People Holding Apples

Apples and people are entwined through history

Why, four centuries ago, was a little girl painted holding an apple for this exquisite miniature watercolour portrait in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection? Why is she frowning, whilst in a companion piece another girl, probably her older sister, holds a carnation and smiles?

The varieties of apple that are eaten around the world today have been shaped by a process of human selection over generations. And conversely, throughout time, the humble fruit has been adopted as an artistic device to portray human emotion. This final apple story based upon The Apple World map explores how the humble fruit has been used in art to express different human feelings and characteristics.

The apple gift

China produces as many apples as the rest of the world combined and the Fuji apple reigns supreme. Homophonic puns are a part of Chinese spoken culture, and since the mandarin word for apple (píngguǒ 苹果) sounds like the word for peace (píngān 平安), a tradition has developed to present a gift of large, wrapped apples when visiting the family during festival holidays, and in schools and businesses, especially on Christmas Eve (píngān yè 平安夜). Artist Lottie Sweeney presents her latest model apple commissioned by the Museum of Cider for Apples & People. This is a Fuji apple from China. Lottie is comparing the newly completed model apple, in her left hand, with the real Fuji apple in her right hand.

The tempting apple

The apple was, of course, in the beginning – or so western European artists decided, when they chose to depict the fruit of the forbidden tree as an apple, the cause of the Biblical fall of man. Pre-Raphaelite painter John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s flowing Eve Tempted shows Eve reaching up to pluck the apple from the tree, the Satan-headed blue serpent whispering with steamy breath in her ear. The form of Eve is central to this work, seduced and seductive beneath the tree of knowledge, not even glancing up as she languidly grasps the forbidden fruit.

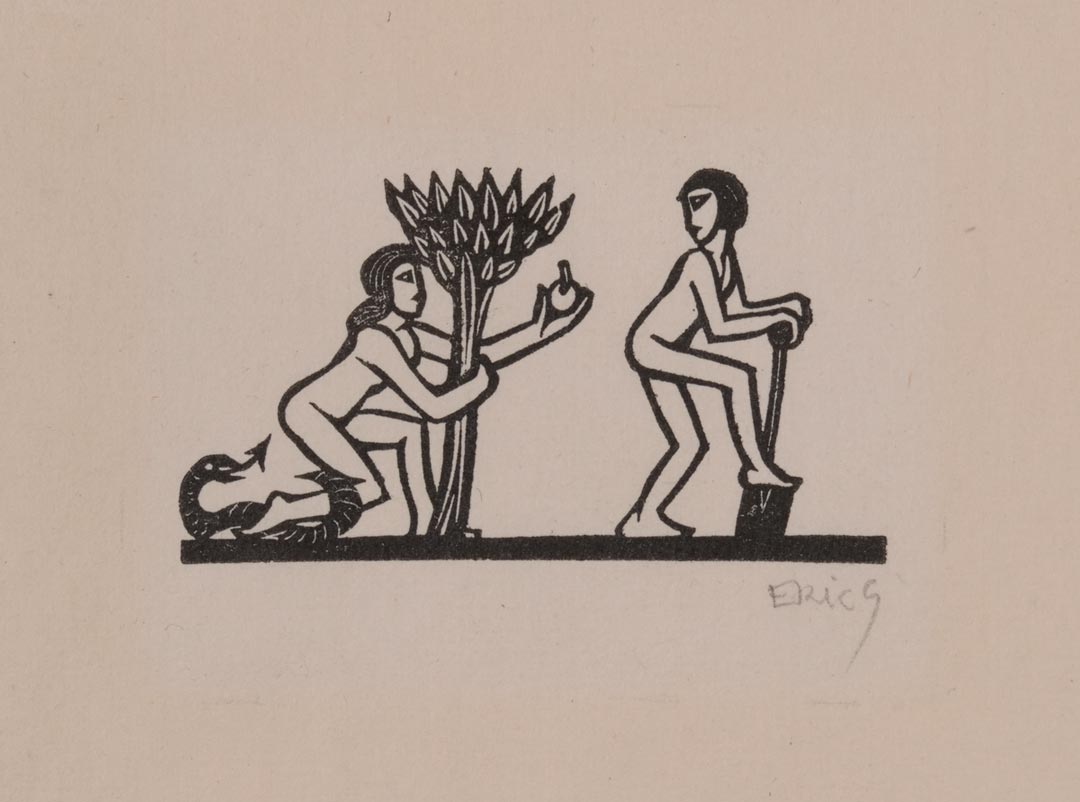

But for Eric Gill, the apple takes centre-stage. Here we see Adam happily digging in the garden, but then his eyes are drawn to the tempting apple held out by Eve, a serpent coiled around her leg. The primitive stark form of the woodcut succinctly portrays the story.

The sensual apple

In Ancient Greece the association of apples with Dionysus, the god of fruit and fertility, and Aphrodite, the goddess of love, encouraged newlyweds to eat an apple before entering the bridal chamber, because the fruit was thought to bring about ‘fruitfulness’. The apple becomes a totem of sensual desire, as in the Song of Solomon “As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste.” In this sixteenth century plate in the Wallace Collection, the serpent is coiled around the tree of knowledge echoing the curvaceous bodies of Adam and Eve, with the circular plate neatly framing the composition around the pivotal apple. But in her left hand, Eve clutches another apple to her bosom, a possible allusion that the apple assumes sexuality because the shape of the fruit suggests a woman’s breast.

In this Bowes Collection portrait, the richly-dressed sitter, who may be German princess Henrietta Katherina von Oranien, rests her right hand on a stone table firmly holding an apple, her choice from the fruit on offer. In the seventeenth century, apples, grapes and pomegranates conjured thoughts of pleasure and seduction, as well as opulence. The background of a rich landscape might suggest that the fruit had been grown in the sitter’s garden, as was becoming more common for the wealthy. Apples were popularly grown in hothouses in the seventeenth century, most notably at Versailles, which may have some significance in this French painting.

And another piece of crockery, an Italian dish in the V&A’s collection features a group of naked boys scrumping apples from a tree, which is part of the most spectacular fifteenth century maiolica service made, in Pesaro, for Matthias Corvinus, king of Hungary and his wife Beatrix, daughter of Ferdinand I of Aragon. It is believed that this was a marriage gift from Beatrix’s cousin Camilla of Aragon, ruler of Pesaro, with this dish of young boys collecting apples perhaps about hoped-for (but unfulfilled) fertility.

The apple beauty

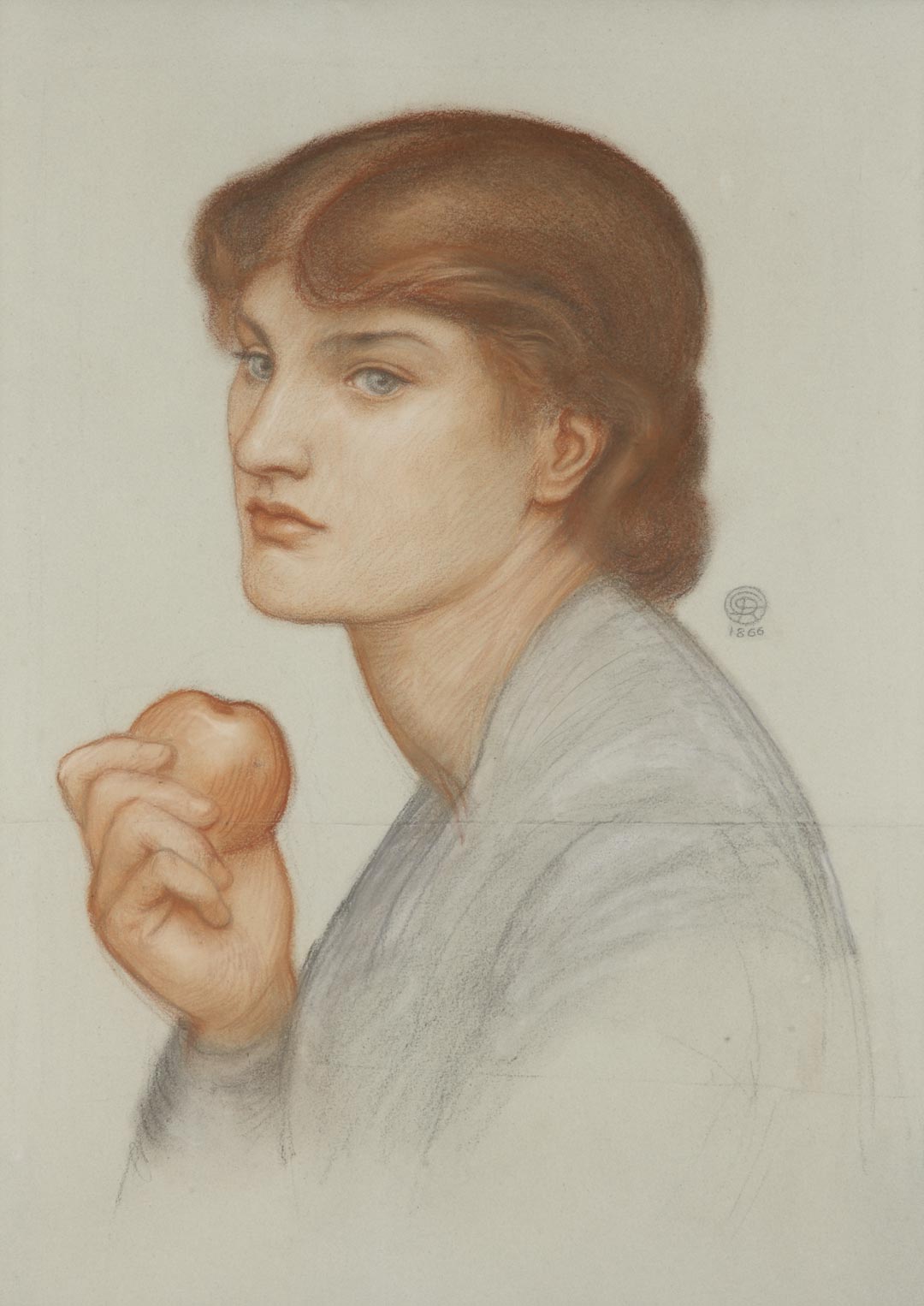

At its most simple, the apple is representative of feminine beauty, beguiling the observer, something that Rossetti captures in the simple sketch in coloured chalk of his muse Alexa Wilding. Wilding was considered to have pure, classical, beauty but, recalls Rossetti’s assistant, “sat like the sphinx waiting to be questioned”. In the sketch, the form and tones of the apple and Alexa’s head complement each other and the viewer wonders whether she has any intention to bite into the apple. “She hath the apple in her hand for thee, yet almost in her heart would hold it back” wrote Rossetti in a poem to accompany the painting Venus Verticordia (1864-1866).

A more complex treatment of beauty is Robert Hope’s lush, elegant and flowing painting ‘The Golden Apple’ which combines strong horizontal lines with two splendidly attired ‘peacocks’. Yet it is the golden apple that is the focus of attention for the peacock, woman and viewer, an apple selected from red and gold apples in the nearby basket and perhaps offered up to the peacock. The Scottish painter delivers a beautiful exercise in iridescent colours echoing from the woman’s dress, golden with blue sash, to the peacock tail and body colour. ‘The Golden Apple’ was first exhibited in the Royal Scottish Academy’s Annual Exhibition in 1919. In the Serbian poem ‘The Golden Apple-tree and the Nine Peahens’, which was first translated into English in 1874, peahens nightly raid the emperor’s apples from his tree, but one transforms into the most beautiful maiden who makes a bargain with the emperor’s son to save an apple. Peacocks are also the sacred bird of Hera, Queen of the Gods and protector of women.

The loyal apple

In this portrait of King Charles the First’s third cousin, James Stuart Earl of Darnley is also thought to be holding the golden apple. Here it is a symbol of loyalty, Darnley perhaps depicted as the Greek shepherd Paris who must decide the fairest goddess and through his choice sparked the Trojan War. Darnley’s golden locks echo the golden apple, picked from the tree behind him, and together reinforce a diagonal axis to this painting. This is one of several versions of this painting, including one in the Louvre in Paris.

Whilst the leafy fruit is recorded as an apple, it must be said that it does appear somewhat pear-like, and has also been referenced as a quince, lemon and orange.

Darnley indeed proved to be a loyal supporter of King Charles I. Later created Duke of Richmond, he negotiated with Parliament on the King’s behalf during the English Civil War and was one of the few noblemen to attend the executed King’s funeral.

The sorting apple

Apples also feature as an expression of human decision-making, perhaps most often as the golden apple of Greek mythology. Here van Dyck again takes the subject of the shepherd Paris, this time as a sensitive self-portrait. His right hand surreptitiously holds the golden apple of discord as he visibly deliberates before awarding the apple to the most beautiful of the three goddesses.

Meanwhile on the streets of New York, this assured drawing captures the forceful personality of an anonymous girl whose anxious yet determined expression suggests she is steeling herself for a confrontation, perhaps with other children trying to take her apple.

The nurturing apple

Apples, the everyday fruit, can represent care and protection of a growing child. This metaphor has produced some charming portraits of young children, particularly by seventeenth century European painters. Take for example the painting of a unknown little Dutch boy by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout in which the sitter, nearly breaking out into a cheeky smile, brandishes an apple to the viewer. This painting echoes an etching made twenty years earlier by the painter’s mentor, Rembrandt, variously called Jacob caressing Benjamin or Abraham caressing Isaac, in which the father protects his precious apple-holding son. There is some conjecture that the boy in van den Eeckhout’s painting might be a member of the artist’s family, the apple signifying a good upbringing and familial love.

In a similar way, though much more formally, van Everdingen’s painting shows a Dutch boy’s christening resplendent with the sash and baptismal medal, and with doves in the background. He has taken a bite from the apple, indicating the partaking of knowledge, and the finch on his left hand, an easy bird to train, also alludes to education. This painting suggests that careful nurturing yields the best fruit.

When, from the same decade, a housewife holds an apple, it becomes a reference to the Virgin Mary, tending to the house. The birdcage and hearth in Gabriel Metsu’s painting also help tell a story of happy domesticity, the vine a probable reference to Psalm 128 “Thy wife shall be as a fruitful vine by the sides of thine house”.

This theme of apples being part of contented housework flows down the ages. Edward Davis was an accomplished painter of domestic interiors that often involve childhood instruction. In ‘Preparing for dinner’, by casting most of the picture in shadow, attention is focused upon the two girls, underlining the importance of teaching children to love and respect their elders, to be useful and obedient.

The apple of redemption

Coming full circle, the apple also represents overcoming original sin as well as the original temptation. With Mary as the new Eve, Jesus is the new Adam who takes away the sins of the world through allowing himself to be nailed to the cross to atone for the sins of Adam. Christ reaching for the apple symbolises the redemption of the world in this painting by a master of Bruges. David’s skill was bringing humanity to the traditional iconography of Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

And when Jesus holds the apple, it is the fruit of salvation. The extremely life-like south German statuette in The MET’s collection in New York stands triumphant at 15 inches tall. It is carved from a single piece of willow, finely painted. It would possibly be placed upon the altar at Christmas and been cared for by a religious order, as if a living child.

An apple for everyone

The apple is held by everyone. From lowly slum children playing with stones in a dark back alley in this dour painting by Manchester-born Thomas Armstrong, in which a girl holds a hoop in one hand and an apple in her other.

Through a more well-off though somewhat forlorn toddler standing in the garden amongst his toys, holding tightly onto his apple, in this painting by the troubled Ukrainian-born British post-impressionist Bernard Meninsky.

To royalty, where we’ll end with another fine small painting, this in the Royal Collection courtesy of His Majesty King Charles III. Here is Elisabeth, one of fifteen children of Charles II, Archduke of Austria. She is painted at the tender age of 1 year 5 months, resting her left hand on an apple – orb-like. It is not clear precisely what the significance of this pose was, but in German the royal orb is called Der Reichsapfel. Elizabeth died at eight years of age.

Apples everywhere. In this humble fruit dwells temptation, sensuality and beauty, as well as loyalty, nurturing and redemption. Apples are a gift, inextricably linked with people.

Thanks to:

- Hugh Fowler-Wright

- Anthony Mould

- Robin H Rodger, Documentation Officer, The Royal Scottish Academy

- Professor Timothy Wilson

Sources:

- Curators at all the art collections featured who have shared their knowledge

- Mijatovic (1874) Serbian Folk-lore

- Rossetti (1868) Venus Verticordia (For a Picture)

- Sanzsalazar (2020) Fruit of love: Van Dyck’s ‘James Stuart, Duke of Richmond’ in the Louvre and its afterlife in The Burlington Magazine

- Surtees (1971) The paintings and drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882): a catalogue raisonné

- Wilson (2016) Maiolica : Italian Renaissance ceramics in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Imitation Apples Apples have been modelled for centuries – for education, aesthetic, and sharing.

Imitation Apples Apples have been modelled for centuries – for education, aesthetic, and sharing. Paul Cézanne - Still Life with Apples, circa 1878, oil on canvas. Copyright © The Provost and Fellows of King's College, Cambridge, UK

Paul Cézanne - Still Life with Apples, circa 1878, oil on canvas. Copyright © The Provost and Fellows of King's College, Cambridge, UK