Apples at the Edge of Wilderness

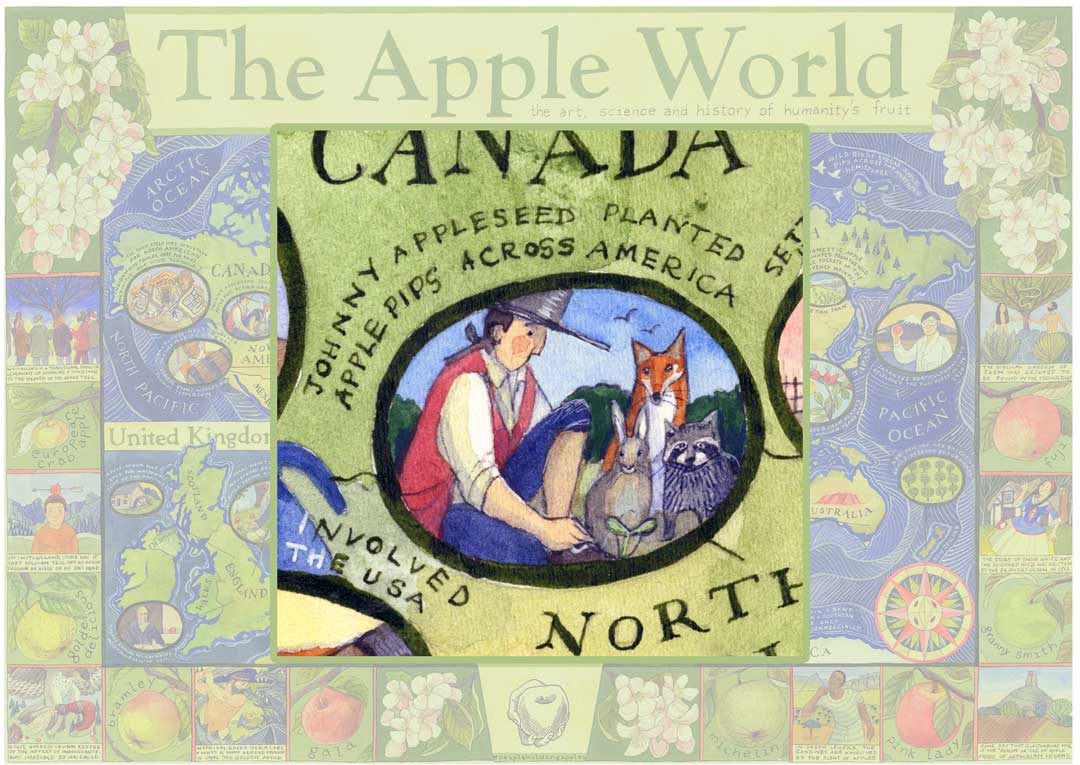

John Chapman planted apple tree nurseries to supply American pioneers

John Chapman was born in 1774 in Leominster Massachusetts (named after the market town in the north of Herefordshire, UK). He was a fifth generation American, growing up surrounded by apple orchards and the rumblings of war. Effectively orphaned when his mother died after childbirth and his father away fighting the British, Chapman was probably cared for by relatives during his early childhood until his father remarried.

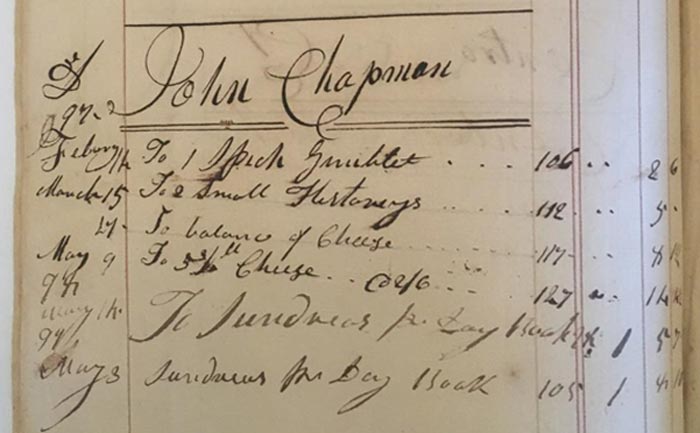

At the age of twenty-one he was walking west along Indian trails and soon afterwards planted his first apple seed nursery on the banks of the Brokenstraw Creek, in North West Pennsylvania. The earliest known remaining record of his existence is in John Daniel’s Ledger, the account book of a nearby trading post and tavern where he bought a carpentry tool, books, and cheese.

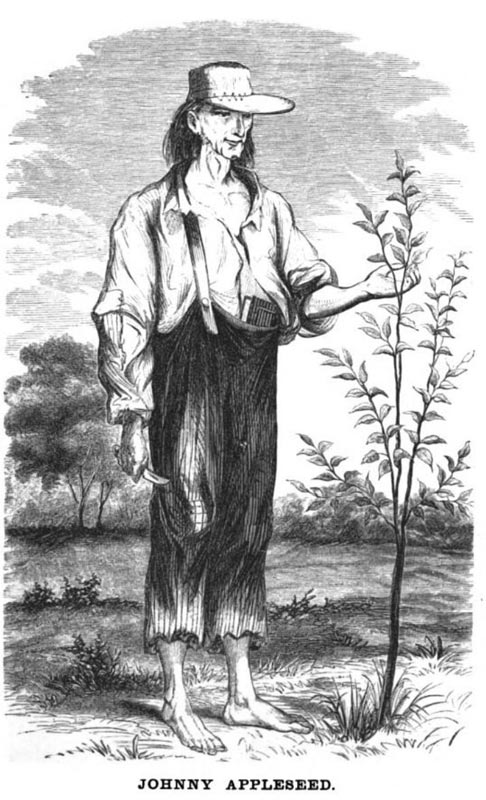

Chapman lived a peripatetic life at the edge of society between the European settlers and the native Americans. He lived lightly, few original documents from his life remain save the occasional record of supplies or land purchases. There are no contemporary pictures.

The business model he developed was cutting edge, responding to a need of the time. Collecting free apple pips from cider mills in the east he walked and canoed large distances westwards to the edge of the wilderness to plant small temporary nurseries, generally alongside rivers.

In these nurseries, cut from the wild and then left for long periods untended, he planted large numbers of apple pips, some of which would manage to grow to seedlings that Chapman could sell to settlers when they arrived to set up homesteads. His frugal existence meant minimal overheads.

Under Pennsylvania law, settlers needed more than a cabin to show the authorities that they had established land rights, and planting seedling apple trees was a way to demonstrate this.

When Pennsylvania became too domesticated, Chapman travelled further west into Ohio, where the pre-requisites for an “actual settler” to receive free land from the Ohio Company of Associates were building a cabin, clearing 15 acres of pasture and planting 20 peach trees and 50 apple or pear trees within three years – and being armed, ready to defend it.

Chapman moved back and forth to check on nurseries and to collect seeds from Pittsburgh cider mills. Later, he ventured even further west into Indiana, where he died on 18th March 1845. His obituary in the Fort Wayne Sentinel reads:

“Well known through this region by his eccentricity and the strange garb he usually wore”

Chapman became a follower of the Swedish spiritual writer Emanuel Swedenborg and developed a deep understanding of his complex texts. Chapman also believed that physical deprivation on earth ensured “a greater fullness of celestial bliss” (according to his contemporary John Dawson writing in the Fort Wayne Sentinel in 1871) which may have been a reason why he apparently walked barefoot, perhaps wore a saucepan as a hat, and preferred to sleep outdoors.

Economically, he was not a pauper. He bought, sold, and leased many tracts of land during his life and sometimes used seedlings as currency: For example, in 1828 he leased three orchards on the edge of the Black Swamp, the rent for one of which was 100 trees per year.

Henry David Thoreau does not refer to Appleseed when he wrote his 1862 essay ‘Wild Apples’ but he describes the distinction between seedlings, grown from pips, and grafted fruit which Thoreau describes as bland and uniform (and commercially successful). He describes seedlings as wild apples and equates them with a hardy pioneer, often bitter and gnarled, but sometimes “all the sweeter and more palatable for the very difficulties it has had to contend with.”

“From Chapman’s vast planting of nameless cider apple seeds came some of the great American cultivars of the nineteenth century”

Michael Pollan

Seedlings had many advantages – for settlers they were far cheaper than grafted trees and more robust, and for the nurseryman pips could be more easily transported for planting than young trees and required less attention. For Chapman, contemporary accounts also speak of his passion for growing apples.

“Sometimes in speaking of fruit, his eyes would sparkle, and his countenance grow animated”

Miss Rosella Rice

However, the disadvantage of seedlings was that the quality of the apples from a seedling is unknown, often a ‘spitter’ fit only for fermenting into cider or applejack.

First-hand accounts, after his death, describe Chapman as a man of rugged meekness, great physical strength, and peculiar habits. Whether in his life he was driven by economics, altruism, or chose a primitive Christian existence, within thirty years of his death the story of John Chapman’s life had been transformed into Yankee saint Johnny Appleseed. His wandering tree planting suited the narrative of America transforming to a civilised society.

In the 1948 cartoon Melody Time, Walt Disney depicted Johnny Appleseed as a humble hero, at one with nature, inspired to plant apple trees in the wilderness to spread joy amongst the pioneers and Indians.

“there was perhaps no more benign symbol to celebrate the process of American empire-building”

William Kerrigan

Sources:

- Kerrigan (2012) Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard

- Means (2011) Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story

- Pollan (2003) The Botany of Desire

- Pucci and Cavallo (2021) American Cider

- Private Acts of the Second Congress of the United States (1792)

Thanks to:

- Margaret Adamic and Max Raley, Disney Enterprises Inc

- The Johnny Appleseed Educational Center and Museum, Urbana, Illinois, USA

- Professor William Kerrigan, Muskingum University, Ohio, USA

- Warren County Historical Society in Pennsylvania

Bramley Apple Story

Bramley Apple Story Our Crab Apple Mothers

Our Crab Apple Mothers