The Bird and The Apple

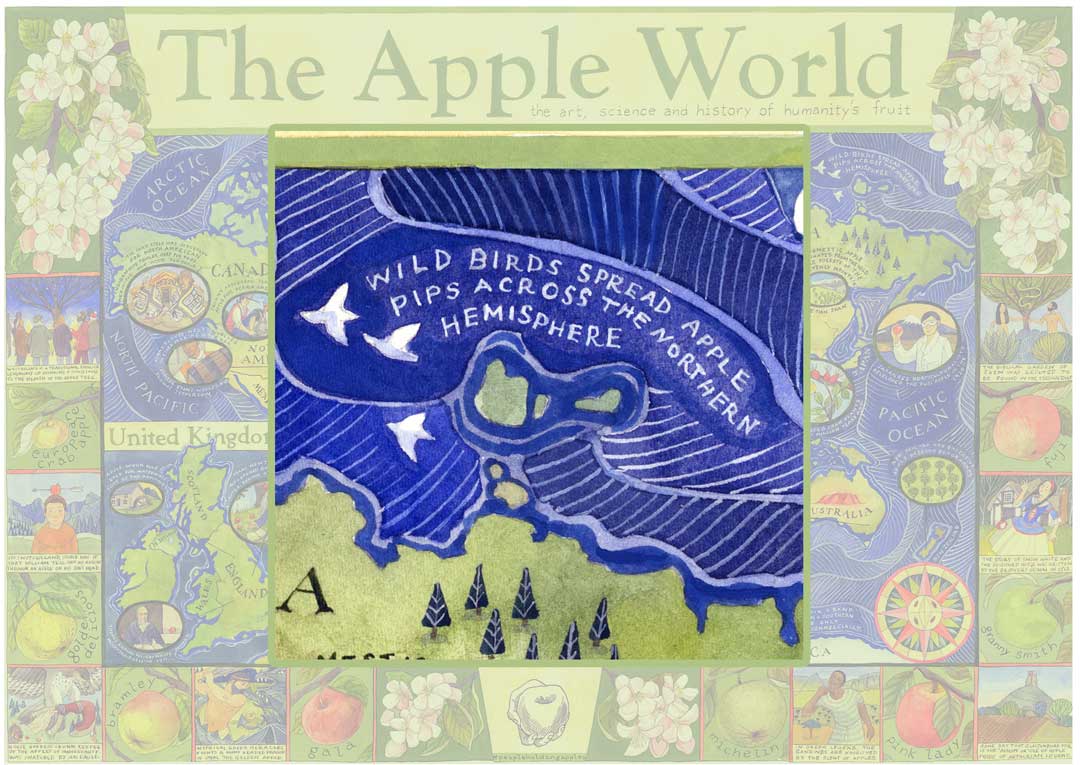

Eating the fallen apples, birds spread apple pips across the northern hemisphere

Birds loiter in the background of Crispin van den Broeck’s alluring sixteenth century painting of two young men holding an apple. From the cloudy background a raven’s head juts out from behind the head of the boy in red, while two dark, scarcely focused owls’ faces peer over each shoulder of the boy in black. Both birds are ill omens, portents of death, and the hypothesis is that this painting is a message about mortality – behind the carefree happiness of youth lies the chilly obscurity of death.

In an orchard, birds have an important role in the end of life of the apple, cleaning up beneath the apple trees and in turn spreading pips – and new life – through their droppings. Here, in an excerpt from ‘The Orchard: A Year in England’s Eden’, Nicholas Gates eloquently describes the activity taking place in one Herefordshire orchard during January:

‘Tack-tack-tack’. The repeating alarm notes of a song thrush. ‘Tzeeee. Tzeeeeeeeee.’ A greenfinch announces his presence. A powerful little resonating trill fires out of the thorns as a wren deftly disappears back into the hedgerow.

Walking further into the orchard, between aged Kingston Blacks and perry pears, a conveyor belt of movement lies ahead. A sweet aroma, the hybrid of fresh silage and a forgotten fruit basket, betrays an abundance of rotting apples below every tree.

Taking aim through binoculars, the mirage ahead turns into living chaos, as dozens of fieldfares rotate between the lower branches and the bounty lying under the trees. The ground around their chosen tree shimmers with grey, as these large dumpy thrushes work energetically to pick apart the winter’s windfall. The fieldfares take it in turns – each spending no more than a minute on the ground before resuming watch-duty for the others. The more you look, the more you see. A careful scan of the surrounding trees reveals an extensive feeding flock of at least five hundred fieldfares. This orchard – a postage stamp, relative to the size of the surrounding landscape – is giving them exactly what they need to get through the winter: a seasonal magnet in an empty land.

These Vikings are fleeting visitors. Fieldfares breed in Scandinavia and north-eastern Europe. Yet as little as a month after fledgling, the first snow arrives in their homelands. From September onwards, huge numbers descend on eastern England, drawn by the genetic memory of richer pastures. In a particularly cold Nordic winter, up to a million birds can arrive, favouring the more temperate climate of our ocean-warmed island. Today, the mercury registers a brisk one degree Celsius. But if these fieldfares hadn’t hopped the North Sea, these birds would be now experiencing the full force of a hyperborean winter – regularly dipping below minus 30 degrees in a landscape so harsh that in large parts of Scandinavia, even the wolves and elk will move south for the winter.

As soon as they arrive in Britain, fieldfares are desperate to refuel. Fortunately, they are not fussy, with one of the most varied diets of all thrushes. In the summer, invertebrates are top of the menu. Come the autumn they switch to berries – drawing them into gardens across the country as they raid our hawthorns, rowans and cotoneasters. It’s not unusual for a feeding flock to stay loyal to a single berry-laden tree while picking off every morsel. But as these run out come the winter, fieldfares seek out larger fruits, in sympathetically managed orchards where windfall is left. They can stay for months, until every rotting fruit is gone.

‘The Orchard: A Year in England’s Eden’ is a month-by-month account of one Herefordshire orchard. It documents the abundance of life in the orchard throughout the seasons from the flowering of the trees to the ripening of the fruit and the mammals and birds that feast on the windfalls.

Thanks to:

- Benedict Macdonald and Nicholas Gates for allowing us to share this passage from their book ‘Orchard: A Year in England’s Eden’ published in 2020 by William Collins

Alicia López packing Honeycrisp apples at Cowiche Growers Inc Photography Manuel Tavira Courtesy of Carlos López

Alicia López packing Honeycrisp apples at Cowiche Growers Inc Photography Manuel Tavira Courtesy of Carlos López Payne Limner - Alexander Spotswood Payne and His Brother John Robert Dandridge Payne, with Their Nurse 1790-91 © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA. Gift of Miss Dorothy Payne. Photo Katherine Wetzel.

Payne Limner - Alexander Spotswood Payne and His Brother John Robert Dandridge Payne, with Their Nurse 1790-91 © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA. Gift of Miss Dorothy Payne. Photo Katherine Wetzel.