Our Crab Apple Mothers

Recollections of three women connected through a poem

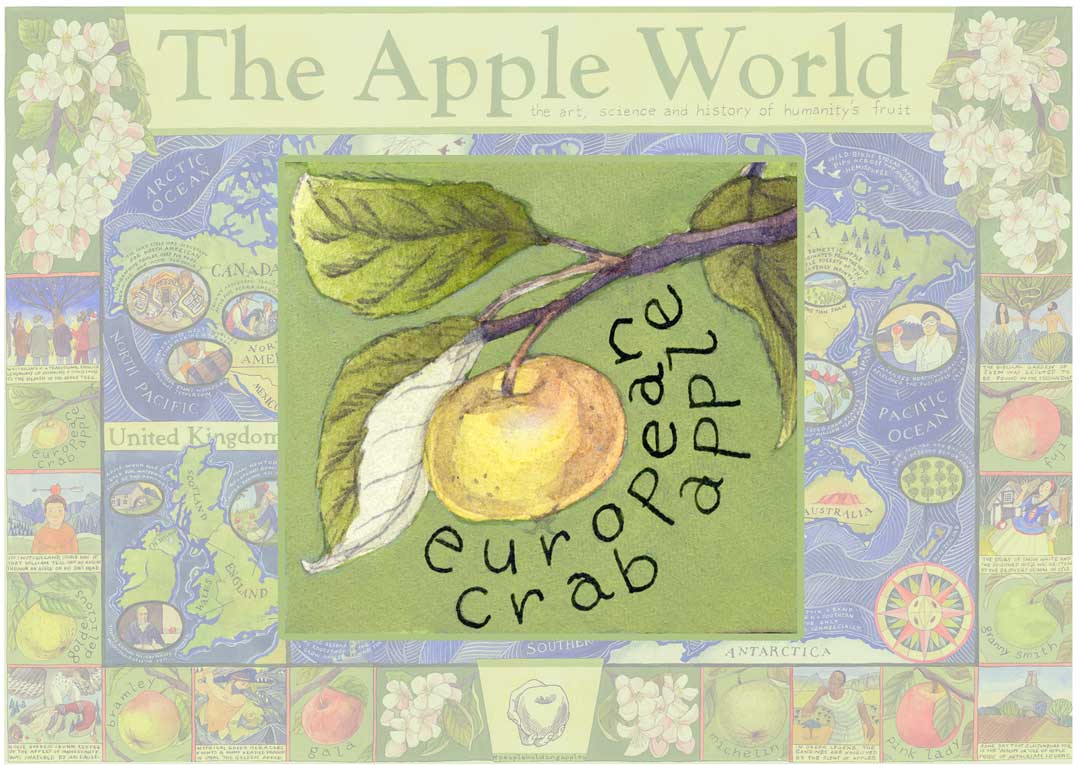

The European Crab Apple Malus sylvestris, the wild ‘forest apple’, is a symbol of fertility. It has grown wild across Europe since the Ice Age, generally solitary trees that are resilient to adversity and can grow in the most hostile terrain. They offer splendid blossom in springtime and food for birds and animals.

Evidence shows that humans have also eaten the bitter fruits, cooked or dried, since Neolithic times some four thousand years ago. The Celts appreciated the Crab Apple well before the introduction of the domestic apple into Western Europe by the Romans, and later records show Crab Apples used for juice and vinegar and for pig fodder, the wood from the trees for timber.

“In modern times, the ‘Crab Apple’ has maintained a tenuous place in the public consciousness because of its use in setting jams and making apple jellies”

Worrell, Ruhsan and Renny in Discovering Britain’s Truly Wild Apples 2021

Malus sylvestris cross-pollinated with the Tian Shan’s Malus sieversii, brought westwards by ancient travellers. It is therefore partly responsible for shaping the characteristics of the domestic apple today eaten the world over, its ‘part-parent’ so to speak.

For this story, Vicki Feaver has kindly shared her poem Crab Apple Jelly. The poem recollects her mother’s annual ritual harvesting and processing Crab Apples. It is read by Abigail McKern and illustrated by Emily Feaver. This poem prompted exploration of three women’s personal recollections of their mothers and Crab Apples.

Abigail McKern reading Crab Apple Jelly by Vicki Feaver from her collection of poems ‘The Handless Maiden’

Crab Apple Jelly

Every year you said it wasn’t worth the trouble –

you’d better things to do with your time –

and it made you furious when the jars

were sold at the church fête

for less than the cost of the sugar.

And every year you drove into the lanes

around Calverton to search

for the wild trees whose apples

looked as red and as sweet as cherries,

and tasted sharper than gooseberries.

You cooked them in the wide copper pan

grandma brought with her from Wigan,

smashing them against the sides

with a long wooden spoon to split

the skins, straining the pulp

through an old muslin nappy.

It hung for days, tied with a string

to the kitchen steps, dripping

into a bowl on the floor –

brown-stained, horrible,

a head in a bag, a pouch

of sourness, of all that went wrong

in that house of women. The last drops

you wrung out with your hands;

then, closing doors and windows

to shut out the clamouring wasps,

you boiled up the juice with sugar,

dribbling the syrup onto a cold plate

until it set to a glaze,

filling the heated jars.

When they were cool

you held one up to the light

to see if the jelly had cleared.

Oh Mummy, it was as clear and shining

as stained glass and the colour of fire.

Vicki Feaver in The Handless Maiden © Jonathan Cape 1994

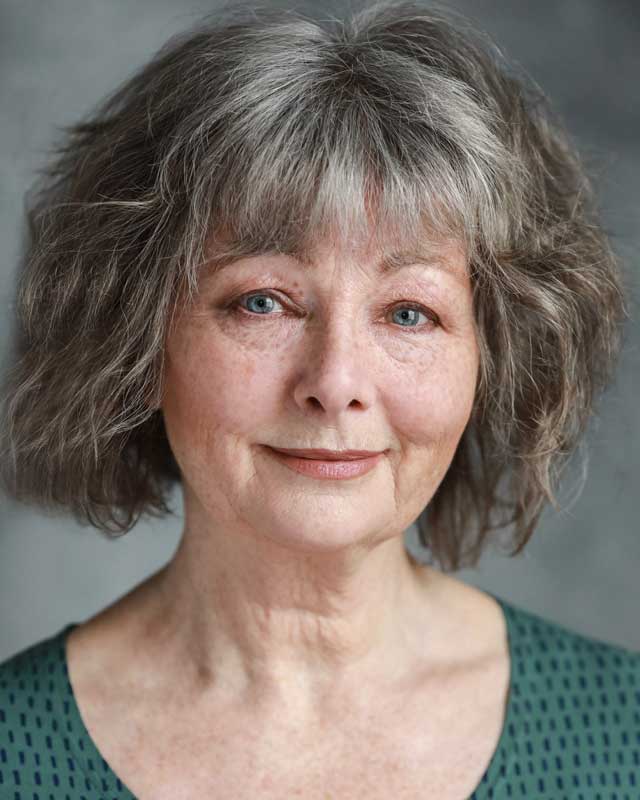

The reader – Abigail McKern

An award-winning Royal Shakespeare Company actress, Abigail serendipitously contacted Apples & People about the poetry reading that she had been offering during lockdown. Abigail was commissioned by Apples & People to read the poem. It turned out that Crab Apples featured in Abigail’s memories of her mother.

“The Crab Apple tree has always had a special place in my heart – a fond memory from my childhood. When I was five we were lucky enough to live in a beautiful double fronted Victorian house (sadly destroyed in the 1970’s to make way for flats). It came with half an acre of garden that seemed unending and full of secrets to my young imagination.

My mother was totally disinterested in cooking although she always managed to put simple, wholesome meals on the table every day. She had been a successful actress in Australia and I think found being a ‘stay at home Mum’ in the sixties pretty boring. However, she never complained and was always inventing ‘projects’ to keep her inspired and busy.

In our front garden was a huge Crab Apple tree and one year she decided to make Crab Apple jelly – a rather arduous and complicated process I seem to remember! I was absolutely captivated when she held the finished jelly jars up to the sun by the kitchen window. The most magical golden colour and SO delicious on warm toast.

She only made it that one time (she got bored quickly) but her passion for trees never faltered. After reading Silent Spring by Rachel Carson she became a dedicated organic vegetarian, which must have done her some good because she lived to be nearly one hundred years old.

She always refused to have her photograph taken unless there was an interesting tree in the background and during a terrible summer drought in the 1970’s she used to carry heavy watering cans from her house onto the village green where there was a struggling tree. She saved it and it’s still there today.

My mother died of COVID at the beginning of 2021 and I have recently planted a Crab Apple tree in her memory. There is nothing more fitting for her – she would have been delighted.”

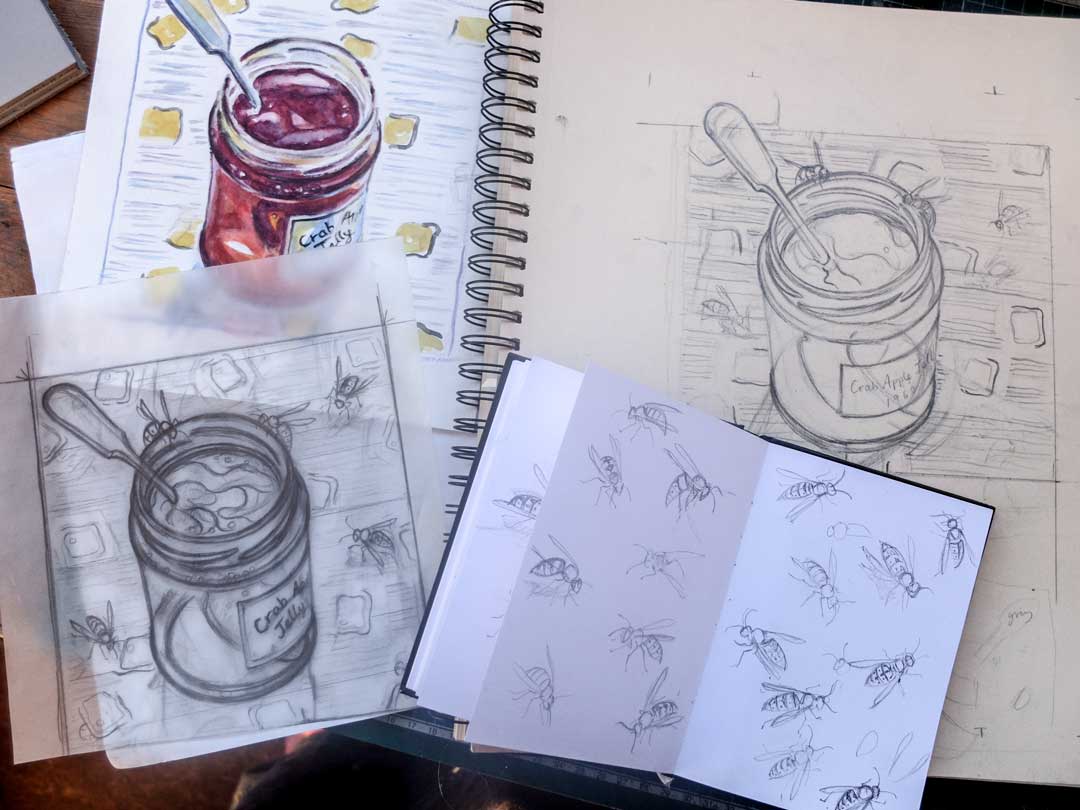

The artist – Emily Feaver

Emily Feaver is a professional artist. Early in her career she illustrated the Crab Apple Jelly poem for her mother, Vicki. Apples & People originally contacted Emily to reach her mother but subsequently commissioned Emily to create a new linocut. Her printed image brilliantly depicts the vibrancy of the jelly remembered by her mother.

“Thirty years ago my mother and I collaborated on a small pamphlet of her poems, the cover was bright red and the title ‘Crab Apple Jelly 1992’ was glued on like a label on a jar. I illustrated the poem of the title with a small black and white image of ‘clamouring’ wasps – it was an early linocut and embarrassingly clumsy. It was a welcome challenge therefore, when it was suggested by the Museum of Cider that I revisit the poem for the exhibition programme Apples and People, to coincide with Mothers Day 2022. Echoes of my crotchety jelly-making grandmother came to me as I laboured away, grumbling at my slow, painstaking progress.

I saw parallels with my mother too – her poetry writing often involves obsessive reworking and ruthless editing in the search for clarity. My grandmother, my mother and I, all three of us have taken on the task of transforming the ‘bitter’ raw material ; the Crab Apple / the childhood memory/ the slabs of grey Lino – into something other – something palatable, something good. When it came to the illustration, I was drawn, rather like the wasps and child /mother of the poem, towards the final image of sweet, clear, shining jelly, like ‘stained glass – and the colour of fire’.

Thirty years on I’m still not sure that I have done justice to my mother’s poem. I am in awe of her ability to create something beautiful, powerful, resonant and clear, out of the visceral, the difficult, the domestic and the mundane – to tackle so succinctly the emotions and tensions most of us are loath to admit.”

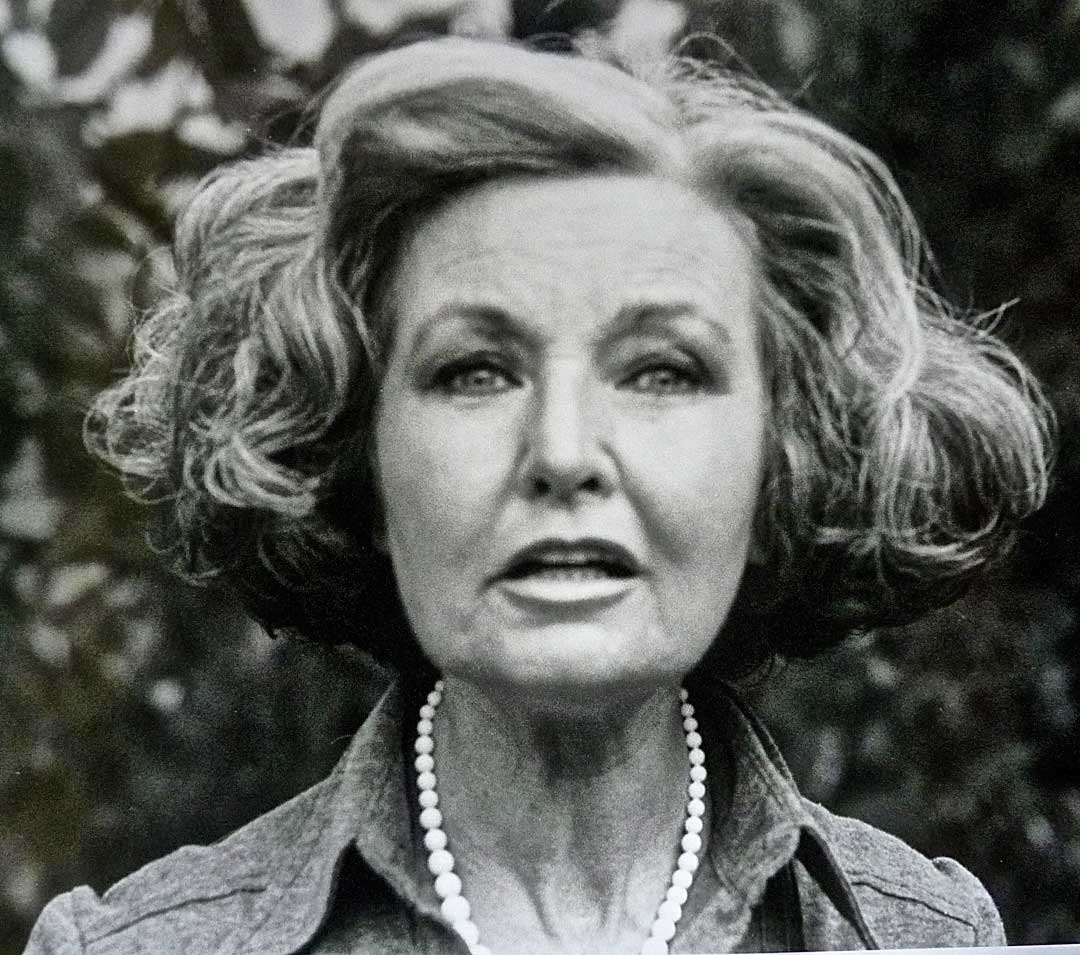

The poet – Vicki Feaver

“An exercise I often set students is to write a poem describing someone doing or making something. Seamus Heaney’s poem ‘Digging’ is a good example. He likens the way he ‘digs’ with his pen to his father digging with his spade to lift new potatoes and his grandfather cutting peat. Setting myself the same exercise, I wrote about my vivid memories of my mother making Crab Apple jelly.

Every poem I write is a voyage of discovery and ‘Crab Apple Jelly’ was no exception. I didn’t realise when I set out to write it that the bag of apple pulp (‘a head in a bag, a bag of sourness, of all that went wrong in that house of women’) would contain the grief and anger that I found so upsetting as a child. The grief was for my Uncle Jack, my mother’s younger brother who was killed fighting in Burma at the end of World War II. The anger was between my mother and her mother who lived with us, both strong women who had to share a kitchen.

My mother was an amazing woman. As well as teaching full-time she created a garden from a wasteland, grew and bottled fruits and vegetables, made jams, jellies and marmalade, cooked, washed, decorated the house, sewed clothes for me and my sister and took us on camping trips to Greece and Turkey in the days when the road was a cart-track. In retirement she made world-wide friends through University Women, travelled, researched local history and became an accomplished watercolourist. My grandmother was formidable too. Left a widow with children of six and four she took over the running of a Wigan pub.

As a young wife I tried to emulate my mother, doing all the things she did. With four children this wasn’t easy and I became very depressed. It was wonderful for me when, in my mid Thirties, I began to write and have poems published, something I had always wanted. Seamus Heaney compares his poetic process to digging. Mine is very like making Crab Apple jelly. My poems nearly always go through a process of being a horrible mess – rather like that bag of apple pulp. I work and work on them until, somehow, like the process of extracting the apple juice and boiling it up with sugar, they undergo a transformation. The final lines of ‘Crab Apple Jelly’ – ‘Oh, Mummy, it was as clear and shining as stained glass and the colour of fire’ – celebrates both my mother’s triumph in making the jelly and mine in completing the poem.

It’s wonderful for me that I have three daughters who have inherited the creativity and capacity for hard work that passed from my mother to me. Emily, as illustrated by her beautiful lino-cut, is an artist. Jane, the eldest, is a novelist and Jessica, the youngest, is a cellist.”

Because it hybridises easily with other apples, pure European Crab Apple Malus sylvestris is becoming a rarer sight in the British countryside. It has also been impacted by farming practices, and many of the ornamental crab apples grown in gardens are other imported species.

Sadly, fewer people today entertain the palaver involved in making Crab Apple jelly, so memories of mothers with the clear, colourful jelly may fade.

“Every year you said it wasn’t worth the trouble – you’d better things to do with your time”

However, the European Crab Apple standing solitary in our countryside has precious ecological, landscape, aesthetic and heritage value that warrants mothering.

Crab Apple Jelly – the print

Commissioned by Apples & People, Emily Feaver describes her printing process:

Firstly, I tracked down a jar of Crab Apple jelly from my local WI market. I made drawings of the jar and wasps and a preliminary watercolour, working out a composition and deciding on how many colours I would use.

Each colour would require a separate Linocut block using water based inks. I usually start with the black layer ; the bold back outline and details. Once that is cut and printed I can use tracing paper to transfer the image to separate, identically sized Lino blocks, which are then cut to take each separate colour, in this case a grey, a purple, a yellow and red. Rough prints are made on cheap paper as I go along to see how it is progressing.

After much fiddling and recutting the final Lino blocks are ready to print on good paper. There are various methods of printing, the usual one being with a printing press and Ternes Burton registration pins to key the print, but I print all my work by hand, using a spoon (another parallel with my jelly-making grandmother). I use fixed lines drawn on a card base and the back of my print to help key my print by ‘eye’ which for me is immediate and unfussy, but requires a very steady hand. Each colour is printed separately allowing some time to dry before the final black layer is printed.

Sources:

- Feaver (1994) The Handless Maiden

- Juniper and Mabberley (2019) The Extraordinary Story of the Apple

- Morgan and Richards (2002) The New Book of Apples

- Worrell, Ruhsam and Renny (2021) Discovering Britain’s Truly Wild Apples in British Wildlife February 2021

Thanks to:

- Vicki Feaver

- Emily Feaver

- Dr Markus Ruhsam, Molecular Ecologist, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

- Abigail McKern

- Genie Turton

- Rick Worrell, Forestry Consultant

Concept art of Johnny Appleseed planting a tree for Walt Disney’s animated short Johnny Appleseed (1948) © 1948 Disney

Concept art of Johnny Appleseed planting a tree for Walt Disney’s animated short Johnny Appleseed (1948) © 1948 Disney Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Apple Harvest, Éragny, 1888, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Apple Harvest, Éragny, 1888, oil on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art