Pacific Crabapple: Food, Tools, Medicine and Magic

First Nations Peoples of Canada have used crabapples for centuries. The Gitga’at people call the apples moolks and the trees sgәn-moolks.

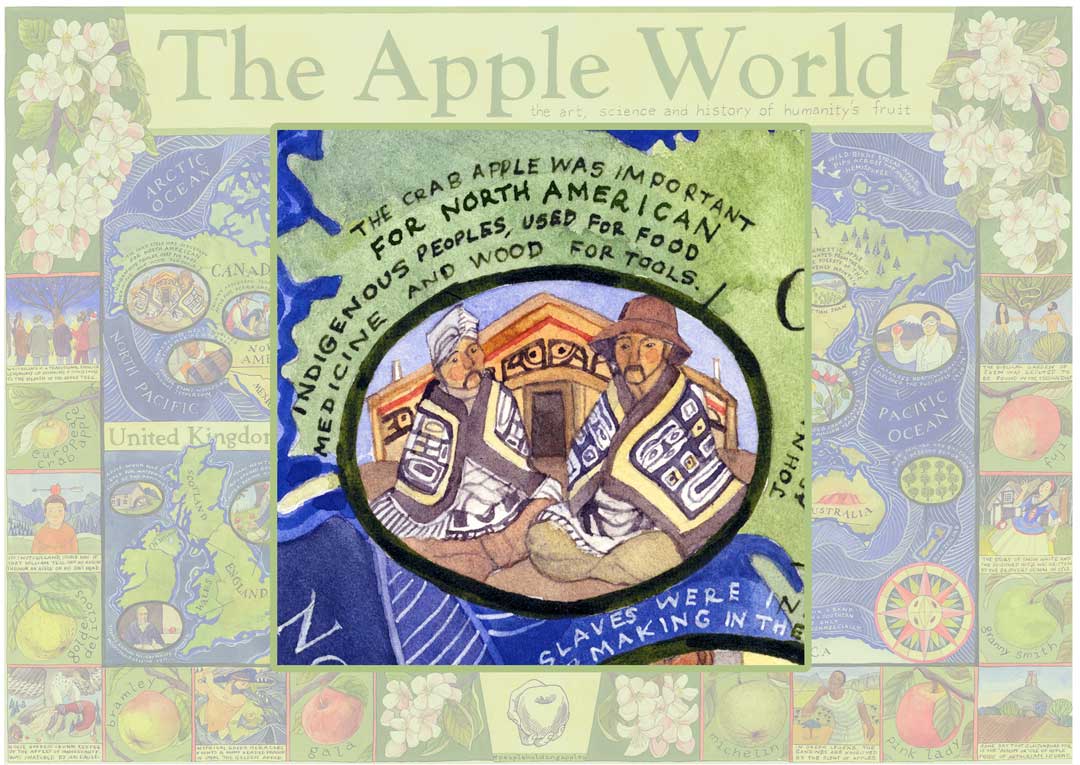

Crabapple trees have grown in North America for thousands of years, the trees and their fruits are significant in the life of Indigenous Peoples, as sources for food, tools, and medicine, and are frequently mentioned in traditional narratives. Published in November 1862, American naturalist and philosopher David Thoreau’s essay ‘Wild Apples’ describes the “native and aboriginal crab-apple…indigenous, like the Indians”. Four crabapple species grow in North America. The Pacific crabapple, Malus fusca, grows on the western coast and has more genetic similarity to the wild apples of China than to the other American crabapples that grow in the east, suggesting spread of Malus fusca across a land corridor from origins in China.

Malus fusca is a small often multi-trunked tree, growing in river valleys, on lake edges and in wet meadows, with small oblong clustered yellow/red fruit.

More than thirty First Nation language groups live on the Pacific West Coast of Canada and USA, where Malus fusca grows wild, each with its own names for this tree and its fruit. The Gitga’at Ts’msyen people call the apples moolks and the trees sgәn-moolks. The Haida call them k’ay (related to the word for “sour”); and Kwakwak’wakw call them tsəlxw, and the trees tsәlxwm’əs. Despite evidence that Malus fusca has low genetic variation across its range, Indigenous People recognise differences in taste, colour, and fruit shape, among different crabapple populations. Traditionally, families have inherited responsibility for tending and harvesting the fruit of specific trees in the wild or around camps and settlements. There is also evidence of historic “forest gardens,” where crab apples and other culturally important plants were planted and managed within forest settings. Smaller, longer stemmed, sweet varieties called gasasii (“long-legs”) by Gitga’at people are particularly prized. Harvesting was traditionally overseen by the chiefs who would pronounce when the fruit was ripe.

Ła Łaayas No’oh is a very important orchard to the Gitga’at, situated in a watershed where the Gitga’at have lived for over 10,000 years. It is stewarded by a specific chiefly name that is inherited through matrilineal descent. The name holder takes care of the orchard and disperses fruit amongst the community. Being one of the larger, more productive, wild fruits found in the area, crab apples have long been an important food. They are generally cooked lightly, then preserved whole in water or fish oil from eulachon, a small smelt, traditionally stored in bentwood boxes of western redcedar.

Crabapples have been a highly prestigious food for Northwest Coast First Peoples, still used today in feasts and in everyday meals

Preserved crabapples were customarily cooked, whipped with eulachon grease, and eaten as a dessert. They are still to this day an important winter feast and ceremonial food. One Kwakwaka’wakw dowry for a wedding was said to include ten large cedar boxes of preserved crabapples and five boxes of oil to put on them for serving. More recently, people cook and freeze the crabapples or make them into jams and preserves.

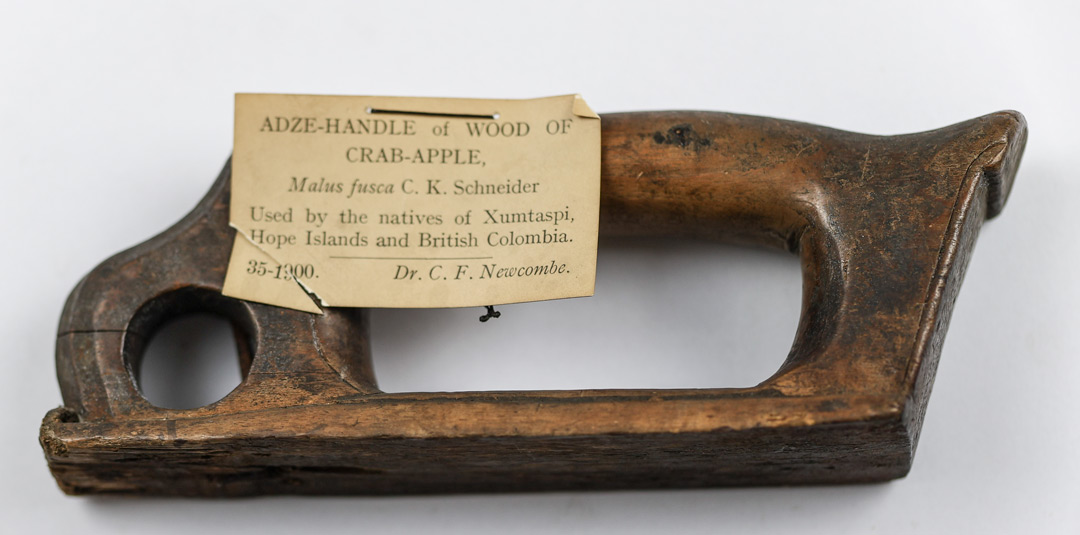

Crabapple wood is tough and hard and, being readily available, the wood has for centuries been used for tools, such as handles for axes and adzes, and for digging sticks and mauls, as well as for making various types of fishing equipment from fishing floats and hooks, harpoon shafts and paddles, to salmon spreaders for smoking or barbecuing. Crabapple wood gambling sticks are sometimes used in traditional games such as Lahal, an ancient game, where a player of one team guesses which of his opponents’ hands holds the unmarked stick. Other sticks are used for scoring.

Crabapple was also important as a source of medicine

Indigenous tribes used different parts of the tree medicinally. Most commonly, bark from the trunk or branches was prepared either as a tea or decoction, or juice was scraped from the bark. Applications ranged from treatment for skin troubles to use for many internal ailments from coughs to diarrhoea.

The entire tree was also used as a spiritual ‘medicine’ by different tribes: A cloth with spit-up blood was placed in a crack in the tree and allowed to grow over making the disease disappear; for skin troubles like eczema, the skin was rubbed with four different cloths that were each placed in a different crack in the tree; a child’s afterbirth was tied to a young crabapple tree in the belief that the child would grow up to be strong like this tree; a girl at puberty or a woman in mourning was rubbed with soft cedar bark, which was then wedged into the cleft of a crabapple tree to make her strong and enduring.

Crabapples have a special place in the oral histories of the coastal Indigenous Peoples; they are the most mentioned fruit in traditional stories of the coast, and the trees were often given human traits.

In ancient times, the trees were thought to have been human beings transformed but retaining their human souls.

For some, crabapples were human eyes in the Land of the Dead. The Gitga’at refer to the apple’s calyx as its t’i’ik or belly button.

Crabapple trees could also offer protection, with the Kwakwak’wakw telling a story about a group of people, escaping monsters, who threw a comb behind them that grew into a thicket of crabapple trees.

As food, tools, medicine and magic, the First Nations Peoples cherish the Pacific crabapple. Much can be learned from their respect for this small, tart apple and nature’s other bounties.

Sources:

- Armstrong et al. (2021) Historical Indigenous Land-Use Explains Plant Functional Trait Diversity in Ecology and Society

- Kuhnlein and Turner (2020) Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Nutrition, Botany and Use

- Routson et al. (2012) Genetic Variation and Distribution of Pacific Crabapple in Journal of The American Society for Horticultural Science

- Turner and Bell (1973) The Ethnobotany of the Southern Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia in Economic Botany

- Turner (2021) Plants of the Haida Gwaii. Xaadaa Gwaay guud gina k’aws (Skidegate), Xaadaa Gwaayee guu giin k’aws (Massett)

- Wyllie de Echeverria (2010) Moolks (Pacific crabapple, Malus fusca) on the North Coast of British Columbia: Knowledge and Meaning in Gitga’at Culture. Unpublished MSc. thesis, University of Victoria, BC

Thanks to:

- La’goot Spencer Greening, Gitga’at Nation and Ph.D. Candidate, Simon Fraser University, BC

- Dr Nancy Turner, Emeritus Professor, Environmental Studies, University of Victoria

- Victoria Rawn Wyllie de Echeverria, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, UK

- Ben Hill, Collections Manager, Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Ford Maddox Brown - Tell's Son 1880 Private Collection - Bridgeman Images

Ford Maddox Brown - Tell's Son 1880 Private Collection - Bridgeman Images JJ Lankes

JJ Lankes