Imitation Apples

Apples have been modelled for centuries – for education, aesthetic, and sharing

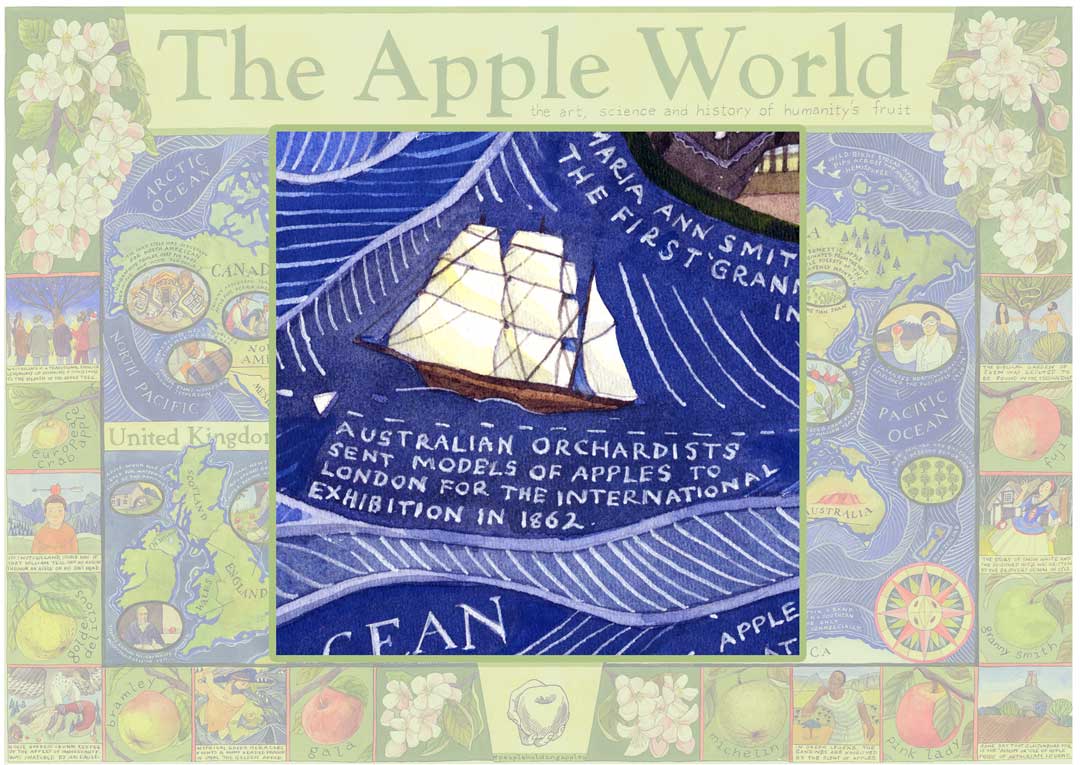

The International Exhibition, which opened in London at the beginning of May 1862, comprised a vast array of exhibits showcasing industrial and agricultural developments around the British Empire and beyond. The Spectator newspaper reported on 3rd May 1862 that the Exhibition opened “with as much of pomp as a nation…could contrive to display” at a time of tensions around the world and economic crisis at home. Queen Victoria did not attend, still being in mourning after the death of her husband Albert who had organised the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace a decade earlier. The Exhibition included large displays of exquisite model apples shipped from Australia to reveal the horticultural prowess of the young colony.

Apples have been modelled since ancient times – a way of preserving them to study and appreciate beyond their natural season, without the risk of decay.

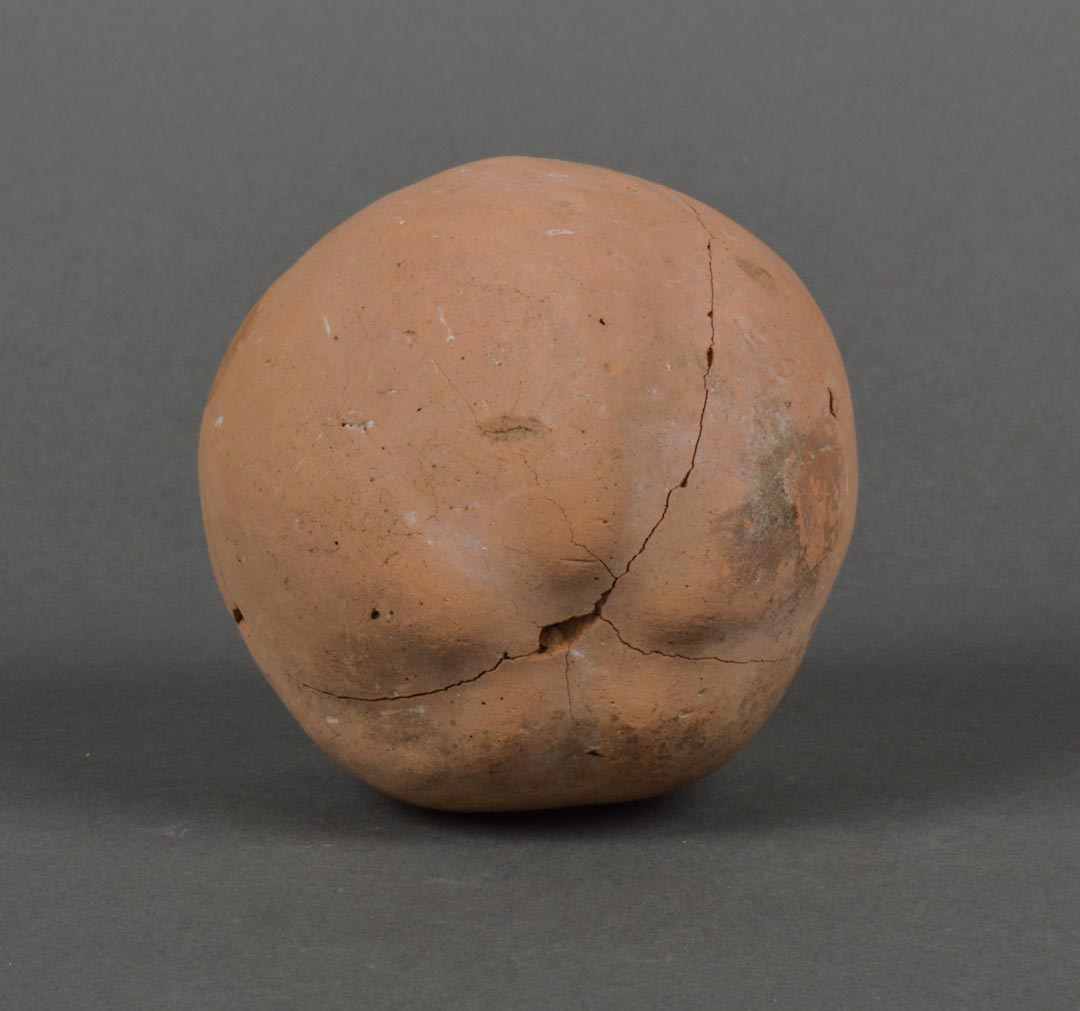

As early as the fifth century BC, small to life-size terracotta model apples were sculpted by the Ancient Greeks. Such models may have been associated with Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and fertility, possibly votive offerings or other tokens to encourage a fruitful marriage or ward off discord. Over the next thousand years, modelled fruit were made in terracotta, marble, glass, and plaster as table decorations for the wealthy, including royalty across Europe. Later, as techniques developed in the first half of the seventeenth century, models could be produced with more precision by casting in wax from moulds taken of the real fruit.

This happened particularly in central Germany and northern Italy. These painted true-to-life models could be displayed in special cabinets or amongst real fruit to confuse the senses of dinner guests. In Die Kunst der Wachsarbeit, an 1837 book on how make wax models, Austrian Josef Meisl writes that “if they are mixed with real ones, they are not easily recognisable as imitations until someone tries to eat them.” Furthermore, prospective produce could be demonstrated to customers – as Francesco Garnier Valletti (1808-1889) did in the 1850s, producing fruit and vegetable models to advertise, year-round, the plants of Turin nurseries for French entrepreneur Auguste Burdin and others – effectively a three-dimensional sales catalogue.

“Frutti modellati cosi vivamente dal vero da scambiarli coi naturali”

Francesco Valletti 1846

To make models, shaped from life, that are indistinguishable from the natural fruit, Valletti developed a sophisticated ceroplastic substance for casting, the recipe for which includes alabaster, wax, honey and tree resin.

His perfect models still exist today in the Museo della Frutta in Turin, which holds 286 apple models amongst its vast collection of Valletti’s work.

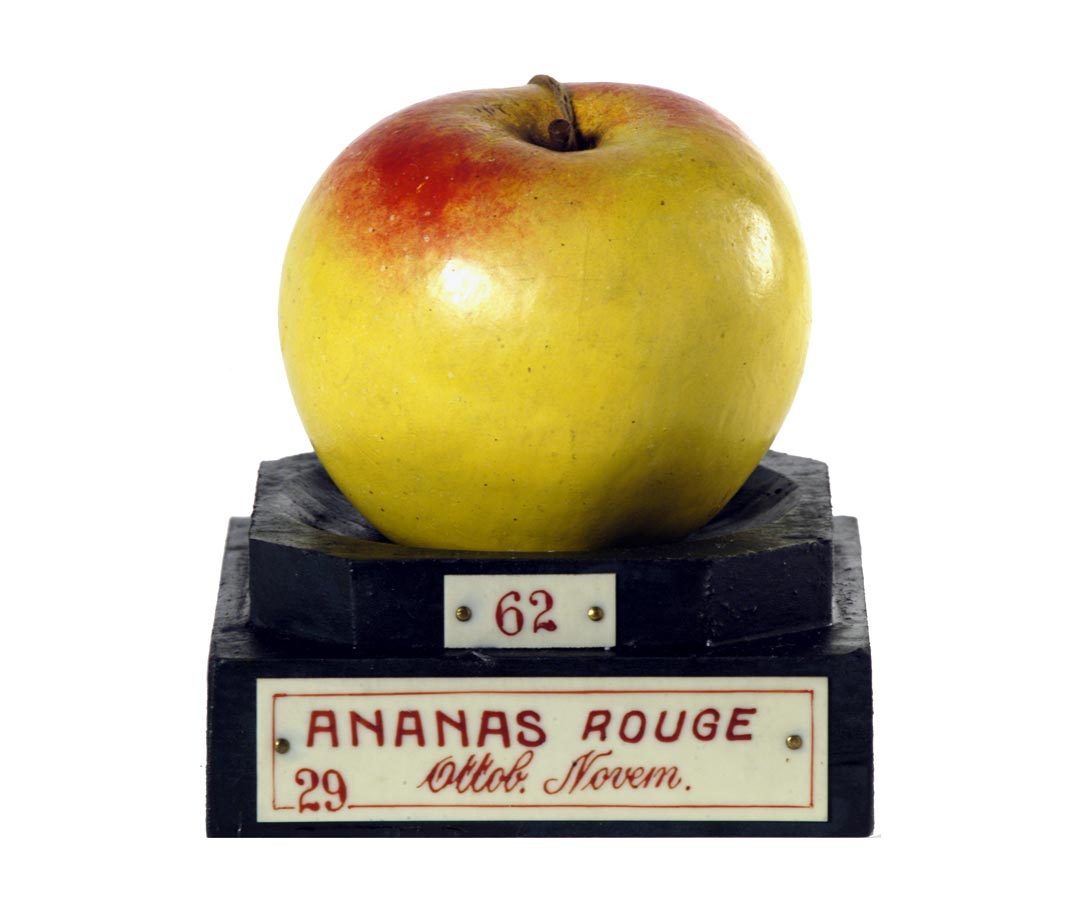

Later, in Germany, papier mâché was perfected as a less breakable substance with surfaces that enabled finer painting. Preeminent amongst the German fruit modellers was Heinrich Arnoldi (1813-1882) in Bavaria who used a form of papier mâché called compositions-masse which drew on his family’s experience of porcelain manufacture.

With German biologists leading the world at the time, Germany became the centre of modelling to aid interpretation of the natural world, and teaching. Arnoldi sold models worldwide in the second half of the nineteenth century.

“Transforming the natural realm into a controlled and domesticated artificial kingdom, such scientific simulacra represented the triumph of form over matter and industry over nature.”

Jan Brazier and Molly Duggins

The Santos Museum in Adelaide Australia has one of the most complete Arnoldi sets, comprising 192 apples that were growing in Germany 150 years ago. They were acquired to demonstrate how apples ought to grow in South Australia and to help correctly name varieties.

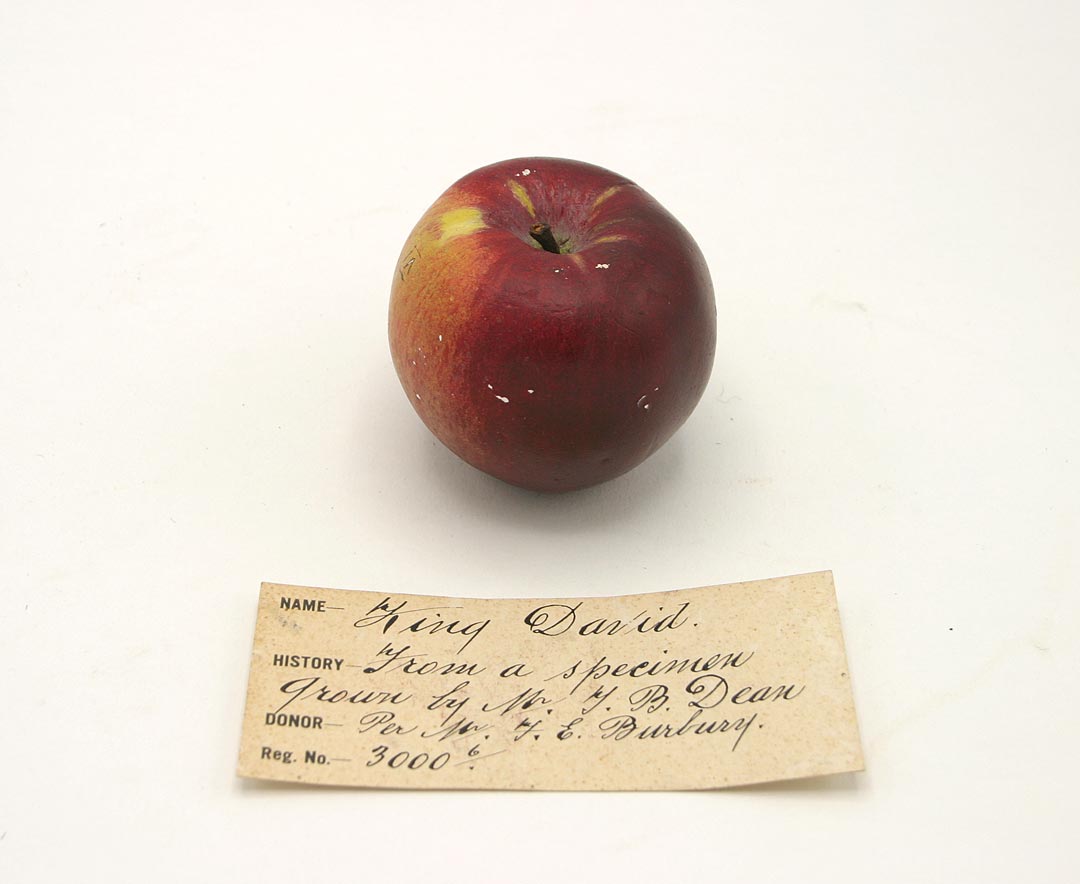

Elsewhere in Australia, the museum at Melbourne itself employed skilled craftsmen who were supplied with apples by the Department of Agriculture and painstakingly recorded new varieties of apple, and other fruits and vegetables.

Two wax models were made of each specimen, one to return to the government as a reference for growers and one for the museum’s collection. In this respect, the museums at the time took on an important and active recording role as well as being educators of the public.

Thomas McMillan from Scotland was employed by the Museum from 1872 and was a prolific modeller. Later, his daughter Miss Anna Gillespie McMillan also made fruit models for museums in Melbourne and Sydney.

“As museum artefacts they encapsulate the power of the object, …revealing layer upon layer of interpretation – aesthetic, artistic, scientific, educational, promotional, personal and heritage.”

Liza Dale-Hallett, a former senior curator at Museum Victoria

Each model was handmade. A plaster mould was taken of the real fruit. The mould was cut in half, each filled with wax or papier mâché, then brought back together when dry and covered with a thin layer of plaster which would be painted. Modelling in wax and papier mâché was relatively cheap and allowed multiple copies to be cast from one mould.

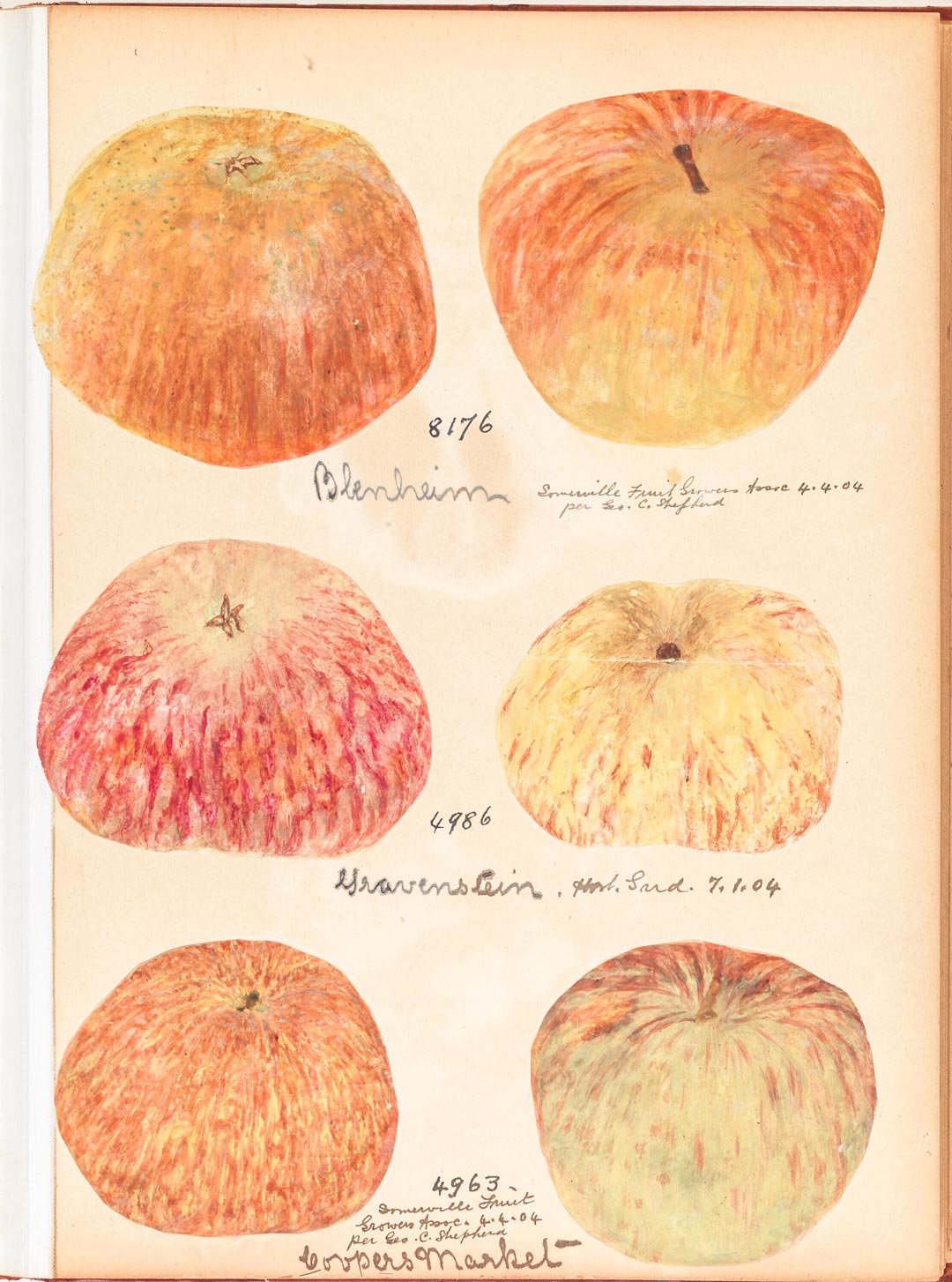

The casts were mostly painted by specialist women artists, each one an individual work of art, portraying the subtle hues and textures of different apple varieties. The talented artists developed special methods to capture the essential characteristics of each fruit, including their blemishes. Artists often recorded the precise colouration of each apple in watercolour albums to reference when they were painting the models, otherwise the models would be left until the following year to be painted when fresh fruit was again available to copy.

Newspapers advertised lessons in making wax fruit from as early as 1851 in Melbourne and in 1860 instruction in the art was offered to “the Ladies of Sydney”.

Beautiful though they are, model fruit collections were not however simply art. They were a scientific tool, enabling the study of how apples fared under different growing conditions and methods, healthy or diseased. They can provide a more complete record than even the best horticultural painting. The apples formed a reference library which could be studied out of season and collections at Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Hobart were referred to by fruit growers. In this way, the models promote horticultural prowess.

As described in an 1878 press review of Melbourne Museum “The collection of fruits, modelled in wax, is growing fast. The system adopted is to copy in wax every fruit that can establish its claim to novelty or exceptional excellence, and in this way a collection has been got together by means of which the claims of new pretenders to fame can be accurately weighed…The fruit models in the museum are beautifully and faithfully executed, and afford a ready means of testing the value of alleged newness or merit in pomology.” The Australian 23 February 1878.

Melbourne Museum now holds 588 models of 321 apple varieties, mostly made between 1873 and 1949.

Whilst there were some modellers in the UK in the nineteenth century, such as Mr H Hervey Andrews of Reading and the Mintorn family in London, models are more closely associated with the teaching techniques of German institutes and the colonies rather than British universities where paper, and therefore drawing, prevailed.

However, England was treated to a large display of model apples in the International Exhibition of 1862, when the Australian states of Victoria and Tasmania included them in the artefacts that they sent to London to display. By using models, apples could be sent on the long voyage from Australia to England and still be displayed in perfect condition throughout the six months of the Exhibition, despite some concern at the time “that the injurious effects of a sea voyage will defeat the attempt to give a fair representation of their colour.”

These models were designed to demonstrate the suitability of Australia for growing English fruit – and indeed their superiority. A report on the Tasmanian products at the Exhibition boasts, “All the sorts described in English Catalogues as ‘below medium’ size, have grown far above ‘medium’; and those so described as ‘medium’ here attain the catalogue designation of ‘very large’.” Being perfect facsimiles as regards shape and size, “The models exhibited of the different Tasmanian Apples in wax will afford Horticulturists the means of satisfying themselves on this point.”

The exhibited models were produced by various artists. For example, the models from Tasmania appear to have been made by Mrs and Miss Luckman of Collins Street in Hobart Town. Together, their models become a feast for the eyes.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Australian model apples were displayed in exhibitions across the world – from America to India. Such exhibitions were a means to secure export markets for natural resources, crops, and finished goods. They also served to inform prospective emigrants of opportunities Australia could offer.

The collections show the wide biological diversity of apples in the past in three-dimensional form. As such they form an invaluable aid to identifying historic varieties and to observe their transformation over time. Those apple varieties that have since disappeared are also a lesson in the transient nature of apple cultivars – unless they are preserved by the human intervention of grafting.

For example, Melbourne Museum has a wax model of a seedling raised by Robert Whatmough in Greensborough and modelled by Thomas McMillan at Melbourne Museum in 1875. Greenborough is now a suburb of Melbourne and Whatmough’s Winter Pippin appears to be lost – as do many other varieties modelled in nineteenth century Australia.

The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery no longer holds a collection of models, although their records show some forty wax apples and pears were produced by a Mrs Jhonson (sic) for the Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1866-67 and these award-winning models were presented to the museum afterwards. A small collection of later apple models is held by The Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston, Northern Tasmania.

Only with the advent of good quality colour photography and technologies to allow long term storage of fresh produce has large scale modelling become obsolete. However, some specialists continue to ply the skill. The family firm of SOMSO Modelle was founded in 1876 and, now with the fifth generation involved in the firm, continues to make a wide range of models in Coburg, Germany. SOMSO is probably the only commercial manufacturer of fruit models using traditional processes. Their sales catalogue includes 215 different apple models.

“Unser Vorbild ist die Natur”

SOMSO Modelle

“Nature is our Model” exclaims SOMSO’s slogan. Modellers have encapsulated apples, from nature, at points of time in history. Not only have they bequeathed these beautiful works of art but their models supported horticultural development around the world. Today they also demonstrate each apple variety’s sometimes transient existence.

Afterword

After the 1862 International Exhibition, the Australian States of Victoria and Tasmania gifted their model apples to the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. These form part of Kew’s collection of model apples that is being loaned to the Museum of Cider in Hereford, where they will be displayed from 27th October 2023 to 28th January 2024. This will be the first time that these models have been shown in their entirety for fifty years, and they have never before been exhibited together outside London.

With many of these models being over 160 years old, it is not certain that the apples in Kew’s collection are all correctly recorded. Therefore, whilst exhibited in Hereford, it is hoped that apple enthusiasts will come to help check the varieties.

The Museum of Cider has also commissioned artist Lottie Sweeney to make a new collection of model apples for Apples & People. This comprises the most significant apple varieties existing today, as judged by apple experts around the world. Lottie casts her models from nature using polyurethane resin in silicone moulds.

Sources:

- Brazier and Duggins (2015) Visualising nature: Models and wall charts for teaching biology in Australia and New Zealand

- Christiansen (2016) Making the connection between history, agricultural diversity and place – the story of Victorian apples. PhD thesis

- Costanzo (2007 ) Francesco Garnier Valletti in Jalla (ed) Museo della Frutta Francesco Garnier Valletti Torino

- Dale The Wonders of Wax in Rasmussen (2001) A Museum for the People

- Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia 1866-67 Official Record

- Kanellos (2013) Imitation of life: a visual catalogue of the 19th century fruit models at the Santos Museum of Economic Botany in the Adelaide Botanic Garden

Klinger (2021) The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: Miscellaneous Finds of Terracotta - Lechtreck (2003) A history of some fruit models in wax and other materials: scientific teaching aids and courtly table decorations in Archives of Natural History Volume 30 Part 2

- Mercury newspaper article (1861) The International Exhibition

- Spectator newspaper article (1862)

- Valletti (1846) Raccolta di ogni sorta di segreti. Collection of all sorts of secrets. Handwritten work

- Whiting (1862) The Products and Resources of Tasmania as illustrated in the International Exhibition 1862

Thanks to:

- Jan Brazier, Curator History, Macleay Collections, University of Sydney, Australia

- Rebecca Carland, Senior Curator History of Collections, Society and Technology, Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

- Dr Caroline Cornish, Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London

- Paola Costanzo, Curatrice collezioni, Museo della Frutta “Francesco Garnier Valletti”, Torino

- Peter John Higgs, Curator, Greek Collections, British Museum, London

- Joanne Huxley, Research Officer, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania

- Dr Stelios Ieremias, Directorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, Hellenic Ministry of Culture

- Tony Kanellos, Senior Curator, History Trust of South Australia

- Burcu Keane, Assistant Curator Public History, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania

- Dr Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck

- Dr Sonia Klinger, Senior Lecturer, Department of Art History, University of Haifa

- Lindl Lawton, Manager Interpretation and Cultural Collections, Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, Australia

- Erin Messenger, Economic Botany Collections Manager, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, London

- Dr Mark Nesbitt, Senior Research Leader, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, London

- John Pinniger, Heritage Fruits Society, Melbourne. Victoria, Australia

- Katrina Ross, Historical Collections Coordinator, Library and Cultural Collections, University of Tasmania

- Hans Sommer, Managing Director, Marcus Sommer SOMSO MODELLE, Coburg, Germany

- Lottie Sweeney, special effects painter and maker

- Matilda Vaughan, Curator Engineering, Society and Technology, Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

Rob Janoff Designer of the iconic Apple Computer logo Courtesy of Rob Janoff Agency

Rob Janoff Designer of the iconic Apple Computer logo Courtesy of Rob Janoff Agency Isaac Oliver -An Unknown Girl, aged four 1590 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Isaac Oliver -An Unknown Girl, aged four 1590 © Victoria and Albert Museum