Apples for the Wealthy

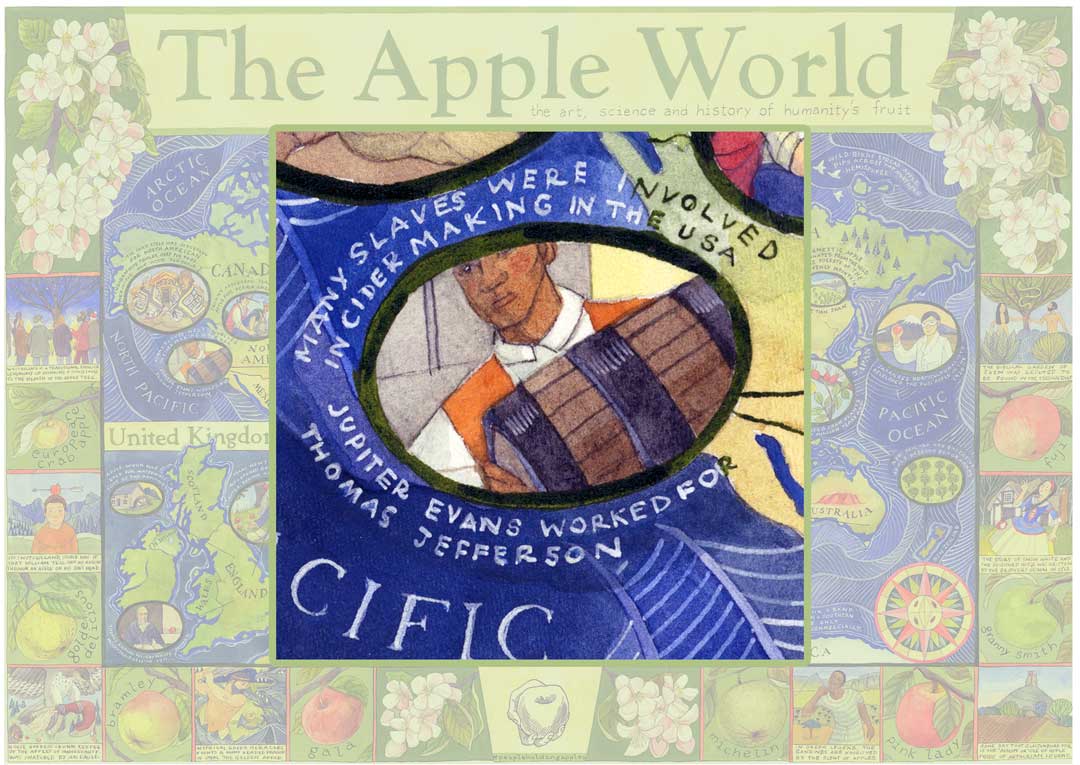

In nineteenth century America, enslaved people grew apples for wealthy landowners, and perfected fine ciders for them to drink.

Early nineteenth century Americans drank copious quantities of alcohol, particularly cider. In what was then a largely agricultural economy, apples were grown across the young nation. Whilst Johnny Appleseed (1774-1845) eked out his peripatetic existence with seedling apple nurseries across Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana to supply frontier settlers, further south at Monticello, near Charlottesville in Albemarle County, Virginia, his contemporary Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) inherited a 5,000 acre estate. Jefferson, who was to become third President of the United States, significantly improved the estate, overseeing the construction of a big house, gardens, and orchards.

Like Appleseed, Jefferson was interested in apples. But Jefferson was particular, he had his favourite varieties. For example, when he was Minister to France, he complained that the French had no apple to compare to the American Newtown Pippin.

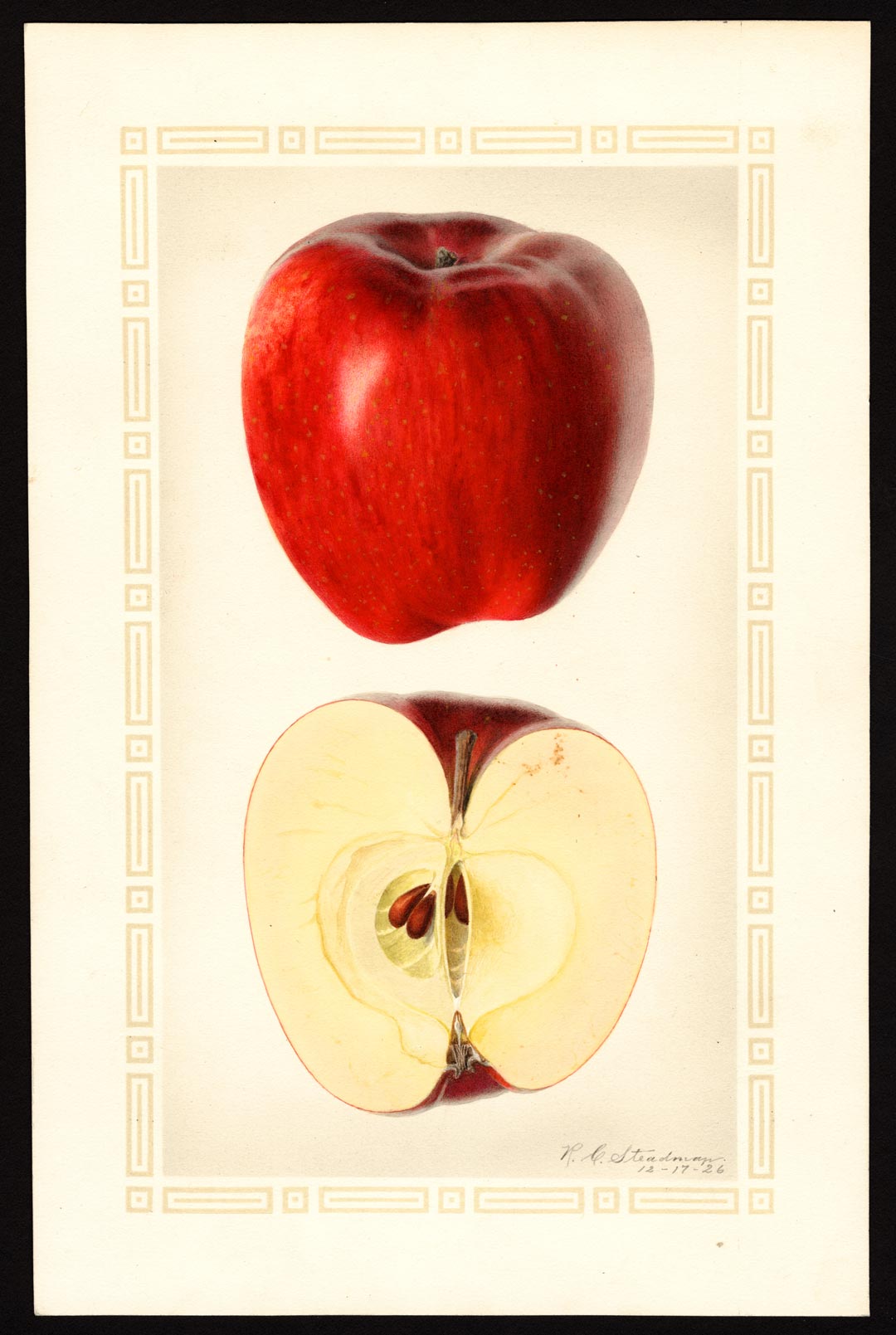

His well-tended orchards were a statement of refinement and were meticulously planned and painstakingly recorded in a Garden Book. A total of eighteen apple varieties were cultivated, and there were at least two nurseries for propagation. Monticello’s South Orchard contained dessert apple trees mainly grafted with two New York varieties, Esopus Spitzenburg and Newtown Pippin (which is also known as the Albemarle Pippin because it grew so well in Albemarle County). These were considered the best American table apples at the time, Coxe singling them out for admiration in his 1817 book on fruit trees because of their “exquisite flavour”.

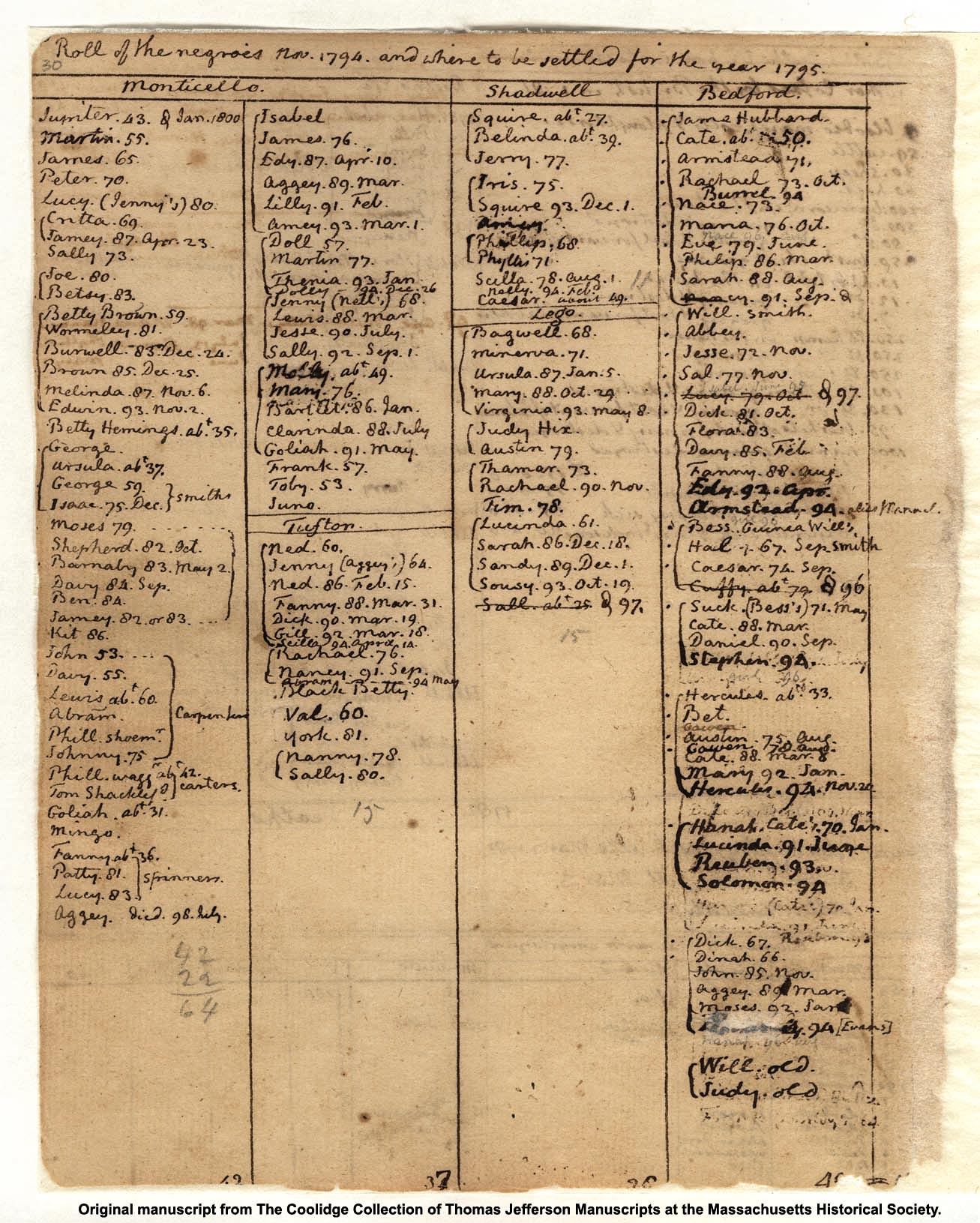

However, Jefferson’s vision for Monticello was only realised through the toil of slaves of African descent. It is estimated that some 400 enslaved people worked in the house, gardens, and farm during Jefferson’s lifetime. Even by 1860, more than half the population of Albemarle County was enslaved and nearly a third of the population of Virginia – 490,865 people – were slaves.

One of the slaves at Monticello, Jupiter Evans (1743-1800), was given to Jefferson when they were both twenty-one years of age. He was an invaluable part of Jefferson’s household for the rest of his life, including being his coachman.

Grafted trees required more care than seedlings and were more expensive to purchase. In contrast to what would be found at Monticello, seedling trees that are raised from pips will grow haphazard trees and lead to untidy-looking orchards, often with apples of poor quality fit for nothing more than rough hard cider and applejack. However, the seedling orchards, widespread across the nation, were essential to the development of America’s rich apple stock because they proffered an occasional treasure – an apple with exceptional attributes worthy of preservation as a grafted cultivar. Indeed, the apple varieties Jefferson cherished at Monticello were originally from chance American seedlings.

Around this time, these different types of apple became tokens of socio-political identity. Nurseryman John Goldthwait supplied grafted trees to Ohio settlers in the early nineteenth century. Ironically, he is reported as comparing a poor seedling to Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party, which supported the interests of the simple yeoman farmer. He contrasted the seedling with a tree in his orchard of grafted cultivars – an improvement-minded Federalist, like he was. Seedlings stood for the unambitious and idle, grafted trees for progress and high standards.

“As cultural symbols, the grafted and seedling apple tree were crude stereotypes. But they nonetheless had resonance in the early nineteenth century.”

William Kerrigan

Conversely others, notably Henry David Thoreau, celebrated the seedling’s strength and diversity that “emulates man’s independence and enterprise” and offers “more racy and wild American flavors”. Grafted cultivars he found bland by comparison, “tame and forgettable.”

The ubiquitous apple, adaptable to different conditions across the nation, led Virginian James Fitz to observe in 1872 that “The apple is, so to speak, our democratic fruit…that is cultivated all over the country”.

“The apple in America became a parable.”

Michael Pollan

Noting that imported English varieties suffered in the American climate, Emeritus Director of Gardens and Grounds at Monticello Peter Hatch suggests that, through selection and grafting of the best seedlings that flourished locally, “the development of regional apple varieties was essentially a rural, populist movement”. And for Jefferson, who was fairly obsessed with proving to the English and French that the American climate and soils were not somehow defective and inferior to Europe’s, developing fine fruit was one way to do that, countering the theory that European crops degenerated when grown in America.

“The natural world of America became a symbol for its political and cultural significance – or insignificance, depending upon your point of view.”

Andrea Wulf

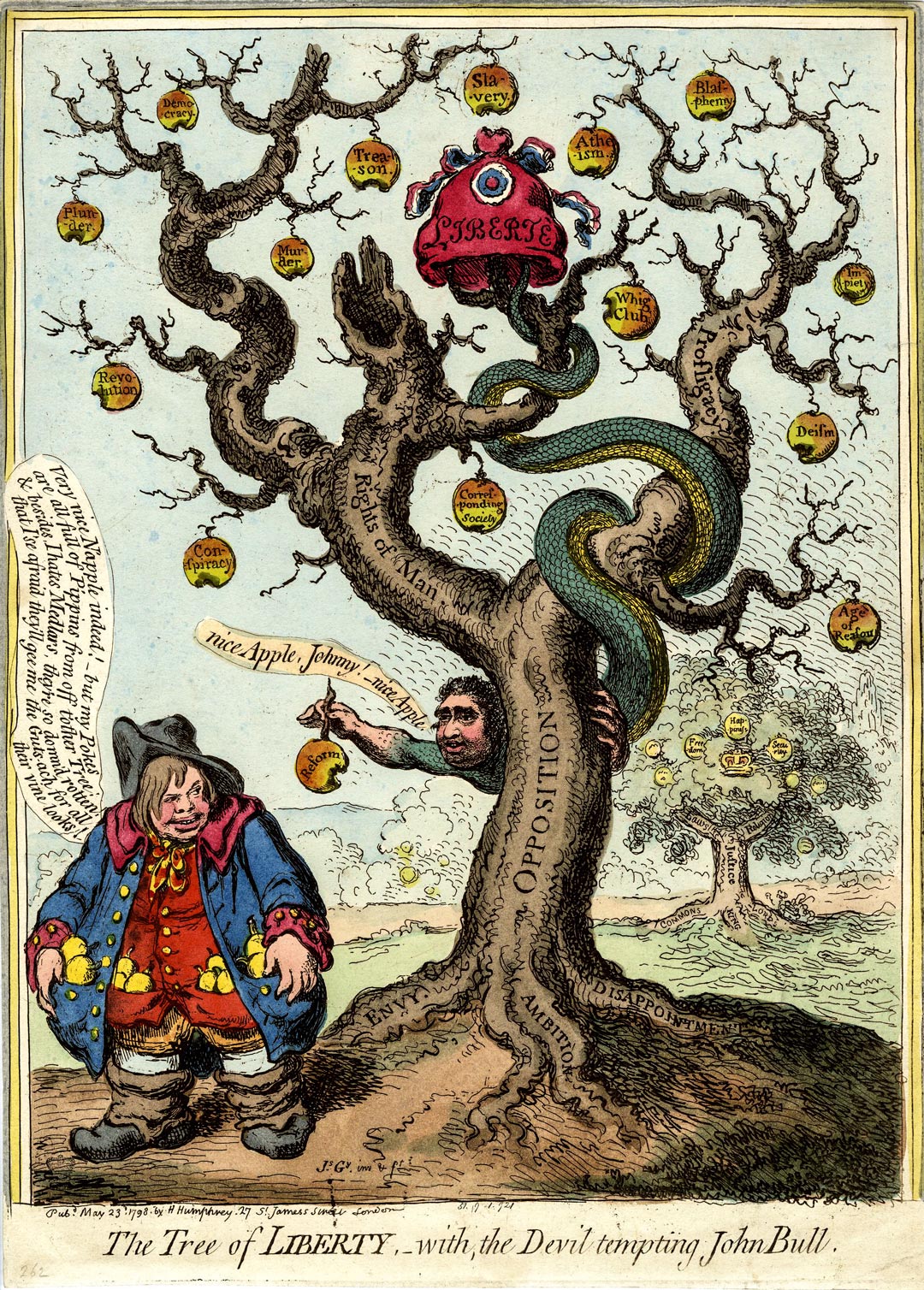

Meanwhile over in England, against the backdrop of revolution in France, an etching of 1798 also shows the fruit of good trees and bad. The UK’s Whig party is displayed in a decaying Tree of Liberty, rooted in self-interest, in which hang rotten fruit inscribed with the political and religious evils of the time, including ‘Slavery’. The Whig politician Charles James Fox tempts John Bull with a damaged apple inscribed ‘Reform’.

John Bull is not interested, his pockets full of golden apples. A thriving tree in full leaf in the background bears the insignia of the establishment – including pippins inscribed freedom, happiness, and security.

“Very nice N’apple indeed! – but my Poke are all full of Pippins from off t’other Tree”

The making of ‘fine cyder’ was also important at Monticello, as shown in farm and household consumption records. Surviving correspondence proves that Jefferson took a keen interest in its making in October and November and its bottling in March.

As later recalled by Captain Edmund Bacon, who was overseer at Monticello from 1806,

“Then every March we had to bottle all his cider. Dear me, this was a job. It took us two weeks. Mr. Jefferson was very particular about his cider. He gave me instructions to have every apple cleaned perfectly clean when it was made.”

Jefferson’s instructions for apples harvested from North Orchard in 1817 indeed show the care that he insisted upon, “let them be made clean one by one, and all the rotten ones thrown away or the rot cut out. nothing else can ensure fine cyder.”

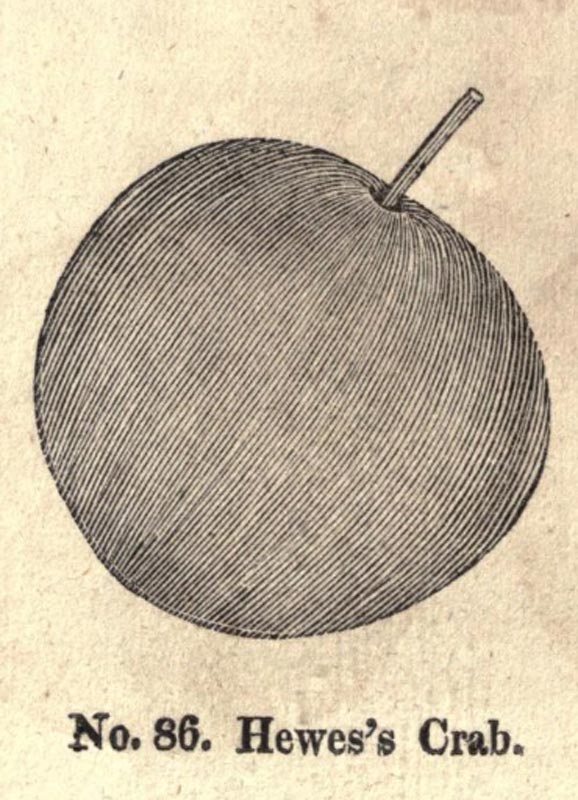

In contrast to a homesteaders’ random seedling trees, the 265 cider apple trees which were planted in Monticello’s North Orchard were mainly just two varieties – Virginia Hewe’s Crab and Taliaferro. Jefferson’s taste for cider was discriminating, he considered Taliaferro (“Toliver”) cider to be the finest “it has more body, is less acid, and comes nearer to the silky Champaigne than any other” he wrote to Philadelphia horticulturalist James Mease in 1814.

Although records about enslaved workers are sketchy, Jupiter appears to have supervised the bottling of cider. Enslaved overseer George Granger had knowledge of apples having both worked in the orchards and been heavily involved with the cidermaking process. George’s wife Ursula also bottled cider and there were undoubtedly others involved. These slaves will have developed great skills that were relied upon to make and store the excellent cider.

The circumstances of Jupiter’s death are described in a letter from Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Randolph, to Jefferson on 30th January 1800 although, tellingly, the precise date of his death is not recorded. It is thought to have been about two weeks before. In response, Jefferson wrote to his son-in-law,

“I am sorry for him as well as sensible he leaves a void in my domestic administration which I cannot fill up.—I must get Martha or yourself to give orders for bottling the cyder in the proper season in March.”

The contribution of African Americans to the development of esteemed orchards and fine cider in the United States went largely unrecorded.

“While the plantation owner generally would get the credit for the products and processes that were developed on his plantation – these techniques and the outcome would not have happened without the labor and contributions of the enslaved people – maintaining the orchards, harvesting the apples, processing the cider. The names of many of these individuals are currently lost to written histories – in fact they were invisible as individual people to their overseers and so to history. The details of their lives may not ever be known due to scant recordkeeping.”

Mary C Lauderdale, Black History Museum

It is only because the estate records and correspondence of Jefferson, as one of America’s Founding Fathers, have been well preserved that we know a little bit about the skills of Jupiter Evans and the Grangers.

Not only that, but the skills that enslaved workers developed in service of the great Southern households evaporated during the nineteenth century. Following emancipation, newly freed slaves may not have had the inclination nor the resources to continue to make cider. Nor did American cidermaking fit easily with wider demographic and economic changes from concentrated industrialisation, urbanisation, and eastern European immigration that favoured beer and spirits. By the mid nineteenth century, US cider consumption had fallen to negligible quantities and 1920s Prohibition was the final straw. The skills were largely lost.

In much the same way, Jefferson’s favoured Taliaferro apple has disappeared in Virginia. Being imprecisely recorded at the time, it is probably lost despite the best detective efforts of a retired Alabama judge to trace it.

“There always seems to be a new and promising candidate on the scene. In that way, the Taliaferro lives on as surely as, say, the holy grail or Excalibur. Perhaps it is even more valuable to have one particularly precious variety—some lost remnant of Eden, a golden apple of the sun—that is always just out of reach than it is actually to find it.”

Judge Susan Walker

Perhaps, too, the fact that we know so little about the enslaved people who grew apples for the wealthy, and perfected fine ciders for them to drink, brings power to their legacy.

“Thankfully, the written story is not set in stone – as the smallest nuggets of information are uncovered in the future, they will aid in telling a more complete history.”

Mary C Lauderdale, Black History Museum

About Jupiter’s Legacy

Jupiter’s Legacy acknowledges the complexity of nineteenth century Virginian society and honours Jupiter Evans as representative of those who were a crucial part of the cider process at Monticello but had been somewhat ignored. Jupiter’s Legacy is the flagship cider of Albemarle CiderWorks, a blend of some 20 to 30 varieties of apples grown in their orchard.

Like Monticello, Albemarle CiderWorks is based in Albemarle County, Virginia. It has been operating for 14 years, making it Virginia’s oldest modern cidery and part of a resurgence in hard cider across the USA. Their ‘Virginia Hewes Crab’ cider was awarded Best in Show Cider in the 2022 Virginia Governor’s Cup®.

Sources:

- Pierson (1862) Jefferson at Monticello

- Coxe (1817) A view of the cultivation of Fruit Trees and the management of Orchards and Cider

- Fitz (1872) The Southern Apple and Peach Culturalist

- Founders Online – Correspondence and other writings of seven major shapers of the United States

- Hatch (1998) The fruits and fruit trees of Monticello

- Janik (2011) Apple. A Global History

- Kerrigan (2012) Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard

- Massachusetts Historical Society – The Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts

- Pollan (2003) The Botany of Desire

- Pucci and Cavallo (2021) American Cider

- Reiss (2015) Apple

- Rorabaugh (1979) The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition

- Scott (1877) A complete history of Fairfield County, Ohio

- Stanton (2012) ‘Those who labor for my happiness’: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

- Thoreau (1862) Wild Apples

- Wulf (2016) Thomas Jefferson’s quest to prove America’s natural superiority in The Atlantic

Thanks to:

- Brian Alberts, beer historian

- Peter Hatch, Emeritus Director of Gardens and Grounds, Monticello, Virginia, USA

- Darlene Hayes, editor of Malus

- Professor William Kerrigan, Muskingum University, Ohio, USA

- Mary Lauderdale, Director of Collections, Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia, USA

- Michelle McGrath, Executive Director, American Cider Association

- Howell Perkins, Image Rights Licensing Coordinator, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA

- Charlotte Shelton, Owner, Albemarle CiderWorks

- Lucia Stanton, Senior Historian Emerita, Monticello, Virginia, USA

- Judge Susan Walker, retired Alabama Judge and apple hunter

- Andrea Wulf, Historian and Author

Crispin van den Broeck - Two young men c1590 © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

Crispin van den Broeck - Two young men c1590 © The Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge Henry G Van Deman - Antonovka 1886 U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705

Henry G Van Deman - Antonovka 1886 U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705