Avalon: The Isle of Apples

The apples of Celtic legend and a foundation myth for Britain

The story of Avalon is one of ancient myth, Celtic legend, and medieval marketing. Particularly where Glastonbury is involved, it’s very hard to disentangle the many claims, interpretations, and wishful readings.

Avalon is the Isle of Apples, the name coming from the Welsh for apple or apple tree. Here, as elsewhere in the world, apples represent long life, fruitfulness, and health and are often magical. The apple is an important tree to Druids, whose wand would be made of yew or apple wood.

The Isle of Apples is a part of, or certainly an entrance to, the Celtic Otherworld (Annwn). There are a great many Celtic stories in which a character enters this Otherworld, often needing a key to enter, that key being the branch of an apple tree. Entrances to the Otherworld are often in howes (burial mounds) or across water – a lake, or the western sea; the west being the direction of decline, death, and the afterlife. But the Otherworld is not simply a place you go after death; it exists alongside our own world. To enter it is not necessarily a one-way journey. In the English medieval ballad, Thomas the Rhymer, Thomas must choose between three roads, the narrow road to heaven, the broad road to hell and the middle road to the land of Elfland – or Avalon.

Tales of the legendary place known as Avalon may have been told for two thousand years or more, but nobody could tell you where it was, and there was no single way of getting there….

Until the twelfth century.

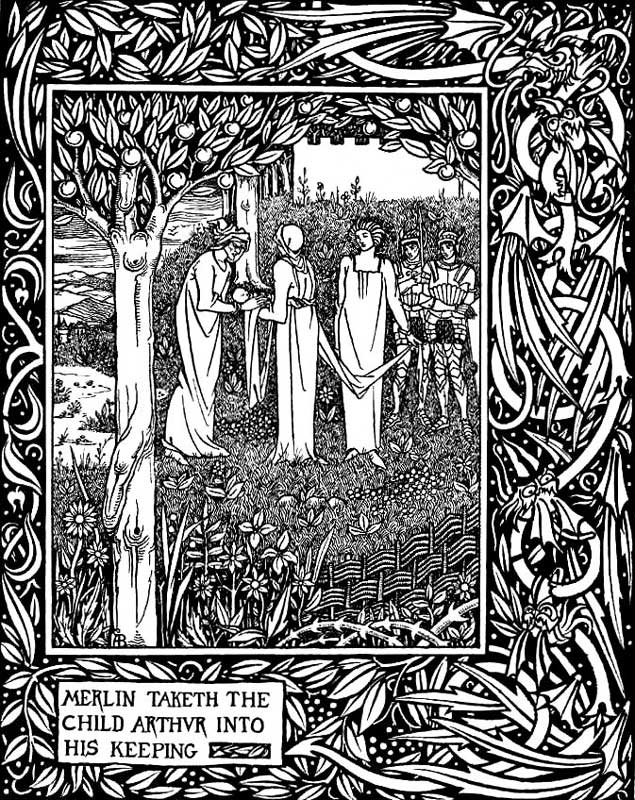

Two books written by Geoffrey of Monmouth, a British bishop born in the Welsh town less than twenty miles south of Hereford, established the story of King Arthur and Avalon. His Vita Merlini, The Life of Merlin, established the apple provenance of Avalon:

“The Island of Apples gets its name ‘The Fortunate Island’ from the fact that it produces all manner of plants spontaneously. It needs no farmers to plough the fields. There is no cultivation of the land at all beyond that which is Nature’s work. It produces crops in abundance and grapes without help; and apple trees spring up from the short grass in its woods. All plants, not merely grass alone, grow spontaneously; and men live a hundred years or more.”

In Geoffrey’s Historia regum Britanniae, the History of the Kings of Britain, King Arthur is portrayed as an apparently authentic historical character. After the last great battle at Camlann, Arthur is taken to Avalon (whence came his sword, Excalibur) to recover. Although controversial even in the Middle Ages, the book was an international best seller and gave birth to the compelling cult of King Arthur. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s creative genius formed the basis of Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur three hundred years later which in turn inspired Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem The Passing of Arthur in his Idylls of the King another five hundred years after that.

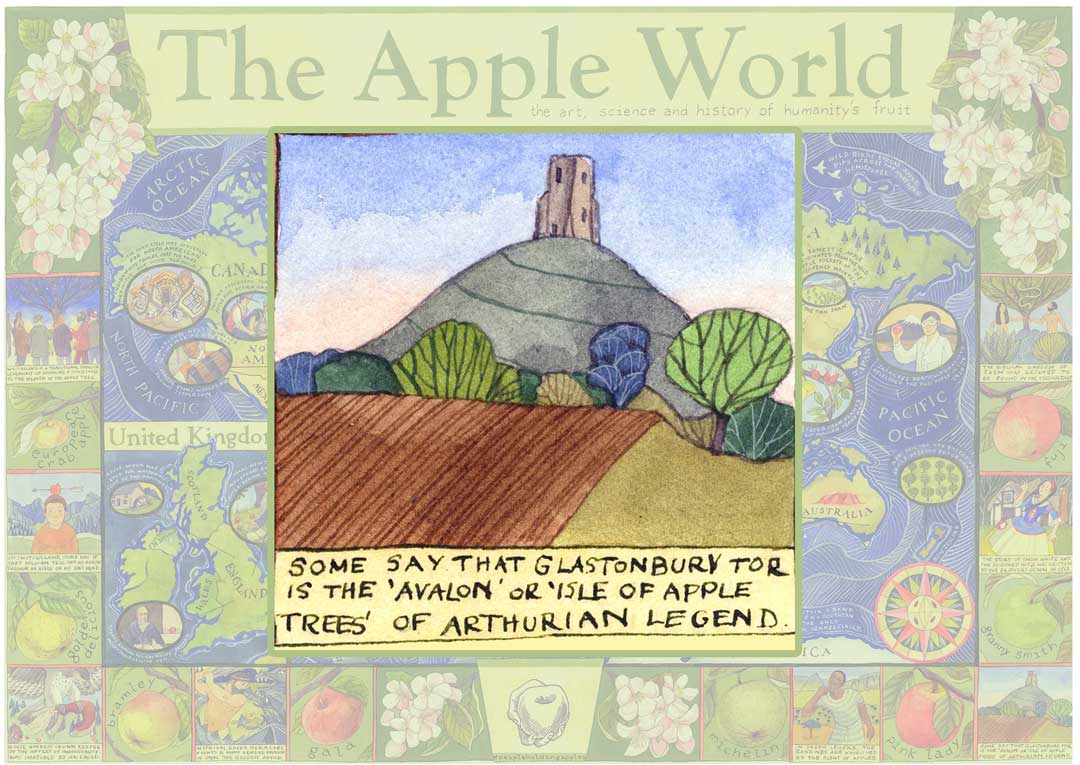

In 1184 the mighty Glastonbury Abbey was nearly destroyed in a fire. During the rebuilding work that followed, the monks conveniently discovered the tombs of Arthur and his queen Guinevere. Few people really believed them but, all the same, Glastonbury became a site of pilgrimage for those wanting to admire and pay homage at the tomb of the great king and his beautiful queen – not just figures of legend, but real people, as proved by their graves. And, of course, it was plain that Glastonbury must be the mystical Avalon.

It was not so very unlikely. In those days, Glastonbury lay in the middle of the marshland of the Somerset Levels. It would have been a mysterious and hard-to-reach place, surrounded by water and treacherous pathways. So it made perfect sense that, all that time ago, the wounded Arthur had been taken in a boat of glass to this place – to Avalon – to be nursed until the day when he was needed once again to save his country. Rex quondam, rexque futurus, as Malory puts it – the Once and Future King.

Glass – or crystal – is mentioned often in Celtic legend in association with the Otherworld, which is why Arthur’s boat is made of glass. You can see how a back-formation of the name Glastonbury, to call it the Isle of Glass, is an appealing idea. It’s unlikely, though. More probably, it comes from a Celtic word for the woad plant, later mistranslated as “glass”.

Whether or not Avalon is a real place in Somerset, in all this misty soup, the one and most important constant is the apple, and the magical, health-giving, fortune-bringing properties of the apple tree and the apple fruit.

“To the island- valley of Avilion,

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly, but it lies

Deep meadow’d, happy, fair with orchard lawns

And bowery hollows crowned with summer sea,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.”

From The Passing of Arthur by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Sources:

- Dumville (2011) Celtic Visions of England, in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture, ed. by Andrew Galloway

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (c1149) The Life of Merlin translated by Basil Clarke (1973)

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1859) Idylls of the King

- Clas Merdin: Tales from the Enchanted Island by Edward Watson

- Avalon by Prof. Geller on Mythology.net

Thanks to:

- Ian Lewis who researched and wrote this story for Apples & People

- Dr James Simpson, Reader in French, University of Glasgow

The Gangines of the Mappa Mundi

The Gangines of the Mappa Mundi Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man c.1615, oil on panel, Mauritshuis, The Hague

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder - The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man c.1615, oil on panel, Mauritshuis, The Hague