Life with more than one Granny

Granny Smith and how her apple made an Australian family

The Granny Smith apple, an Australian chance seedling, is number six in the world apple production league. In Australia it is a firm favourite of growers, easy to manage and its distinctive bright green skin means no chasing colour. ‘Grannies’ generate good margins and have consistently been Australia’s third most grown apple in recent years. The Granny Smith is also the maternal grandmother of Cripps Pink, branded as Pink Lady ®, Australia’s number one apple.

Here, Jon Doust tells how the Granny Smith apple has been a constant throughout his life in Western Australia.

In the beginning, I thought there was only one apple, the Granny Smith. It was what we saw, ate, cooked, and what we kept in the basement.

After we moved out of our first house in Googilup (place of the gilgi, a small fresh water crustation, much prized by the Googilup People of the Noongar Nation), to set up short term accommodation opposite the town’s tennis courts, we spent a lot more time in our grandfather’s orchards on the edge of town.

Pop’s place sat alongside the northern bridge. There was another on the southern side of town and many people thought this was what gave it its colonial name, Bridgetown. But not so, it was named after a ship because the ship of that name was the first to berth in the region’s port, Bunbury, to load wool.

Pop was a Green when it was just a colour and he lived a bit like I lived when I later became a hippy. It was at his place that I noticed the other apples – Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Yates, Dunn’s Seedlings, Doherties, Cleopatras and Jonathans.

But the Granny never left me.

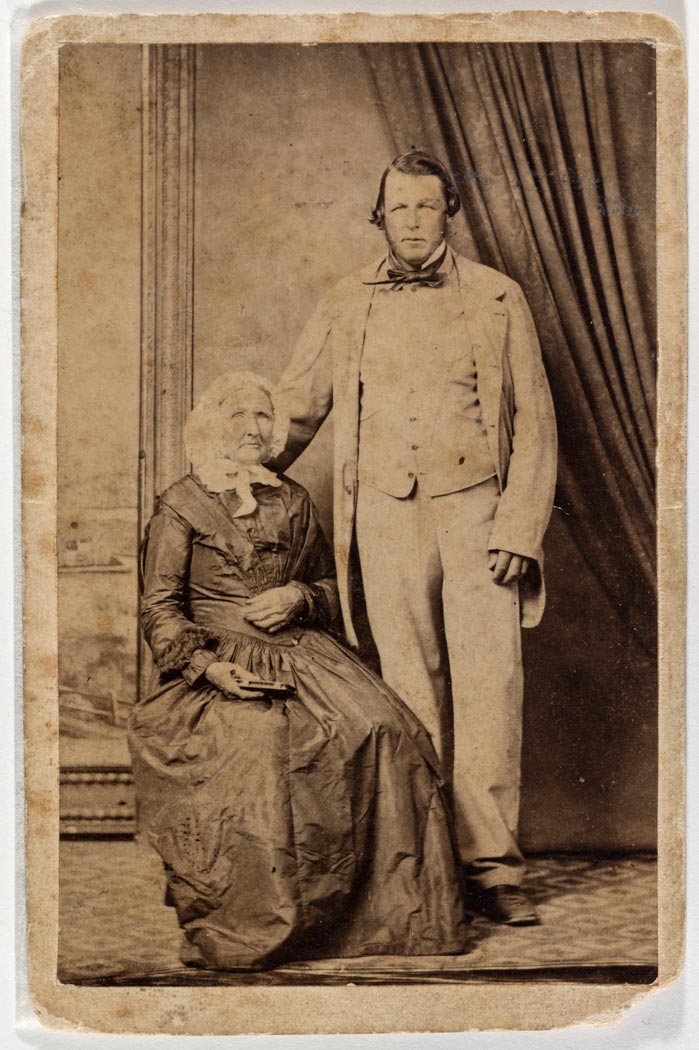

But first, let me confess that ours was an unusual family, because my real Granny and my Pop were married. Unusual? Certainly. Because my Granny was my mother’s mother and my Pop was my father’s father. The others had left, my father’s mother to an early grave and my mother’s father was divorced by her mother.

The two remaining grandparents soon realised they were made for each other – they made each other laugh and they worked and lived well together, so they took the apple by the stem and got married.

And we all lived happily in the orchards.

Pop had about ten acres around his place and then our dad, Stan, once we had moved up onto an adjoining property, planted about twenty.

With thirty acres to our name, we were then considered medium to big time apple producers and we all worked our guts to the gristle to get the fruit picked, sorted, packed and on a ship to England.

The Dousts did not send their fruit to the local packing shed.

The four boys picked, Pop made the boxes from jarrah slats, Betty (our mum) and Mabel (her mum and Pop’s wife, and dad’s mother-in-law and stepmother) sorted and packed, and Stan drove around issuing instructions.

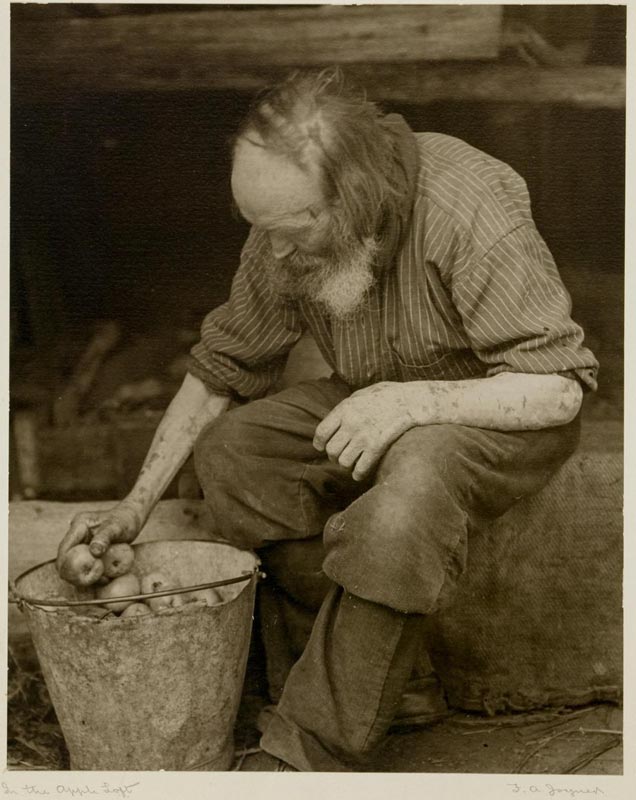

Seared into my memory is the image of Pop, mouth full of nails, laying a slat, snatching a nail, placing it, down with the hammer, once, twice, maybe thrice. The same for every drilled hole: place, snatch, bang bang bang. Such rhythm, such mastery. It has been an aim all my life, to complete simple, manual tasks with rhythm, flow and poetic motion.

These were happy days for the Doust family. We’d spend all day in the orchards, eat there, defecate there and tumble home exhausted, fight over the two showers, then eat and play a game that I never connected with, usually canasta, or Monopoly.

After repeated attempts to disrupt the natural order of a game, they would expel me and I would be forced to find a book, slump in an armchair and read. They knew that was where I always wanted to be anyway, but they did their best to entice me into their rituals.

At the end of the season, with our Grannies well on their way to the Mother Country, as Gran called England, there was time to relax before the next job Stan would have us complete. But not me, I had to scour the orchards for the last fruit hanging, or on the ground, the biggest, the yellowest, the ripest, and I would eat and eat and eat and then, when my guts were distended, I would chew the flesh, swallow the juice and spit the debris. The others never joined me. I’m not sure, even to this day, that they knew what I was up to. I didn’t want them there. I wanted absolute privacy.

After I had eaten five, maybe six, I would have to dig a hole, drop my pants, squat, and allow myself to empty. I always carried a roll of toilet paper in my back pocket. Then I would go on with my search. And after another bout I would have to squat again.

You don’t want people around you when you behave like that.

By the time I got to run the orchard on my own, in 1970, the industry was well into decline.

We were lucky because we owned two supermarkets through which we could sell our Grannies and then there was the fruit juicing factory that opened in 1971, just over the highway and up the other side of the valley from our orchards.

To be fair, I was only the nominal lead hand. As usual, Stan called the shots and I fired them. It was a useful time in my life, running a supermarket and an orchard because it made it clear to me that I had no future in retail, or farming.

Not that I was a failure, but I soon realised my head was not designed for the necessary budgeting and planning. It was also the family’s last big run with the apples.

The Bridgetown apple juicing factory opened in 1971 to take advantage of the then tax rule that allowed soft drinks to be sold without sales tax because apple juice was used as a sugar and acid replacement.

Bush Boake Allen Inc were the operators of the factory. The corporation was and still is a manufacturer of flavour, fragrance and aroma chemicals for the food, beverage, pharmaceutical, and household products industries. The company’s Bridgetown facility closed in 1976 because the Labor government of Gough Whitlam, although sacked in 1975 by the Governor General, and although lauded for much of its agenda to bring the nation into the twentieth century, decided to change what many considered a “loophole” – the production of sale tax free carbonated lolly waters containing apple juice.

That was it for Doust orchards, the final nail in the coffin and, thereafter, what was not sold in the two shops, or given away, fell to the ground and who knows how many chance seedlings we failed to discover.

The apple industry was in desperate need of a lift in fortunes. Growers were clamouring for a new deity. Little did they know that a chap called John Cripps was beavering away to provide them with their “come-true” dream.

However, it was not the end of my involvement with the Granny Smiths, far from it.

When I returned home from another sojourn on an Israeli kibbutz, I decided to try for a place in one of the two local universities.

I got in on another of the Whitlam Labor Government reforms that allowed mature aged students to enter university even if they had failed high school, which I had. It was also paying students an allowance, those who could show independence from family support. In my case that was easy enough, but it took a long time for the money to come through.

My wife at the time worked in a fast-food joint and I worked in the city’s fruit and vegetable marketplace and when the Maria “Granny” Smith apples were good and ready I drove home, picked them into banana boxes, loaded them into my Land Rover Ute, drove them back to the city and sold them to cafes and the occupants of our apartment building.

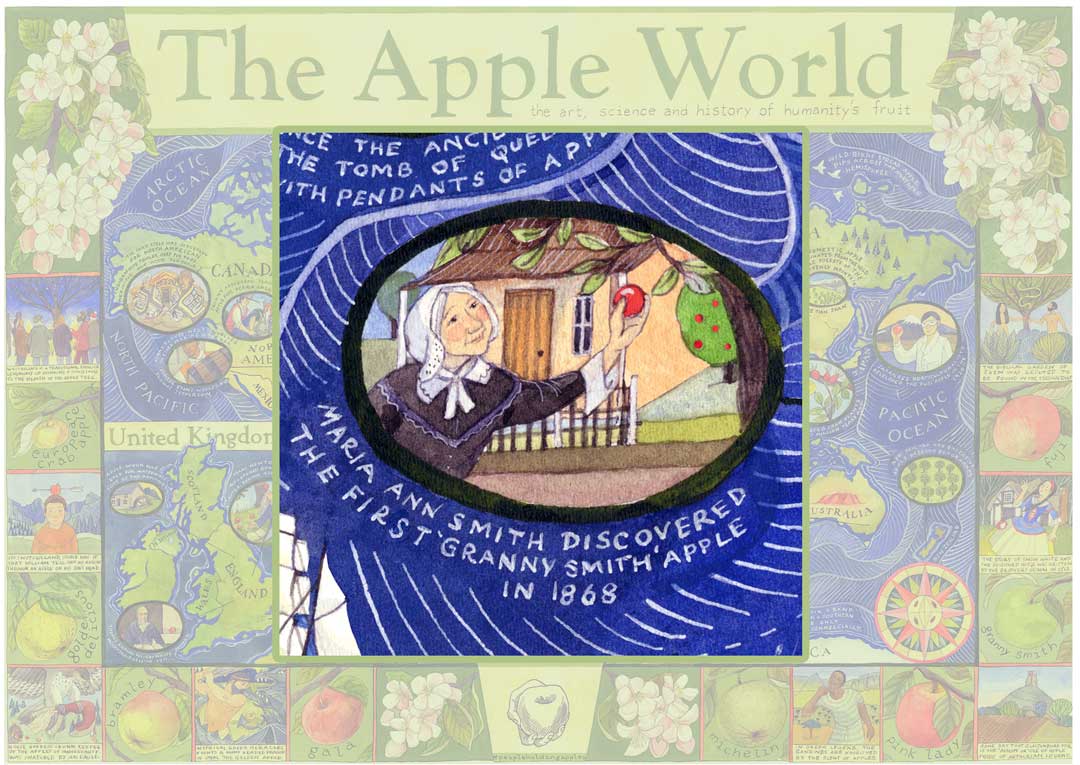

Which reminds me, I have assumed you all know about Maria Ann “Granny” Smith, the lovely lady who tossed a pile of French Crab Apples in the bottom of her garden near Sydney and by 1868 one of the seeds produced, what is still, one of the world’s most popular apples. Maria Smith died soon afterwards on 9th March 1870.

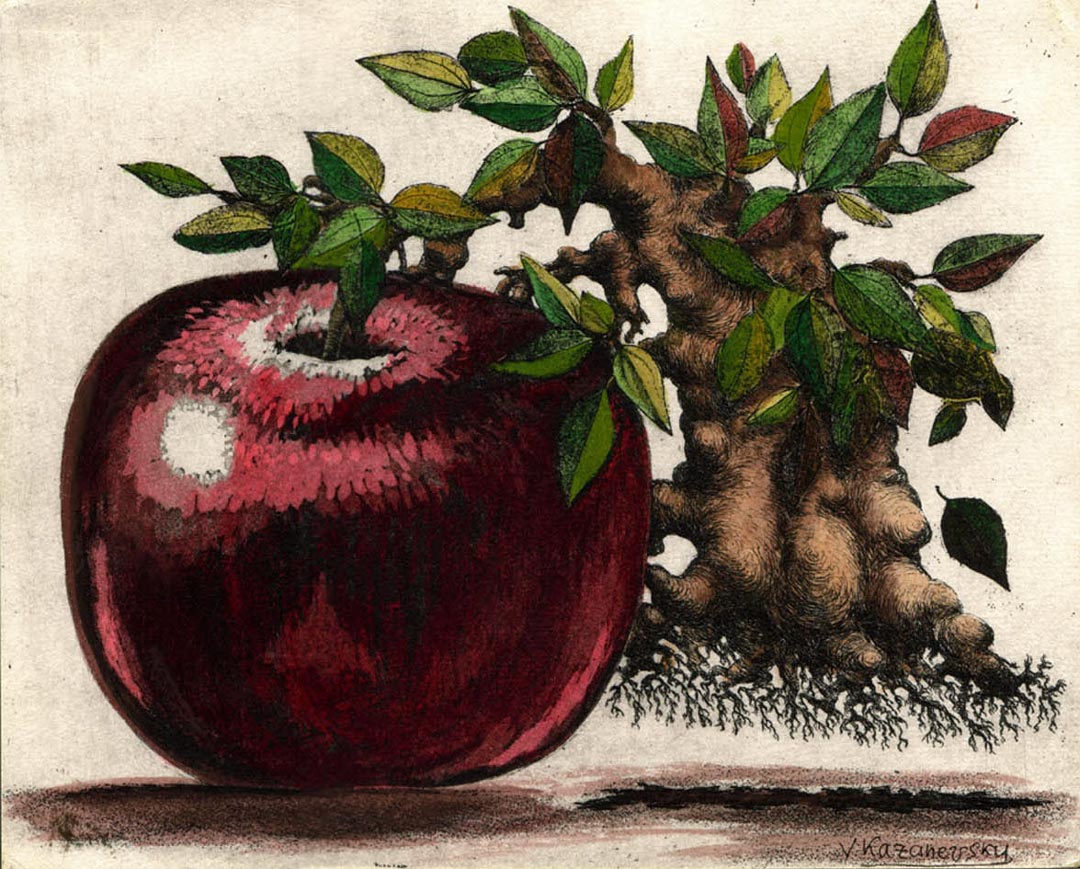

The Granny arrived by chance, but not the Pink Lady ®, Sundowner (Joya) ® or the new pome in the orchard, the so-called “black apple”, Bravo (Soluna)TM, her increasingly redder-skinned descendants. Along the way some orchardists got caught up in the new and discarded the old, putting all their eggs in the one basket. To rephrase, all their money on the one apple.

Which is why I connected with the cartoon of my old friend, the Ukrainian political cartoonist, Vladimir Kazanevsky, depicted here – one apple tree giving its all to one apple and uprooting itself in the process.

Here we are: Jon (the author), Paul, (the joker), Mum (the introvert), Dad (the leader), Jamie (the farmer who, sadly, left us behind in 2022), and Richard (the investor).

Thanks to:

- Jon Doust, author and apple lover, who kindly wrote this story for Apples & People. Jon lives in Kincinnup Kinjarling, Albany, Western Australia. Some of the words in this story will appear, although in different orders, in a book he is writing with the working title, An Apple in Your Eye, the story of the Pink Lady and other misadventures. You can find him at www.doust.com.au

- Alison Barber, Manager Communications and Media, Apple & Pear Australia Ltd

- Vladimir Kazanevsky, Award-Winning Cartoonist

Grafting: Giving Nature a Helping Hand

Grafting: Giving Nature a Helping Hand Rob Janoff Designer of the iconic Apple Computer logo Courtesy of Rob Janoff Agency

Rob Janoff Designer of the iconic Apple Computer logo Courtesy of Rob Janoff Agency