soccer league (soccer is the American term for the international game of football, a favorite with Latinos).

Over the past four decades, many Latinos have risen from thinners and pickers to crew bosses. orchard managers and warehouse managers. Programs such as Wenatchee Valley College’s Hispanic Orchard Employees Educational Program (HOEEP) assist them on this upward trajectory.

This nationally recognized certificate program has been shown to increase the professional abilities of agricultural employees, and their contributions to operations

“Our industry continues to invest in our current and future workforce”

Jon DeVaney, President, Washington State Tree Fruit Association

The HOEEP course of study includes English language and communication skills, cultural and social systems (civics), mathematics, computers, current production technology, and horticultural science.

Tony López migrated from Mexico to Los Ángeles in 1968. Sent at only 14 years old, he carried the heavy burden of helping to provide for his siblings, a family of 16. After working in the food industry as a cook and a bus boy, he often held three jobs at once. He started his own family and they moved to Washington state in 1990, away from the growing crime and gang activity in east LA. Motivated by his childhood days in open fields tending to cattle, he settled in the little agricultural town of Tieton, working in apple fields as a picker and in a warehouse as a forklift driver. His work ethic and ambition to leave his five children well established gave him the courage to purchase ten run down abandoned acres of Red Delicious apples in 1995. Later, in 2005, he merged companies with his second oldest son Carlos, who now run a fruit farm of 180 acres.

Carlos is also a director of the grower-owned co-operative Cowiche Growers Inc that stores and packs fruit for its members and says that he is still learning about different aspects of the apple industry. He summarises his father’s accomplishment:

“To still be in business and be a minority Latino owner after such challenges and trials is a true testament to the grit that develops from having to leave your home town and put your family needs before your own at such a young age. The same grit that all migrants develop no matter where they are from. It also sets a precedent for all migrants to not be satisfied with just working hard, but to work smart towards a goal they can pass on to their children.”

Carlos López, López Orchards, Washington, USA

The industry’s relationship with Mexico and Latin America is two-way, not just as a source of labor. Mexico is also the largest export market, purchasing approximately 10% of the apple crop each year. And with more and more Latinos in the US now owning orchards themselves, the long relationship between Latin America and America’s Apple State is cemented.

Thanks to:

- Chris Rader, historian and author, Wenatchee, Washington, USA who wrote this story for Apples & People

- Jon DeVaney, President, Washington State Tree Fruit Association, which supports apple, pear, and cherry growers

- Carlos López, López Orchards, Cowiche, Washington, USA

- Elizabeth Price, Communications Specialist, Stemilt Growers LLC, Wenatchee, Washington, USA

- Anna Spencer, Collections Coordinator, Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center, Wenatchee, Washington, USA

- Jennie Strong, Communications and Outreach Specialist, Washington Apple Commission, which is responsible for marketing Washington apples in export markets

Ornament from Puabi’s diadem of gold and lapis lazuli. With kind permission of Penn Museum, Philadelphia, USA ©

Ornament from Puabi’s diadem of gold and lapis lazuli. With kind permission of Penn Museum, Philadelphia, USA © Crispin van den Broeck - Two young men c1590 © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

Crispin van den Broeck - Two young men c1590 © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge