Bramley’s Seedling

Big apples from little pips

The story starts with a family called Brailsford who lived in a cottage on Church Street in the village of Southwell in Nottinghamshire, UK. The family had two daughters and sometime about the year of 1809, the eldest daughter, Mary Ann, decided to plant some pips in a flowerpot, which were taken from apples being prepared in the kitchen by her mother.

One of these pips germinated and, when it was too big for the pot, was planted in the garden of the cottage and produced a tree that was later to bear a unique apple.

Mary Ann married and moved out of the house in 1813. Following the death of her parents, the house (with a mature apple tree in the garden) was sold and in 1846 was bought by Matthew Bramley, a butcher.

In the autumn of 1856, Henry Merryweather, 17-year old son of a gardener, encountered a man carrying a basket of very fine apples. Henry was impressed by their size and quality and, enquiring where they came from, the man told him they were old Mr Bramley’s.

“I at once went to see Mr Bramley and his apple tree, which was full of beautiful fruit.”

Henry Merryweather

Mr Bramley allowed Mr Merryweather to take cuttings, on the condition that if commercialised it should bear his name. Mr Merryweather grafted the cuttings onto rootstock in his father’s nursery, to grow trees to sell. He named the apple Bramley’s Seedling.

By 1876, the Royal Horticultural Society’s Fruit Committee reported “a new kitchen Apple called Bramley’s Seedling, of large size and excellent quality.” Awarded a First Class Certificate at the 1883 National Apple Congress, Mr Merryweather declared it to be the finest apple that was ever produced,

“The King of all Apples”

Bramley’s Seedling orchards were extensively planted in England in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. With mainstream agriculture in depression, farmers were encouraged to establish orchards for home-produced fruit. In the UK, the Victorians had chosen to divide apples into dessert for the dining table and culinary for the kitchen, and only in the UK is the culinary apple a significant segment of the market. Therefore culinary apples did not have competition from imported fruit and demand also benefitted from what has been described as the “democratisation of fruit” for urban populations in this period.

Bramley’s Seedling has become the premier single-purpose culinary apple. Because it gains size before fully ripe and stores well to provide year-round availability, it attracted commercial growers, and its high malic acid and Vitamin C content, and good texture, allured the nation’s cooks. A Bramley keeps its form if baked whole, and when stewed its texture retains firmness or can make a smooth, thick puree. Maintaining high acidity when cooked, Bramley holds its apple taste even with the addition of other ingredients, such as in a blackberry and apple pie. Research by the UK’s Good Housekeeping Institute confirmed Bramley’s superior appearance, flavour and texture over dessert apple varieties when cooked in popular recipes like apple pie and, currently, Shizuoka University in Japan is studying how the Bramley’s cell wall material makes a smooth paste in shorter heating time than Japanese varieties like Fuji.

Bramley’s Seedling is a triploid, meaning that it has three sets of chromosomes in each cell. Most plants and animals have two sets of chromosomes, one from the female parent and one from the male parent. Triploidy occurs when the female cell is fertilised and by chance ends up with three sets of chromosomes. This is passed on to every cell as the new plant develops and may cause more vigorous plants and larger fruit. It is unusual but not unique in apples – Blenheim Orange, Baldwin, and Jonagold are other examples. The variety of apple that Mary Ann’s mother was cooking that day two centuries ago is unknown (Blenheim Orange has been suggested as a parent) but, whatever it was, it was special because a chance happening when the blossom was pollinated to form it led to an apple genetically predisposed to be large, as would be apples from its descendants. And the apple’s size, coupled with its handling and cooking qualities, was important for its success.

Kent grower Peter May, a regular winner of the annual ‘Five Heaviest Apples’ competition at the UK’s National Fruit Show, doesn’t take any special measures to grow his huge Bramley apples but thinks that Kent’s Wealden clay soil may help.

Bramley’s Seedling is little grown elsewhere in the world. Although there is some cultivation in Northern Ireland, Japan, USA, Canada and Australia, the vast majority of commercial production is in Kent in the South East of England. Fourayes, the UK’s largest grower, buyer, and processor of Bramleys is based near Sittingbourne, Kent. Here, each year, Bramley apples are diced and sliced to the specifications of commercial customers and some 8,000 tonnes of apple product supplied in bulk, for example to bakeries for cakes and pie fillings.

The original Bramley tree blew down in the early twentieth century but did not die. Now owned by Nottingham Trent University, at over two hundred years old it is showing its age and suffers from honey fungus in its roots.

It was considered important to perpetuate the original tree because other modern-day Bramley trees are the product of several generations of grafting from the original, which will have accumulated small changes as a result. Research had indicated that the fruit of the original tree has superior flavour and texture to that from grafted trees.

In 1990, Mary Ann’s tree was the subject of a tissue culture cloning trial by Professor Edward Cocking and Dr Brian Power, bioscientists at the University of Nottingham.

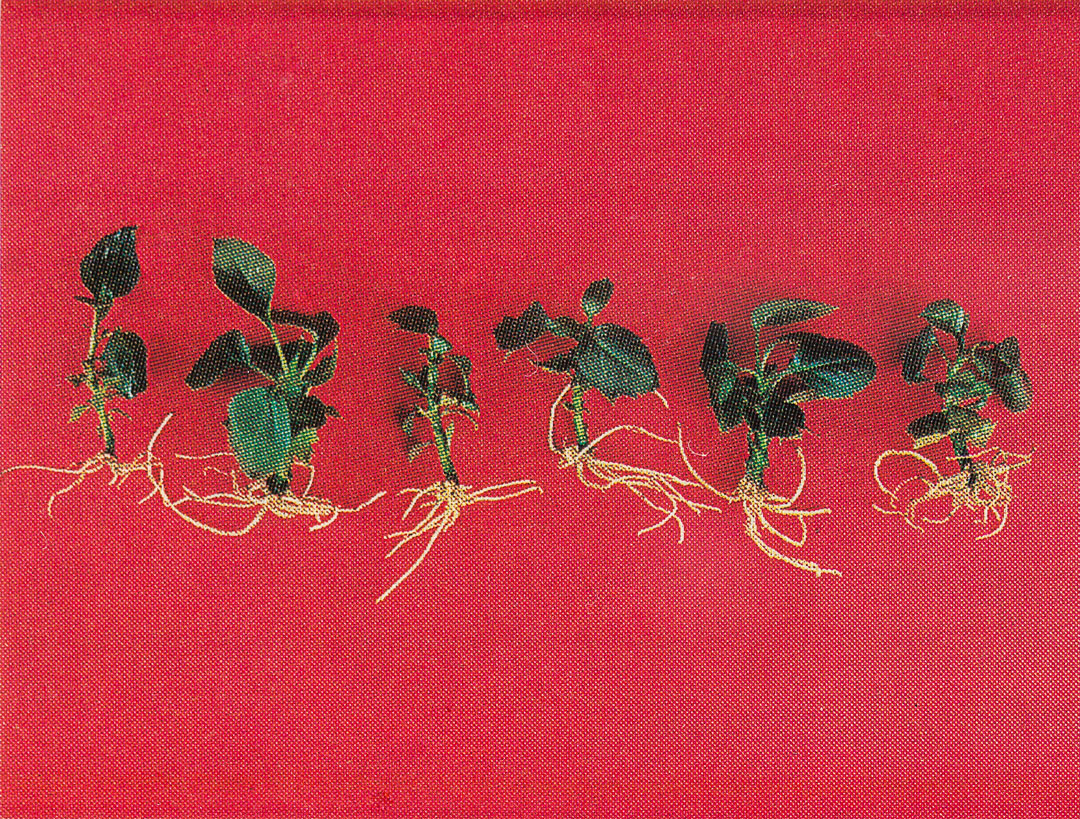

Tissue culture cloning is possible because the DNA in every cell nucleus holds all the information necessary to convert the cell back in the whole plant, provided the cell is placed in a suitable growth medium. Shoot tips taken from the original Bramley tree were cut into smaller pieces and treated to eliminate all bacteria, fungi, and fungal spores. Placed in a liquid nutrient growth medium that was refreshed every four weeks, tiny cloned self-rooted plantlets were raised. When their roots had reached three centimetres in length, the plantlets were planted in rooting growth medium.

The resulting trees are now identical cloned copies of the original tree, turning back the genetic clock to a time when Mary Ann Brailsford’s seedling tree flourished.

It is further measure of the importance of the original tree and trees grown from its cloned plantlets that two universities have been studying their fruit. Nottingham Trent University is researching the genetic profile of part of its DNA to identify the functional regions of the genome that determine the Bramley’s specific qualities, comparing fruit from the original tree to grafted Bramley trees planted locally, Golden Delicious, and a clone of the Chinese apple Hanfu.

Meanwhile, at the University of Nottingham, researchers from The Food Innovation Centre and The International Flavour Research Centre have studied apple juice flavour from cloned trees versus grafted trees, using sensory testing to assess flavour perception and by analysing the headspace aroma of the apple juices instrumentally. Cloned fruit exhibited a higher concentration of aroma compounds than grafted fruit and the nature of the aroma profile of cloned fruit was also different to that of grafted fruit meaning that the two juices might be expected to have different orthonasal characters (‘nose’ or ‘bouquet’) when aroma is assessed, before consumption.

An apple with exceptional characteristics for cooking and two hundred years of history, Bramley’s Seedling remains a firm favourite in the UK and fascinates people across the world. There is a Bramley Fan Club in Japan and a Bramley Apple window in Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire UK. Mary Ann died on 17 February 1852 (two husbands and eight children later) unaware that the pip she planted was going to cause a big stir – albeit bearing Mr Bramley’s name, not hers.

Sources:

- Barron (1884) British Apples. Report of the Committee of the National Apple Congress

- Johnson and Hogg (1876) Journal of Horticulture, Cottage Gardener, and Country Gentleman

- Juniper and Mabberley (2019) The Extraordinary Story of the Apple

- Merryweather (2018) The Bramley A World Famous Cooking Apple (from which passages about the history of the apple have been taken, with consent, for this Story)

- Morgan and Richards (2002) The New Book of Apples

- Power and Cocking (1991) How we saved the Bramley. From The Garden February 1991 with permission from the Royal Horticultural Society

Thanks to:

- Professor Edward Cocking, University of Nottingham

- David Hall, Fourayes Marketing

- Alice Jones, Senior Food Innovation Adviser, School of Biosciences, University of Nottingham

- Dr Barrie Juniper, Emeritus Reader in Plant Sciences, University of Oxford

- Tom La Dell, Trustee of Brogdale Collections, Kent

- Professor Chungui Lu and Julia Davies, School of Animal Rural & Environmental Sciences,

Nottingham Trent University - Dr Kazuhiro Matsumoto, Laboratory of Horticultural Innovation, Department of Agriculture, Shizuoka University.

- Peter May, Kent grower

- Dr Joan Morgan

- Kimi Mizuno, Bramley Fan Club, Japan

- Suzannah Starkey, Starkey’s Fruit Farm

- Celia Steven, great granddaughter of Henry Merryweather (who kindly supplied various images and much information)

- The library staff at the RHS Lindley Library in London

The Royal Gala apple, recalling Her Majesty The Queen’s visits to New Zealand

The Royal Gala apple, recalling Her Majesty The Queen’s visits to New Zealand Concept art of Johnny Appleseed planting a tree for Walt Disney’s animated short Johnny Appleseed (1948) © 1948 Disney

Concept art of Johnny Appleseed planting a tree for Walt Disney’s animated short Johnny Appleseed (1948) © 1948 Disney