Antonovka – The People’s Apple

The hardy Antonovka apple holds a special place in Russian culture and cuisine.

Apples are often powerful symbols of ancient properties: health, afterlife, prosperity, knowledge. And sometimes an apple becomes a symbol of something much more recent and more local. A life that no longer exists – the good old days.

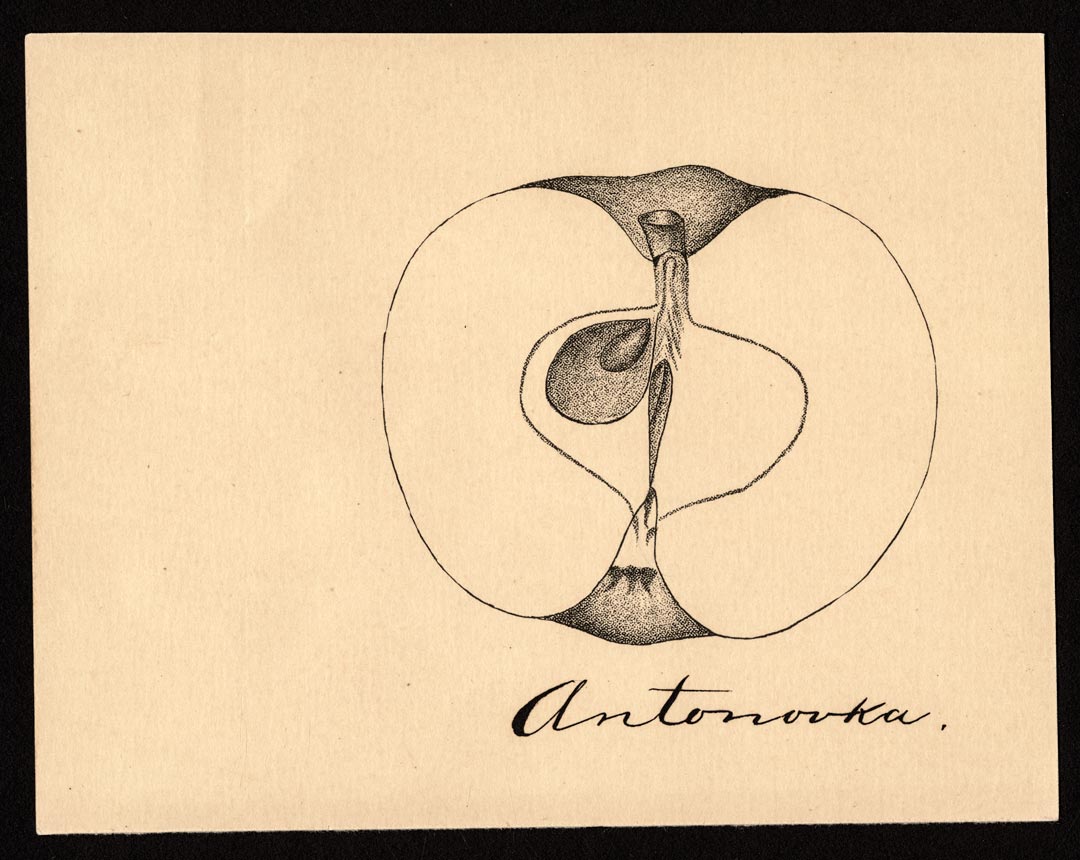

The Antonovka apple was first noted, probably as a random wild seedling, in Kursk, western Russia, in around 1826. The common Antonovka is a large yellow-skinned apple with soft. mealy flesh and strong aroma. Kursk takes pride in being the birthplace of Russia’s most important apple.

Later, in 1888, an improved cultivar Antonovka polutorafuntovaya was formalised by Ivan Vladimirovich Michurin, the important Russian horticulturalist and plant breeder, at Tambov Oblast. Michurin, a contemporary of Vavilov, went on to introduce other Antonovka cross varieties.

The Antonovka’s main characteristic is its hardiness. It grows well and flourishes in northern climates, and is an important cold-hardy rootstock. Antonovka is dominant in Russia where it has come to hold a very special place in people’s hearts.

There are two reasons for this.

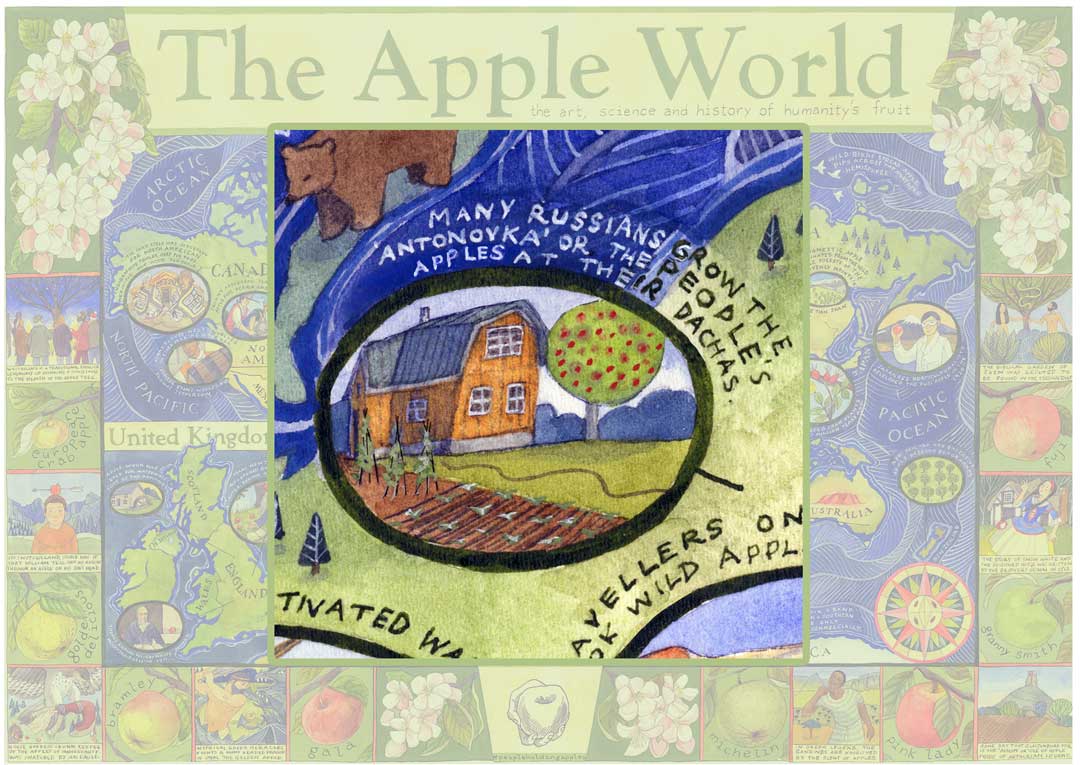

Since the nineteenth century, city dwellers in Russia have also had their country dachas. A dacha was originally a plot of land given (from which the word dacha comes) to his courtiers by Peter the Great, so that when they left town they wouldn’t go to country estates unreachably far away. During the nineteenth century, a piece of land in the country – most often not that far from the city – became a thing that most middle-class people would have. Although these were sometimes country estates, they were more often little more than allotments with a hut big enough to spend the occasional night in – a weekend refuge from the city. During Soviet times, these dachas were given out by the state. And on a great many of these pieces of ground, people planted Antonovka apple trees, so that the Antonovka became known as the People’s Apple.

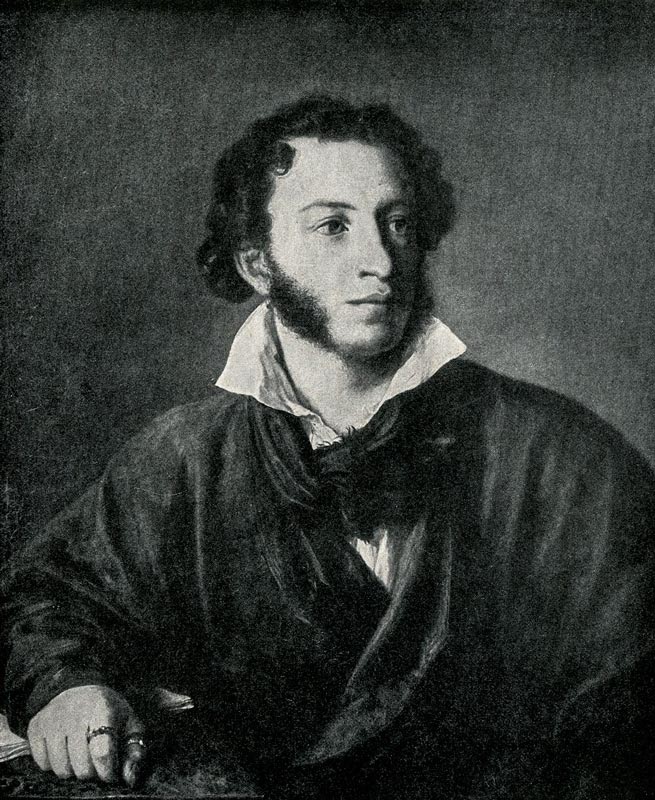

Either because of this, or the other way around, the Antonovka apple became embedded in traditional cuisine – a taste redolent of home. Its texture made it very good for pickling, and pickled apples became, for some people including famously the poet Pushkin, a trigger which summoned and represented the good old days. The days of traditional life, when everything was good and certain. Apparently, Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin couldn’t get enough pickled apples.

“Once forbidden fruit is seen, no paradise can stay serene”

From ‘Eugene Onegin’ by Pushkin

Pushkin’s friend Prince Pyota Andreyevich Viazemsky writes that Pushkin was no gourmand. He did not know much about the art of cooking but could be greedy. He describes Pushkin’s love of ‘mochenye iabloki’. Literally, these were ‘soaked’ or ‘macerated apples’, preserved in this way in wooden barrels with sugar or salt and sometimes both.

Also, because it’s not too sweet, the apple is widely used in pies and apple wine.

The People’s Apple was also the basis for a kind of sweet that seems often to be described as “not marshmallow”. Called Pastila, it’s been made in various forms for hundreds of years and is eaten to accompany coffee or tea. Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya, Tolstoy’s wife, was a fan and left a recipe in her notebooks.

Beaten egg white, sugar and pureed apples – Antonovka apples – slowly baked.

Chekhov in his 1880 story, The Little Apples, mentions Antonovka apples that somebody might give as a present in the following autumn to thank the narrator for not having mentioned his surname in print. And then in 1900, Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin wrote a short story named ‘Antonovka Apples’. This is basically an ode to a departed way of life – that of the landed gentry of the nineteenth century.

“The aroma of Antonovkas is disappearing from estates and country houses. We lived those days not long ago, and yet it seems a hundred years have passed since then.”

From ‘Antonovka Apples’ by Bunin

The Antonovka has become an echo of times past. A fruit loaded with memory, myth, and nostalgia for a world that never quite was.

Pushkin died on 10th February 1837, at the age of thirty-seven, from injuries sustained from a needless pistol duel. Russia grieved the loss of perhaps its greatest, and most apple-greedy, poet.

Today, the honeyed fragrance of Antonovka apples and sweet delight of pastila is again swallowed in melancholy by senseless aggression.

Sources:

- Bunin (1900) Antonovka Apples

- Possamai (2017) Ivan Bunin. The Scent of Apples and Memory in Perfume and Literature -The Persistence of the Ephemera edited Forza and Francescato

- Pushkin (1833) Eugene Onegin translated by Charles Johnston published in 1979 by Penguin Classics

- Viazemsky (1883) Complete Works Polnoe sobranie sochinenii Volume 8

Payne Limner - Alexander Spotswood Payne and His Brother John Robert Dandridge Payne, with Their Nurse 1790-91 © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA. Gift of Miss Dorothy Payne. Photo Katherine Wetzel.

Payne Limner - Alexander Spotswood Payne and His Brother John Robert Dandridge Payne, with Their Nurse 1790-91 © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA. Gift of Miss Dorothy Payne. Photo Katherine Wetzel. Grafting: Giving Nature a Helping Hand

Grafting: Giving Nature a Helping Hand