Grafting: Giving Nature a Helping Hand

The skill of grafting, to preserve and propagate valued apple varieties, was learnt in ancient times

As people took the domestic apple westwards from the fruit forests of the Tian Shan, early humanity wanted to preserve and propagate apple varieties that they found best suited their needs. This required them to learn from natural occurrences how to graft a scion from a tree that they wanted to propagate onto a healthy rootstock of another.

The skill of grafting passed from one civilisation to the next. There is evidence from Greek and Roman times of the use of grafting and, thanks to the Romans, the practice was widespread across Europe by medieval times.

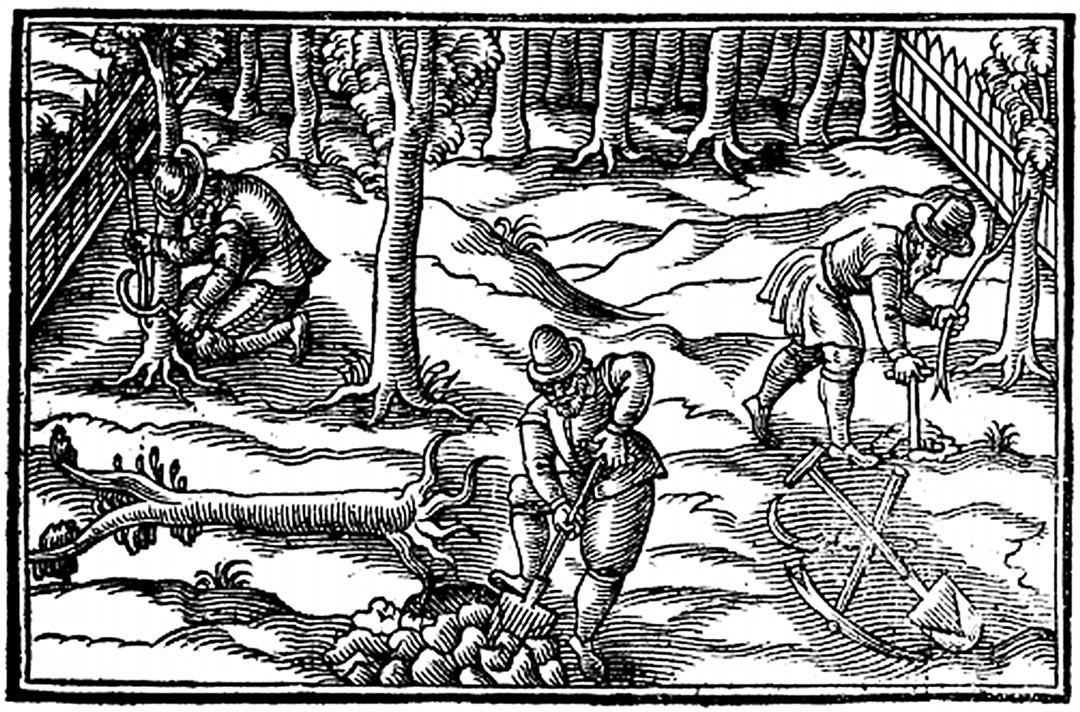

William Lawson was a Yorkshire cleric. His book ‘A New Orchard and Garden’, first published in 1618, describes the act of grafting (formerly ‘graffing’) as it had developed in Jacobean England.

“The reforming of the fruit of one tree with the fruit of another, by an artificial transplacing or transposing of a twig, bud, or leaf, (commonly called a graft) taken from one tree of the same, or some other kind, and placed or put to, or into another tree in one time and manner…

…it is the most known, surest, readiest, and plainest way to have store of good fruit.”

William Lawson

Except for the precise way that it is done, and the use of specialist tape, grafting remains the same today as the only efficient way by which any apple variety (whether a natural pippin from seed, or from commercial cross-breeding) is kept beyond the lifetime of the first tree.

William Lawson explains the process

“It is thus wrought:

You must with a fine, thin, strong and sharp saw, made and armed for that purpose, cut off a foot above the ground, or thereabouts, in a smooth section without a knot, or as near as you can without a knot (for some stocks will be knotty) your stock, set, or plant, being surely stayed with your foot and leg, or otherwise straight across (for the stock may be crooked) and then plane his wound smoothly with a sharp knife.

That done, cleave him cleanly in the middle with a cleaver, and a hammer or mallet, and with a wedge of wood, iron or bone, two handful long at least, put into the middle of that cleft, with the same hammer, make the wound gape a straw breadth wide, into which you must put your grafts.

The graft is a top twig taken from some other tree (for it is folly to put a graft into his own stock) beneath the uppermost (and sometime in need the second) knot, and with a sharp knife fitted in the knot (and some time out of the knot when need is) with shoulders an inch downward, and so put into the stock with some thrusting (but not straining) bark to bark inward.

Let your graft have three or four eyes, for readiness to put forth, and give issue to the sap.

It is not amiss to cut off the top of your graft, and leave it but five or six inches long, because commonly you shall see the tops of long grafts die. The reason is this. The sap in grafting receives a rebuke, and cannot work so strongly presently, and your grafts receive not sap so readily, as the natural branches.

When your grafts are cleanly and closely put in, and your wedge pulled out nimbly, for fear of putting your grafts out of frame, take well-tempered mortar, soundly wrought with chaff or horse dung (for the dung of cattle will grow hard, and strain your grafts) the quantity of a gooses egg, and divide it just, and therewithall, cover your stock, laying the one half on the one side and the other half on the other side of your grafts (for thrusting against your grafts) you move them, and let both your hands thrust at once, and alike, and let your clay be tender, to yield easily; and all, lest you moue your grafts.

The best time of grafting from the time of removing your stock is the next Spring, for that saves a second wound, and a second repulse of sap, if your stock be of sufficient bigness to take a graft from as big as your thumb, to as big as an arm of a man. You may graft less (which I like) and bigger, which I like not so well. The best time of the year is in the last part of February, or in March, or beginning of April, when the sun with his heat begins to make the sap stir more rankly, about the change of moon before you see any great appearance of leaf or flowers but only knots and buds, and before they be proud, though it be sooner.

The grafts may be gathered sooner in February, or any time within a month or two before you graft or upon the same day (which I commend).”

There are numerous versions of grafting – some simple, some intricate – and Lawson describes a type of cleft graft.

The different types of grafts are catalogued in Robert Garner’s classic and comprehensive reference work The Grafter’s Handbook. Garner was chief propagator at East Malling Research Station in Kent and his “clear exposition of this subject” is congratulated in a foreword by Ronald Hatton, the director of East Malling famous for categorising rootstocks. Successful grafting depends upon two essential factors: compatibility between scion and rooted receiving tree; and achieving contact between meristematic tissue in the plant, capable of cell division.

Through learning successful grafting, humanity has preserved varieties of apple beyond the lifetime of an individual tree, intervening with nature to share the most valued apple trees around the world and between generations.

Nurseryman John Worle discussing and demonstrating grafting in an old Herefordshire orchard, filmed by Christopher Preece in April 2022. In this video, John demonstrates traditional cleft grafting as described by William Lawson four hundred years ago. He also talks about some of the best ways to go about grafting with older apple trees that are typically found in old orchards.

Beckets Orchard is a large orchard of old bush cider apple trees, originally planted in the 1930s. This orchard was gifted to the Museum of Cider by Susan Bulmer in 2021.

This film is an Apples & People Commission.

Sources:

- Garner (1947) The Grafter’s Handbook

- Juniper and Mabberley (2019) The Extraordinary Story of the Apple

- Lawson (1631) A New Orchard and Garden

Thanks to:

- Dr Barrie Juniper (1932-2023) who was Emeritus Reader in Plant Sciences, University of Oxford

- John Worle, Nurseryman, retired Area Farms Manager and Nursery Manager at HP Bulmer Limited

- Christopher Preece, Photographer and Film Maker

Henry G Van Deman - Antonovka 1886 U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705

Henry G Van Deman - Antonovka 1886 U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705 Life with more than one Granny - Granny Smith and how her apple made an Australian family

Life with more than one Granny - Granny Smith and how her apple made an Australian family