Wilding Apples

Of The Camborne & Redruth Mining District by William Arnold

William Arnold describes his work with apples in an historic mining landscape in Cornwall in South West England, industry that was operating at its peak in John Chapman’s lifetime. Just like the Appleseed nurseries on the edge of the American wilderness, pips from discarded apples in Cornwall have grown to produce a diverse array of ‘wilding’ apples.

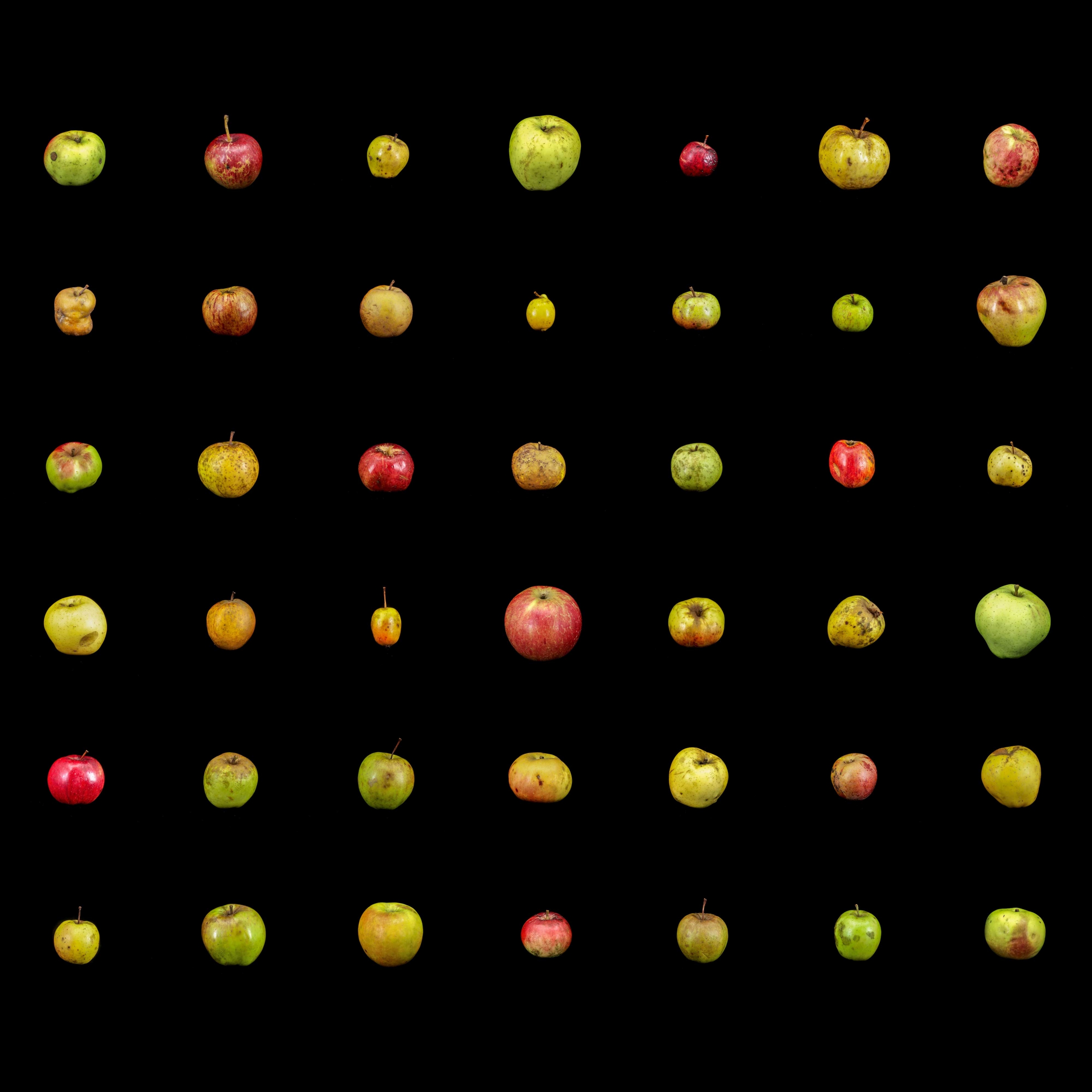

William’s article and his composite photograph ‘Wilding Apples of The Camborne & Redruth Mining District’ was commissioned by Apples & People as an English appreciation of wildings like those propagated by Johnny Appleseed.

The last three years I have been involved with a project called ‘Some Interesting Apples’, the primary aim of which is to record and, where characteristics make desirable (and sometimes where they don’t), preserve wilding apples, i.e., domestic apples growing on their own roots as the result of a discarded core.

I have been fascinated by these trees for as long as I can remember, hooked on the narrative of the discarded core, seemingly against the odds germinating seeds by the side of the road to create wonderful free fruit. I couldn’t understand the disinterest of others – the waste.

As a reasonably guilt-free discard from a car or train window these feral seedlings of domestic apples proliferate, perhaps catching our eye in a flash of May blossom or viewed laden with fruit by a stretch of railway track on a drab October schedule delay. Piles of smashed fruit on an early winter commute and late hangers-on – an inconvenient genetic trait for commercial cider making – presenting as holiday baubles in the gloom.

This project has received public donations of fruit from as far away as Canterbury and Leeds though primarily it has focussed on central and west Cornwall, where I have worked with fellow artist and apple enthusiast James Fergusson to map and photographically record as many wilding apples as possible. Between the two of us and with a little help from others we have recorded over 330 trees and therefore over 330 novel varieties of apple. Many of these have been subject to public taste trials and the fruit all recorded as part of a photographic typology, of which the composite photograph of wildings from the Camborne Redruth mining district is part.

“Every wild-apple shrub excites our expectation thus, somewhat as every wild child. It is, perhaps, a prince in disguise. What a lesson to man! So are human beings, referred to the highest standard, the celestial fruit which they suggest and aspire to bear, browsed on by fate; and only the most persistent and strongest genius defends itself and prevails, sends a tender scion upward at last, and drops its perfect fruit on the ungrateful earth. Poets and philosophers and statesmen thus spring up in the country pastures, and outlast the hosts of unoriginal men.”

Henry David Thoreau (1862)

Pioneers

The domestic apple growing wild on its own roots is an escapee, a neophyte non-native often germinating on waste ground and wayside where cores are casually tossed. Two of the biggest populations found during this project have been on the dune system of a popular holiday park at Par Sands and throughout the complex of former tramways turned recreational heritage paths of the Camborne & Redruth UNESCO World Heritage mining landscape.

The latter location has an extraordinary population ranging from the crabbiest pippins on tractor flayed bushes to elegant orb-like specimens, grocer’s display ready despite the parent tree receiving no attention at all. The idea that all these apples, representing such huge diversity of colour, shape, and flavour, were the descendants of those eaten by the ordinary men and women who worked this hugely damaged and polluted but recovering landscape was irresistibly romantic.

I expected that I would find numerous records in the major archival store of Cornish historical documents at Kresen Kernow of local orchards supplying the mining communities but other than a few entries from the court records of those poor unfortunates caught and punished for scrumping, apple pickings were slim.

To be fair, I was disabused of my notion that populations of wilding apples would bear any great resemblance to those grown historically in a given area early on in the ‘Some Interesting Apples’ project when I began my research photographing to scale all the apples of Cornish heritage orchards that I could access. While some genetic traits must be inherited, to the casual observer the apples of the hedgerow generally defy categorisation other than the odd supermarket Golden Delicious that hasn’t fallen too far from the tree.

Apples are hardy plants, evolving in isolation in the mountains of the Tian Shan, relatively short-lived as individuals and with a seemingly scattergun approach to evolution – make enough offspring and at least one or two will stick in the local environment. It leads one to wonder whether this hugely heterozygous, promiscuous, and short-lived nature makes the apple potentially useful within robust novel ecosystems in the context of a rapidly changing climate.

The highest diversity of Cornish apples I have ever seen is to be found not in the wonderful Mother Orchard at Cotehele but next to spoil heaps and by the sides of the mineral tramways of Camborne and Redruth.

Look around you anywhere in this environ and the evidence of past extractive industry is plain to see. Rusting iron-red toxic lagoons, spoil heaps where a hundred years after the last ore was raised only rare bryophytes and liverworts grow, and of course that icon of Cornwall, the engine house with its slender chimney standing sentinel in the scores of picturesque ruins – on hills, rugged cliff, and valley, doing fine service for the tourist board where a perfect Instagram sunset can be captured just so in the sturdy arched windows.

With UNESCO World Heritage status, the Camborne and Redruth mining district is proud of its place as the centre of origin of modern world mining.

Soviet-era botanist Nikolai Vavilov, who dedicated his life to finding the biological origins of major food plants to combat hunger, theorised that the “centres of origin” of a species can be found in the places where you find the highest diversity of that species.

The highest diversity of apple occurs in the remnants of the wild fruit forests of the Tian Shan in Southern Kazakhstan and Vavilov thus concluded that the domestic apple had evolved from these wild apples, primarily a strain called Malus sieversii. Modern genetics proves Vavilov right.

This waste ground population is obviously not the modern apple’s centre of origin, it is there because at some point someone threw the remnants of their healthy snack in the hedge, or an animal did its business, but it does represent a remarkable accumulation of genetic diversity in a small area. It has led me to think of the domestic apple in its feral form not as a cosseted plant of cultivation but a pioneer species taking its chances amongst the willow, bramble and rosebay. The forty-two apples presented here represent just a snapshot of this diversity.

In his 2015 book The New Wild, environmental journalist Fred Pearce makes the controversial claim that invasive and non-natives “will be nature’s salvation”, that environmental orthodoxy has it all wrong and we’re wasting our time uprooting and trapping to preserve a mythical pristine. He probably overeggs the pudding, perhaps dangerously so; gamely looking to find upsides to Kudzu and Japanese Knotweed and he cherry-picks certain human introduced non-natives which have proved themselves useful, such as the honeybee and earthworm in North America, to make a point for a laissez-faire approach to conservation.

However, on some level in certain circumstances, perhaps there is something there. A much-made argument in Pearce’s book goes along the lines of non-native species often being well equipped to take over and rewild land despoiled by human action…it is a seductive narrative. During my time collecting feral apples for this project I have unsurprisingly found the greatest concentrations in places with the greatest movements of people – road and wayside but what surprised me most was how some of these concentrations were in quite marginal and degraded landscapes. One specimen for example w3w///fearfully.notifying.positions clings on fruitfully to the side of Carn Brea, a mine-shaft riddled hill at 700 feet.

I have started to think of the feral domestic apple in this context, as a highly useful non-native. Not exactly invasive, as far as I am aware it is not crowding out any native species and provides much support for a diverse ecosystem, but it is certainly prolific. Its only shortcoming seems to be that it is neither from the knowable controlled and tasteful world of the orchard nor is it the quasi-mythical, rare, thorned, native, and truly wild Malus sylvestris.

Research grants are awarded and newspaper column inches devoted to celebrating the discovery of a lone pure-bred crab apple clinging to a crag on an uninhabited Hebridean Isle but where is the wonder at a theoretically infinite variety of accidental seed-grown fruit each with the potential to be propagated, registered, and like a comet given the finder’s name all while supporting a diverse number of other species?

This seedling diversity and the potential for extraordinary apples to emerge from an essentially random selection of waifs and strays also puts me in mind of human pioneer, John – Johnny Appleseed – Chapman, who did much for the 19th century westward expansion of the apple in the USA and who remains a notable figure within foundation myths of the modern United States.

Always one step ahead of the homesteaders, Chapman, out of either religious conviction that grafting was adulterous to the work of God or canny business practice, grew apples from seed only. This legacy of thousands of novel varieties, recently brought to widespread attention by the collection and conservation work of Matt Kaminsky AKA Gnarly Pippins, can still be found in the relict orchards and scrubland wildings of what was once the western frontier of European expansion in the US.

“Through the whole growing season, the supermarket shelves of the world display for good commercial reasons probably fewer than fifty apple cultivars. Yet in the orchards of abandoned homesteads in upper New York state, along the ancient trackways of England, and in thickets and on cliff slopes and other marginal land in the whole of the temperate world, seedling apples of unknown parentage constantly arise. Most of these are of little value except for pig food or rough cider, but here and there a rare elite individual will emerge.”

Barry Juniper (2019)

Some of the most celebrated American cultivars including McIntosh and Golden Delicious and England’s own famous Bramley’s Seedling occurred as chance specimens, with every one of those apples we eat today descended from clones of an original tree.

In Almaty, Kazakhstan, Juniper & Mabberly note that such is the diversity of apples grown on their own roots, it is not uncommon to find large, sweet seed-grown apples for sale in the markets and roadside stalls. It is simply often not worth the hassle to graft an orchard with known cultivars. One can only wonder at the diversity of flavour!

In photographing these forty-two apples at comparative scale – itself a mere snapshot of a local population – there is of course representation only of colour and form, it says nothing of the taste of these fruit. Through public taste trials held each autumn at Kestle Barton Rural Arts Centre, ‘Some Interesting Apples’ is beginning to gain an impression of the diversity of flavour and potential usefulness for human consumption, or otherwise!

In the wild fruit forests of the Heavenly Mountains, no two apples taste exactly the same but much the same can be said for the road and wayside wildings of Camborne and Redruth, or anywhere else.

Sources:

- Henry David Thoreau, Wild Apples, The Atlantic Magazine, November 1862

- National Trust – Cotehele’s Mother Orchard – accessed 01/03/22

- Pearce, F., The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature’s Salvation Beacon, London, 2015.

- Los Angeles Review of Books – accessed 01/03/22

- what3words mapping app – used to give locations and names for apple trees recorded for the ‘Some Interesting Apples’ project

- The Independent – accessed 01/03/22

- The Boston Globe – accessed 28/02/22

- Juniper, B. & Mabberly, D.J. The Extraordinary Story of The Apple, Kew: London, 2019, p.240

Golden Apples and Strudel

Golden Apples and Strudel Elisabeth Dowle - Newtown Pippin for Morgan and Richards (2002) The New Book of Apples © the artist

Elisabeth Dowle - Newtown Pippin for Morgan and Richards (2002) The New Book of Apples © the artist